by Michael Riddick

Download / Preview High-Resolution PDF

A crucifix by Michelangelo brought to Seville in 1597 by the silversmith Juan Bautista Franconio

Carlos Herrero Starkie’s rediscovery of a bronze crucifix by Michelangelo—brought to Seville from Rome in 1597 (‘IOMR cast’)1—brings further credence to the present author’s hypothesis that Michelangelo’s original wax model of a crucifix was once in the workshop of Guglielmo della Porta and that bronze casts made from this model were rare and perhaps undertaken by his workshop assistants.2

The evidence in support of this theory is the discovery of an extraordinarily fine cast of a crucifix of coeval quality to that discussed in-depth by the present author in 2021 and earlier, which belongs to an American private collection (‘American cast’) and whose provenance is traced to Italy (figs. 1, left; 14, right).3 The newly discovered crucifix—now belonging to the Institute of Old Masters Research (IOMR) in the Netherlands (cover, fig. 1, right)—was acquired from a private Spanish collection in Madrid, and prior to this, was in a generational collection in San Sebastian in Northern Spain.4 Informing of its use as a model for all the subsequent examples cast in Spain, is not only its notable quality—requisite to produce those subsequent casts—but also the presence of trace amounts of wax and plaster residue along its surface and crevices, as adjudged in the surface analysis conducted by: Sara Cavero, restorer at the Museo Nacional de Escultura de Valladolid; Rosario Coppel, Renaissance bronze specialist, Starkie, director of IOMR; and Ignacio Montero Ruiz, scientist at the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC).5

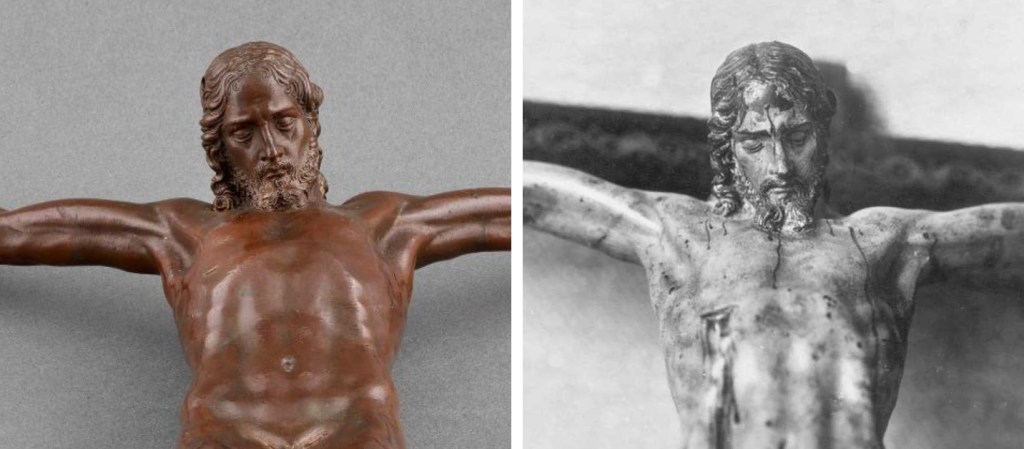

Fig. 1: A bronze crucifix, after a model by Michelangelo, ca. 1538-41 (left; private collection; photo: © GCF); a bronze crucifix, after a model by Michelangelo, ca. 1538-41, documented in Seville 1597 (right; IOMR collection)

The bronze surface of the crucifix had once been entirely coated in wax to protect the metal from the plaster vestment formed over it to produce one or more moulds necessary to make further casts of the sculpture. This coincides with Francisco Pacheco’s claim that casts of a crucifix by Michelangelo—brought to Seville from Rome in 1597—were produced and were painted by Pacheco on and after 17 January 1600.6 Two identified casts are indicative of this record, one in a private collection (figs. 2, right; 4, right; 5, right)7 and another located at the Grand Ducal Palace of Gandia in Spain (‘Gandia cast’) (fig. 3, right).8 Further confirmation of this is found in Pacheco’s notes on how he used an example of this painted crucifix for his canvas painting of Christ on the Cross in 1614-15 (fig. 2, left).9

Fig. 2: Detail of Christ on the Cross painted by Francisco Pacheco, ca. 1614-15, GomezMoreno Museum (left; photo © Fundacion Rodriguez-Acosta); detail of a polychromed bronze crucifix cast by Juan Bautista Franconio, ca. 1597-1600, after a model by Michelangelo and painted by Francisco Pacheco after 17 January 1600 (right; private collection)

Pacheco notes how he later gave Franconio’s example of Michelangelo’s crucifix to Father Pablo Céspedes who is described thereafter as having regularly worn it around his neck. At Cespedes’ death in 1608, his inventory notes a ‘metal Christ without a Cross in a leather case.’ It is believed the cross may have subsequently gone to his friend and assistant, Juan de Peñalosa, and then taken to the Cathedral of Astorga where Peñalosa was appointed as canon. After Peñalosa’s death in 1633, the auction of his belongings included ‘a Christ figure without a cross, very good, in a box.’10 The crucifix must have remained in Spain until its rediscovery in 2023 by Starkie.

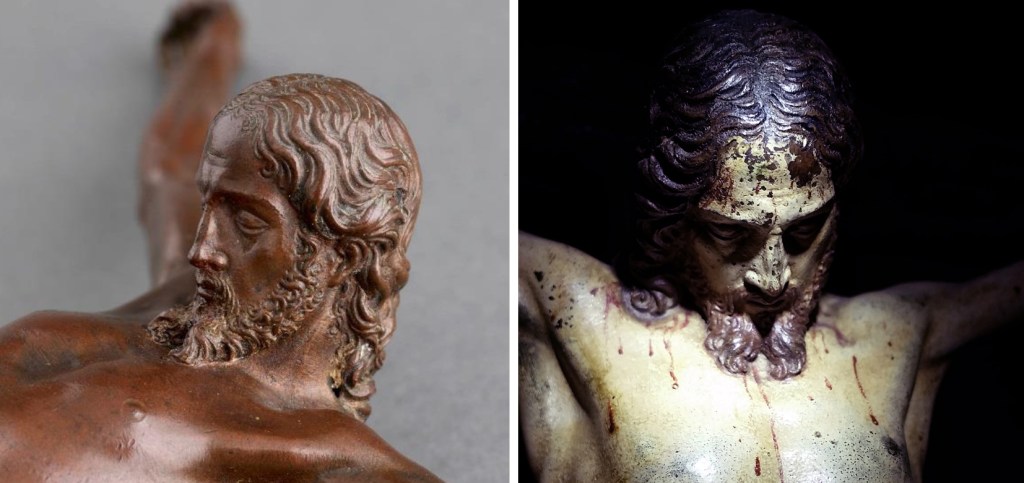

Further encouraging the IOMR cast as the prototype for all subsequent Spanish casts are certain features that immediately relate it to the two aforenoted bronze examples cast in Spain ca. 1597-1600 and painted by Pacheco. There are three features that distinguish the IOMR cast from the other high-quality Roman cast of the crucifix. This regards the feature of a bleeding side-wound on Christ’s torso (fig. 25), the feature of textured eyebrows (fig. 16), the addition of a wrinkle on Christ’s forehead (fig. 5), and a slightly different perizonium (fig. 13). While the texture of Christ’s eyebrows is not readily observable in any of the first-generation of Spanish casts,11 the placement of Christ’s bleeding side-wound is commensurate between the IOMR cast and its feature on the polychrome bronze casts. The wax model or cold-working of the Gandia cast appears to exaggerate this side-wound with a deep impression in the bronze, present in the same location as it is featured on the IOMR cast (fig. 3). Pacheco also appears to reference the placement of this wound on the IOMR cast with his choice location of the painted wound on the other polychrome bronze cast in a private collection (figs. 2, 4), even though there is no integrally cast or cold-worked wound featured on the bronze surface of this cast.

Fig. 3: Detail of a bronze crucifix, after a model by Michelangelo, ca. 1538-41, documented in Seville 1597 (left; IOMR collection); detail of a polychromed bronze crucifix cast by Juan Bautista Franconio, ca. 1597-1600, after a model by Michelangelo and painted by Francisco Pacheco after 17 January 1600 (right; Grand Ducal Palace of Gandia)

Fig. 4: Detail of a bronze crucifix, after a model by Michelangelo, ca. 1538-41, documented in Seville 1597 (left; IOMR collection); detail of a polychromed bronze crucifix cast by Juan Bautista Franconio, ca. 1597-1600, after a model by Michelangelo and painted by Francisco Pacheco after 17 January 1600 (right; private collection)

If the Gandia cast precedes that of the other polychrome cast, it could indicate Franconio made the choice to eliminate adding the side-wound of Christ on subsequent casts of the crucifix, which appears to be the case for two of the three silver casts attributed to him, preserved at the Cathedral of Seville12 and Fundación Pública Andaluza Rodríguez-Acosta in Granada.13 A third silver cast attributed to Franconio is found at the Royal Palace of Madrid14 but requires closer examination to determine if a side-wound is present on that cast.

The distinctive upper wrinkle cold-worked along the forehead of Christ, present on the IOMR cast, is uniquely reproduced on the polychrome bronze cast from a private collection, visible under raking light (fig. 5). This feature is also subtly present on the finest silver cast at the Seville Cathedral and suggests both casts use the IOMR crucifix as their master model.

Fig. 5: Detail of a bronze crucifix, after a model by Michelangelo, ca. 1538-41, documented in Seville 1597 (left; IOMR collection); detail of a polychromed bronze crucifix cast by Juan Bautista Franconio, ca. 1597-1600, after a model by Michelangelo and painted by Francisco Pacheco after 17 January 1600 (right; private collection)

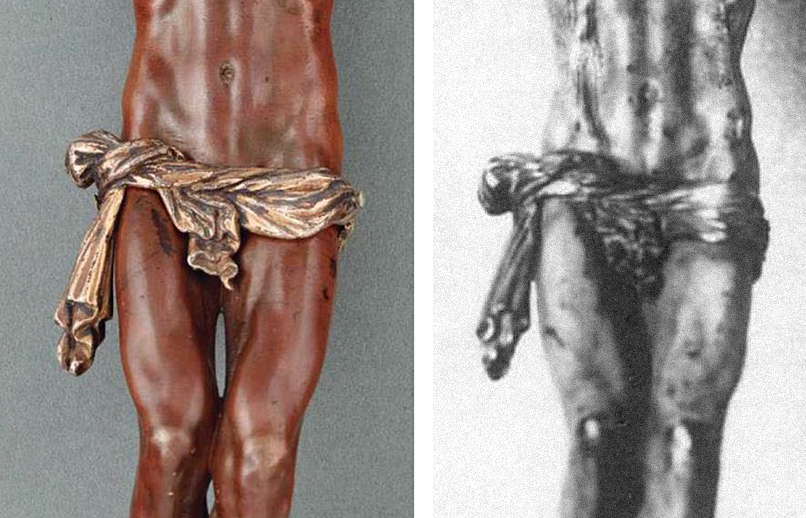

A strong point for the IOMR cast serving as the prototype for subsequent Spanish casts is its perizonium which differs slightly in design from that accompanying the other Roman cast but features identically with the perizonium accompanying one of the first casts made in Spain: that of the polychrome Gandia cast (fig. 6). Franconio appears to later modify the design of this perizonium on his subsequent silver casts, rounding out the otherwise taut feature of the flaring drapery and slightly slumping the perizonium’s knot (fig. 7).15 This later edited version of the perizonium is found on most early casts known throughout Spain. Only two other known Spanish aftercasts reproduce the original IOMR perizonium brought to Spain. One example is a 17th century cast originally in a private collection from Ourense which the present author has previously noted was probably cast after a polychrome bronze example of the crucifix.16 Judging by the depth and feature of the side-wound present on the Ourense cast, it most likely used the Gandia cast as its master model, and thus entailed reproducing also the perizonium which accompanied it: being reflective of the perizonium-type belonging to the IOMR cast.

Fig. 6: Detail of a bronze crucifix, after a model by Michelangelo, ca. 1538-41, documented in Seville 1597 (left; IOMR collection); detail of a polychromed bronze crucifix cast by Juan Bautista Franconio, ca. 1597-1600, after a model by Michelangelo and painted by Francisco Pacheco after 17 January 1600 (right; Grand Ducal Palace of Gandia)

Fig. 7: Detail of a bronze crucifix, after a model by Michelangelo, ca. 1538-41, documented in Seville 1597 (left; IOMR collection); detail of a silver crucifix after a model by Michelangelo, cast by Juan Bautista Franconio, ca. 1600 (right; Gomez-Moreno Museum; photo © Fundacion Rodriguez-Acosta)

A second example involves one of five newly discovered casts of the crucifix the present author herewith presents in this paper (no. 29, figs. 10, 26). An art market example from the 17th century features the same perizonium type observed on the IOMR cast and offers some possible data concerning what may have happened to the IOMR cast after it theoretically left the estate of Peñalosa in 1633. It seems the crucifix may have become the temporary property of an enterprising, although probably provincial, Spanish silversmith during the mid-to-latter part of the 17th century and quite possibly a silversmith once active in the workshop or circle of Andres de Campo Guevara who produced at least one cast of the crucifix during or before 1631 in Astorga where Peñalosa was canon.17

Fig. 8: Detail of a gilt silver crucifix after a model by Michelangelo, probably cast by Andres de Campo Guevara, ca. 1630-31 (left; Museo de los Caminos Astorga); detail of a gilt copper crucifix after a model by Michelangelo, circle or atelier of Andres de Campo Guevara, ca. mid-17th century (right; art market)

The silversmith responsible for this newly published art market example is clearly a provincial artist not particularly adept. They may have used Andres’ moulds for casting this example, or were inspired by his treatment of the cast, adjudged by changes Andres made to the hair of Christ on his example (fig. 8). This newly published cast (no. 29) makes further liberal adjustments to the original model, heavily engraving the form of Christ’s hair in an even more simplified linear manner while adjusting the character of Christ’s face, heightening the veins along the arms and legs, and attempting to emulate some features of the IOMR cast, albeit in a naïve manner through the articulation of chased cold-worked details like the creases along Christ’s forehead, the areole of the nipples and the dripping side-wound of the torso (figs. 8, 9). This suggests that while the silversmith may have employed Andres’ moulds they still had an awareness of—or access to—the IOMR prototype for reference. Another previously unpublished silver cast of the crucifix appears to use the aforenoted art market example as its model (no. 30, fig. 27), being testament to how the lineage of one group of casts could occur over time in Spain.

Fig. 9: Detail of a bronze crucifix, after a model by Michelangelo, ca. 1538-41, documented in Seville 1597 (left; IOMR collection); detail of a gilt copper crucifix after a model by Michelangelo, circle or atelier of Andres de Campo Guevara, ca. mid-17th century (right; art market)

An owner or workshop once in possession of this art market cast (no. 29), has mounted it to an ebony wood crucifix with generic silver finials typical of the period. This same workshop may have been responsible for affixing the IOMR cast to the similarly produced ebony wood cross with silver finials, to which it was attached sometime after 1633, and possibly during the 18th century or later (fig. 10).18 However, the presence of the IOMR cast—theoretically being retained by a series of silversmiths in Spain—may also attest as to why it never entered any ecclesiastic collections.19 If we presume the prototype was once in Astorga, its subsequent presence in Northern Spain, implies it did not travel far during the next few centuries after theoretically arriving there with Peñalosa.

Fig. 10: A bronze crucifix, after a model by Michelangelo, ca. 1538-41, documented in Seville 1597 (left; IOMR collection); a gilt copper crucifix after a model by Michelangelo, circle or atelier of Andres de Campo Guevara, ca. mid-17th century (right; art market)

Distinctions and similarities concerning the two identified Roman casts of Michelangelo’s crucifix

While both the example in a private American collection and the IOMR crucifix clearly originate in the same Roman environment—determined by their coeval quality, assembly, and facture: being hollow cast even into the extremities of the hands and feet and assembled in alike manner; the dating of their casting may differ, adjudged by distinctions between them that are both obvious and subtle.

The cold-work present on the IOMR cast is the most distinguishing characteristic, introducing a bleeding wound to Christ’s torso, embellishing the brow line with a series of punches made with a curved chisel and carefully tracing a crease along Christ’s lower forehead while adding an additional chased crease above it. As noted in Starkie’s analysis of the IOMR cast, the bleeding wound was not part of Michelangelo’s original model20 and this is quite likely true of the exaggerated wrinkles on the forehead, particularly evident if compared against Michelangelo’s treatment of Christ’s face on his marble Pietà at Saint Peter’s Basilica. The textured brows are likewise incompatible with Michelangelo’s original invention. However, these features inform us of the influences of whoever was responsible for the cold-working of this cast, and as noted by Starkie, helps to suggest a period for its casting, as regards the bleeding wound which would tempt a date in or before 1566 when Pope Pius V sought canonized representations of Christ absent of suffering.21

While both Roman casts appear to have a burnished texture applied to their surface areas, the American cast features more burnishing than that of the IOMR cast and is also more deeply burnished, perhaps intended to ‘catch’ a darker patinated finish for its final presentation.

Although superficial and subtle, the piercings on the palms and feet of the American cast have a smaller diameter than that of the IOMR example. It is worth noting that the earliest casts in Spain, attributed to Franconio, also feature these larger piercings, and further encourages the IOMR example as the master model used in Spain.

Another difference between the Roman pair are the casting holes used for sprues or vents on Christ’s head. Both feature a commensurate open hole located along the back of Christ’s head, presumably to assist in mounting a crown-of-thorns. There are two further holes along the sides of Christ’s head on the IOMR cast. One is visibly plugged while the other remains open and was probably used to further support the once present crown-of-thorns. These holes would have been patched and corrected on the wax model prepared for Franconio’s initial casts of the crucifix in Spain and these corrections are visibly—although subtly—observed reproduced on the polychrome bronze cast in a private collection and on the silver cast at the Rodríguez Acosta Foundation, altogether indicative of the IOMR cast being the master model used by Franconio in Spain (fig. 11). There are no visible holes along the sides of Christ’s head on the Roman cast in an American collection. However, if they were present, they may have been plugged and successfully concealed by its patination.

Fig. 11: Detail of a bronze crucifix, after a model by Michelangelo, ca. 1538-41, documented in Seville 1597 (top and bottom left; IOMR collection); detail of a polychromed bronze crucifix cast by Juan Bautista Franconio, ca. 1597-1600, after a model by Michelangelo and painted by Francisco Pacheco after 17 January 1600 (top right; private collection); detail of a silver crucifix after a model by Michelangelo, cast by Juan Bautista Franconio, ca. 1600 (bottom right; Gomez-Moreno Museum; photo © Fundacion Rodriguez-Acosta)

Both casts feature one further ‘primary’ hole at the crown of Christ’s head. Uniquely, this hole on the IOMR cast is smaller than that of the American cast and is plugged differently. In the present author’s opinion, this further encourages an earlier dating for the IOMR cast. A very fine cast example of Gugleilmo’s crucifix model of 1571, formerly belonging to the Roman Capponi family,22 is rather similar in facture, with holes present on the sides of Christ’s head for supporting a crown-of-thorns and only a small hole, expertly plugged and covered by its gilding, at the crown of Christ’s head. In the present author’s opinion, this advocates Guglielmo’s possible oversight of its casting. The American cast features a larger hole at this location and features a filed plug that slightly rises above the surface of the model. This is presumably a later method of facture employed in Guglielmo’s workshop and probably one introduced by Bastiano Torrigiani after becoming a regular founder in Guglielmo’s studio during the late 1560s or early 1570s and certainly before 1573.23 This same style of plug is featured on other early bronze corpora produced by Torrigiani, and certainly on later ones like that accompanying the altar service he produced for Pope Gregory XIII in 1581,24 and is the same method used by Franconio when casting his first examples in Spain (fig. 12), presumably having learned the process from Torrigiani.

Fig. 12: From left-to-right: detail of a bronze crucifix, after a model by Michelangelo, ca. 1538-41 (center; private collection; photo: © GCF); detail of a polychromed bronze crucifix cast by Juan Bautista Franconio, ca. 1597-1600, after a model by Michelangelo and painted by Francisco Pacheco after 17 January 1600 (private collection); detail of a silvered bronze crucifix attributed to Bastiano Torrigiani or workshop, ca. 1580s, after a model by Guglielmo della Porta (Grimaldi Fava collection, photo: Paolo Terzi); detail of a crucifix from a relief of Mount Calvary, attributed to Bastiano Torrigiani, after an original model by Guglielmo della Porta; Rome, Italy; ca. 1577-86 (Budapest Museum of Fine Arts, inv. 51, photo: courtesy of Miriam Szőcs)

One further distinction between the Roman casts is that the hair of the American cast is slightly higher in relief along the top of the head and particularly where the hairline meets Christ’s neck and shoulders or the flesh of the forehead. There appears to be some loss of fidelity in this region on the IOMR cast, although this may not have been present when Franconio brought the crucifix to Spain and produced his initial casts, as these features are somewhat more distinct on the first polychrome bronze casts, for example. Rather, this minor loss of fidelity may be due to the regular handling or exposure the crucifix experienced while being handled and worn by Cespedes. In addition, it may be taken into consideration how the IOMR cast was probably also subsequently handled and further used by later silversmiths, like Andres de Campo Guevara, for further cast examples.

A significant distinction between the Roman casts is their accompanying perizonia with the American cast being accompanied by a gilt bronze perizonium and the IOMR cast being accompanied by a gilt silver perizonium. This distinction between the pair is almost certainly due to the differing periods in which they were cast. The perizonium accompanying the American cast was very likely produced commensurate with the corpus itself. Its crisp detail and quality indicate they were made from a freshly developed model in Guglielmo’s workshop (fig. 13, left). The perizonium dips lengthier and more sharply along the proper left hip of Christ whereas the perizonium accompanying the IOMR cast is slightly shorter and more rounded-out in this feature (fig. 13, right). The XRF data concerning the IOMR perzonium also indicates its facture belongs to the last quarter of the 16th century25 and was quite possibly added by Franconio himself sometime before leaving Rome for Seville. The rubbing and losses to the gilding and presence of gesso residue on the IOMR perizonium suggests it too was used to produce further casts of it. Such observations are commensurate with the already discussed use of the IOMR perizonium as a prototype for one or more casts made in Spain just prior to its reinvention by Franconio observed accompanying his silver casts of the crucifix.26

Fig. 13: A gilt bronze perizonium, workshop of Guglielmo della Porta or Bastiano Torrigiani (left; private collection; photo: © GCF); a gilt silver perizonium, possibly cast during the 1590s by Juan Bautista Franconio, after a model from the workshop of Guglielmo della Porta (right; IOMR collection)

Additional support for the crucifix’s association with Vittoria Colonna

The present author has suggested Guglielmo della Porta may have received Michelangelo’s wax model of the crucifix around 1538-41, not long after Guglielmo had arrived in Rome, befriended Michelangelo and had offered to cast a wax model of a horse statuette Michelangelo had made for Francesco Maria della Rovere, Duke of Urbino, in 1537, after a previous attempt by another unidentified bronze founder had failed.27 The present author hypothesized that Michelangelo may have deferred his next small bronze casting project to Guglielmo: presumably a crucifix for a convent Michelangelo’s beloved friend, Vittoria Colonna, had hoped to build on family property along Monte Cavallo.28 However, the project would be abandoned when plans for the convent never materialized and Vittoria Colonna died in 1547. The present author has proposed certain letters exchanged between Michelangelo and Colonna refer to this sculpture while their exchange of poetry relates to the sculpture’s unique portrayal of Christ crucified.29 The sculpture further emphasizes the beliefs of the Spirituali, a small circle of pre-Reformation Catholic reformers who believed salvation came through faith alone and not through works or through the church. The exchange of personal art and poetry, reflective of their beliefs, was a prized practice among the group.30

This is reflected in a scarcely known autograph finished drawing by a Northern artist who found himself immediately in the context of this movement in Rome and in Michelangelo and Colonna’s immediate orbit between 1537-38. In 1537, the artist, Lambert Lombard, had been tasked by his patron, Érard de la Marck, prince-bishop of Liège, to travel to Rome in search of antiquities for his palace. Lombard made this journey in the retinue of Cardinal Reginald Pole, an important member of the Spirituali.31

Pole was instrumental in Colonna’s faith, whom she regarded as a ‘prophet,’32 and who Michelangelo held in very high esteem.33 Pole was Lombard’s patron in Rome, for whom he completed a finished painting of the Tabula Cebetis, an allegorical subject pertaining to the tensions between sin and piety. Lombard’s biographer, Dominicus Lampsonius, noted how Lombard discussed art in Rome with members of Pole’s circle, like Bartolomeo Stella and Alvise Priuli, both of whom were friends of Michelangelo and Colonna, respectively.34

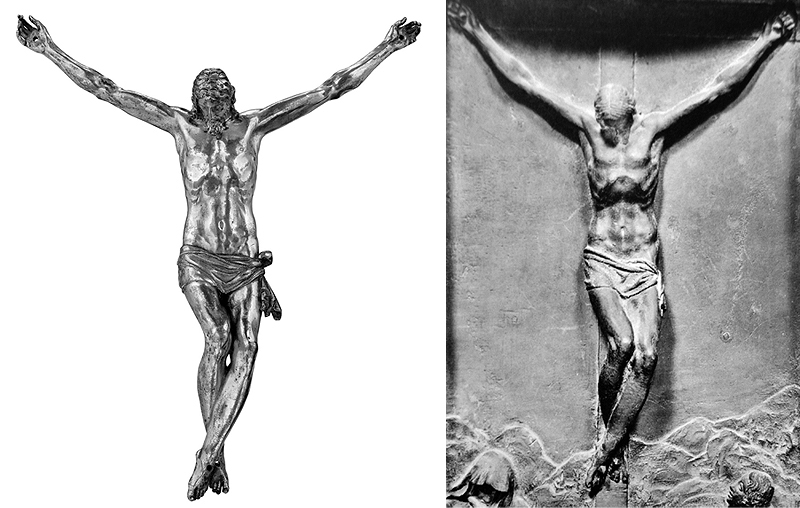

Fig. 14: A finished drawing of Christ on the Cross in pen and brown ink by Lambert Lombard, 1538 (left; Staatliche Museen, Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett, KdZ no. 13175); a bronze crucifix, after a model by Michelangelo, ca. 1538-41 (right; private collection; photo: © GCF)

Lombard’s autograph drawing—a Christ on the Cross—is datable to 1538 (fig. 14, left) on account of its comparison with Lombard’s dated drawings after the Savelli Sarcophagus as well as those he produced after works by Baccio Bandinelli and the Pollaiuolo brothers whose works he had observed in Rome that year.35 Edward Wouk has recently and convincingly suggested the finished drawing of Christ on the Cross was probably made as a gift for his patron, Cardinal Pole.36 Wouk observes how the drawing ‘fuses elements from two of Michelangelo’s drawings for Colonna [a Pietà and Crucifixion-ed.] into a complex, multivalent image with interlocking historical and spiritual purposes,’37 exemplifying Lombard’s talent to independently understand and reconfigure Michelangelo’s inventions in the context of his own gift-giving among the Spirituali. However, unbeknownst to Wouk, and unlike the two aforenoted drawings, is the unique frontally nude portrayal of Christ which is not unique to Lombard’s inventive powers, but again, is a further amalgam of Michelangelo’s creations for Colonna, in this case, inspired by the preparatory drawings Michelangelo may have produced for the crucifix or from Lombard’s immediate witness of the sculptural model itself.38

Lombard’s drawing further locates Michelangelo’s invention of the crucifix in the context of his exchanges and friendship with Colonna. If Lombard refers to Michelangelo’s model as a source for his finished drawing of Christ on the Cross, it could suggest Michelangelo’s crucifix was completed as early as 1538, as Lombard left Rome in that year to return to Liège.

Details concerning Guglielmo and his School

After Guglielmo della Porta’s theoretic receipt of the model of Michelangelo’s crucifix, it would presumably remain in his studio until tensions arose between him and Michelangelo over the monumental tomb of Pope Paul III, thus ending their friendship not long after its receipt.39 Additionally, Michelangelo may not have been apt to request the model back after his deep mourning following Colonna’s death.40 If accurate, it is to be presumed Guglielmo may have first begun considering how to approach casting a crucifix during the 1540s and may have experimented with the process during this time. Guglielmo’s comment to Bartolomeo Ammannati in a letter of 1569 mentions: ‘I have turned my endeavours once again to several figures of Christ on the cross,’ 41 intended for casting, which lends the notion Guglielmo had earlier experimented with making crucifixes before his prolific production of them from 1569 until his death in 1577.42

The present author agrees with Starkie’s proposal that Guglielmo retained Michelangelo’s wax model privately in his studio and quietly referenced it as inspiration for his own corpora models which would later gain widespread success throughout Italy for more than a century.43 Beginning in 1569, Guglielmo commences in marketing his crucifix models while aiming to gain the patronage and graces of Pope Pius V, Emperor Maximillian, and Cardinal Alessandro Farnese.44 Starkie’s proposal that Guglielmo and his school’s dependency on the success of their models, inspired by this sculpture, necessitated that the original work be kept private and this appears to be the case given that only two identified casts after the original model are currently known to survive while its use in Rome features only once in 1574 when Michelangelo’s late assistant, Jacopo del Duca, incorporated a modified and crudely cast example of it on a bronze relief panel of the Crucifixion featured on a tabernacle now preserved at the Charterhouse of San Lorenzo in Padula (fig. 19, right).45

That Michelangelo’s crucifix remained in Guglielmo’s studio, and was probably produced by his assistants, is noted in the present author’s previous analysis and this idea is newly reinforced by Montero’s (CSIC) metallurgical analysis of the alloy of the IOMR cast which—in accordance with Arie Pappot’s (Rijksmuseum) comparative data—indicates its relationship with Guglielmo’s workshop and attests to a Roman origin of the IOMR cast in Guglielmo’s studio during the 1560s.46 This is adjudged by the choice bronze used for its casting, being convenient for cold-work, and using a slightly purified high-copper bronze known as ‘rame peloso,’ employed until the mid-to-late 1550s in Italy and certainly before 1570. Coppel notes that the technical virtuosity used in both the construction, assembly, and casting of the IOMR crucifix must date it from the 1560s onward. Encouraging a period of facture during this decade is further supported by the edits introduced to Michelangelo’s original model prior to its appearance on the Padula tabernacle in 1574. This suggests a minority of casts or plaster moulds of Michelangelo’s original model may have already circulated among the small circle of goldsmiths and bronze-workers in Rome before the end of 1573.47

Fig. 15: Gilt bronze plaquette of the Banquet of the Gods by Jacob Cornelis Cobaert after a design by Guglielmo della Porta, ca. 1560s (Altomani & Sons)

The alloy used for the IOMR cast proved consistent with a suite of three casts reproducing a bronze plaquette relief depicting the Banquet of the Gods inspired by Ovid’s Metamorphoses. This work was originally modeled in clay by Guglielmo’s assistant, Jacobus Cornelis Cobaert, following Gugleilmo’s design during the mid-1550s.48 This suite of plaquettes included XRF tested examples from the Metropolitan Museum of Art (MET),49 the Kunsthistorisches,50 and an example belonging to Altomani & Sons. While the MET example was probably cast in Guglielmo’s workshop, adjudged by its quality, the Kunsthistorisches example is an early aftercast but was probably still made in Rome during the last quarter of the 16th century. The XRF results of the IOMR cast aligned succinctly with the most important example of this group: a gilt bronze cast of the plaquette belonging to Altomani & Sons (fig. 15), which the present author—prior to Starkie’s publication—had already studied and assessed to be a contemporary work made in Guglielmo’s workshop and probably cast and finished by his assistant Jacob Cornelis Cobaert during the 1560s.51 Its detailed surface treatment is characteristic of Cobaert’s manner52 while the chiseling and surface treatment of the relief exemplifies the cold-worker’s familiarity with the original model.53

While the XRF results point to this suite of plaquettes as derivative of Guglielmo and his workshop, it should be noted that plaquettes cast from these models from Gugleilmo’s Metamorphoses series vary considerably in terms of quality, manner of facture, period of facture and finish. Documents point to their reproduction by a variety of bronze founders and goldsmiths during the last quarter of the 16th century. For example, other identifiable casts from this series were produced by members of Guglielmo’s family or circle such as a cast by his eldest son, Fidia della Porta,54 repoussé gold versions made by Caesar Targone, probably during the mid-1580s,55 and possible examples produced by Antonio Gentili da Faenza sometime between 1577-96.56 During the 1590s, a certain goldsmith, Gregorio Gioseppelli, may also have made casts from the series, in particular that of the Banquet of the Gods.57 In spite of these considerations, the IOMR cast aligns with the XRF tested plaquette most evident to be from Guglielmo’s studio, and probably by the hand of Cobaert under Guglielmo’s supervision, thus the crucifix must also align with this period as adjudged by Coppel and Starkie.58

However, while the IOMR cast can reasonably, if not confidently, be dated to the 1560s, it is unlikely to have been cold-worked by Cobaert, as the delineation of the eyebrows and the side-wound of Christ are unlike Cobaert’s treatments and point to someone else active in Guglielmo’s environment. While Guglielmo may have had a variety of collaborators, only a handful are securely identified and we know nothing, for example, of Pier Antonio di Benvenuto Tati’s work, who in 1570 had been tasked, alongside Antonio Gentili da Faenza, to produce a series of gilt silver reliquaries based upon Guglielmo’s designs.59

Fig. 16: Detail of a bronze crucifix, after a model by Michelangelo, ca. 1538-41, documented in Seville 1597 (left; IOMR collection); detail of a repousse gold Pieta or Virgin Mourning the Dead Christ on slate by Cesare Targone, ca. 1586-87 (right; Getty Museum, Inv. 84.SE.121)

The closest parallel to the cold-worked brow line of Christ on the IOMR cast is a superficial comparison against Caesar Targone’s autograph Pietà relief executed in repoussé gold, in which the brow line of Christ is similarly peened in an inconsistently spaced, yet similarly angled series of delineated strokes using a slightly curved punch tool (fig. 16). However, no documentary evidence supports Targone’s activity in Rome until he is identified as settling there in 1573-74,60 although it is possible he could have been in Rome before 1568, a period in his career of which little data survives.

The removable perizonia accompanying both Roman casts of the crucifix suggest that these accessory parts were at least made sometime after 1566 when Pope Pius V instituted new standards of decorum for nude sculptural works.61 The present author has previously noted that the style of these perizonia is indicative of those connected to Guglielmo, evident in his wax Christ belonging to a Crucifixion group, ca. 1557-68, at the Galleria Borghese (fig. 17) and those reflected on integral perizonia on crucifixes cast by his protégé, Bastiano Torrigiani, from the 1580s which follow Guglielmo’s models.62 While the invention of the removable perizonia which accompany these casts may date sometime after 1566, it remains possible still that the casting of the crucifixes may predate their invention. This might especially be true of the IOMR example, whose perizonium is more obviously a later addition and one modeled after an example that must have been available to Franconio, presumably from within Torrigiani’s workshop.63

Fig. 17: Detail of a wax relief of the Crucifixion on slate, attributed to Guglielmo della Porta, ca. 1557-68 (left and right; Galleria Borghese, Rome); a gilt bronze perizonium, workshop of Guglielmo della Porta or Bastiano Torrigiani (center; private collection; photo: © GCF)

The other Roman cast in an American collection could date to a later period, perhaps the early 1570s or possibly even the 1580s, a duration of time in which crucifixes were being regularly produced in Guglielmo and Torrigiani’s workshops. An eventual metallurgical analysis of the American cast could help resolve this question.

Torrigiani’s expertise in producing crucifixes is attested by his former pupil, Baldo Vazanno da Cortona, who noted he ‘had crucifixes and models to make crucifixes, moulds and wax models of different figures’ in his workshop.64 Documented crucifixes produced by Torrigiani include the aforenoted example commissioned in 1581 as part of an altar service for San Giacomo Maggiore in Bologna,65 as well further examples made in 1583, later donated to St. Peter’s Basilica,66 and another, also in 1583, cast in silver for Simonetto Anastagi.67

Cobaert’s involvement in this type of production is less known. He was certainly a master of relief sculpture working from designs by Guglielmo but he was also capable of casting and finishing figures in-the-round, adjudged by the bronze statuettes attributed to him which adorn a tabernacle at the Chiesa di S. Luigi dei Francesi in Rome.68 A testimony of Bartolomeo da Turino in 1609, describes Cobaert’s possession, ca. 1590, of ‘crucifixes and reliefs’ he made,69 suggesting Cobaert’s hand in the modeling of some corpora based on Guglielmo’s sketches. This idea is further affirmed in Raffaello Vaiani’s casting of Cobaert’s ‘low relief Passion and a crucifix in-the-round,’ ‘by his [Cobaert’s-ed.] hand,’ for their shared patron, Simonetto Anastagi, in 1589.70

Addendum to the census of known casts after Michelangelo’s crucifix

In the previous census of examples of Michelangelo’s crucifix, the present author discussed their differences, possible origins, and the paternity of various casts.71 Starkie’s research has brought some additional data to this discussion. Starkie agrees with the present author concerning five casts believed produced by Franconio in Spain: two in bronze—both polychromed by Pacheco—being casts in a private collection and one at the Ducal Palace of Gandía, as well as three silver casts located at the Cathedral of Seville, the Royal Palace of Madrid and one belonging to the Rodríguez Acosta Foundation in Granada and formerly with the art historian, Manuel Gómez Moreno, who initially recognized it as a work by Michelangelo.72

Fig. 18: Polychrome pewter crucifix, probably 17th century, after a model by Michelangelo, ca. 1538-41 (Cuenca Cathedral)

Of interest is the polychrome cast at Cuenca Cathedral published by Starkie (fig. 18).73 While the cast is quite faithful in its detail, its polychromy exhibits differences from the other polychrome examples and its metallic content indicates it is cast in pewter and thus must be relegated to a 17th or 18th century dating.74 This removes this cast from the present author’s previous speculation that it could have been an example produced by Franconio and Pacheco.

Starkie suggests the example at the MET may not be of Italian origin, but rather, could derive from Spain,75 recently adjudged also by James David Draper,76 due to its quality and characteristics. However, the present author retains the idea it could belong somewhere in the vicinity of Jacopo del Duca’s activity, chiefly on account of its lackluster quality, edited feature of raised arms and Italian provenance. These edited characteristics correspond with Jacopo’s feature of Michelangelo’s model on the tabernacle relief of 1574 (‘Padula cast’).77 On that relief, Jacopo further edits the model by introducing a perizonium, turning the head of Christ, closing Christ’s proper left hand, tucking, and slightly turning his knees and further elevating Christ’s arms to properly accommodate the model on the prefixed scale of the relief panel (fig. 19, right).78 Michelangelo’s invention of the crucifix and its subsequent theoretic transfer to Guglielmo’s workshop predates Jacopo’s period of collaboration with Michelangelo and it could be surmised that Jacopo’s access to the model came through other means during or prior to 1573, and presumably by means of someone connected with Guglielmo’s workshop, possibly Torrigiani.79

Fig. 19: A gilt bronze crucifix presumably treated (by Bresciano?) after a model from Jacopo del Duca’s studio, after a model by Michelangelo, after 1574 (left; art market); detail of a bronze Crucifixion panel, shown in reverse, for a tabernacle by Jacopo del Duca, 1573-74 (left; Certosa di San Lorenzo, Padula)

In the previous census, the present author cited another cast which relates to the Padula cast but remodels the face of Christ anew and replaces the forked beard of Christ with a full one while exchanging the Roman arched series of muscles along the costal margin of Christ’s torso with a pointed arched manner (fig. 19, left). It could be presumed someone in Jacopo’s circle edited the Padula model sometime after 1573 to create this unique version of the model.80

Fig. 20: A gilt bronze crucifix with a removable silver perizonium attributed to Prospero Antichi, ca. 1587-99, Rome (Metropolitan Museum of Art, inv. 44.142.2)

The same sculptor responsible for the edits to the aforenoted cast may also be responsible for a freely modeled nude crucifix-type known by a handful of fine examples preserved at the MET (fig. 20),81 Museo Diocesano di Mantova,82 Museo Civico di Udine,83 Museo Diocesano y Catedralicio in Lugo (Galicia, Spain), Collegio Alberoni in Piacenza84 and one formerly in the collection of Albert Eperjesy de Szászváros et Toti.85 The artist responsible for this work had access to Michelangelo’s original model or a quality cast of it for use as reference in developing his free invention based upon it (fig. 21).

Fig. 21: Detail of a bronze crucifix, after a model by Michelangelo, ca. 1538-41, documented in Seville 1597 (above; IOMR collection); detail of a gilt bronze crucifix attributed to Prospero Antichi, ca. 1587-99, Rome (bottom; former collection of Albert Eperjesy de Szászváros et Toti)

Distinct to this sculpture is the repositioning of Christ’s legs in the traditional form, with Christ’s proper right foot crossing over his left foot in the three-nail format. The arms and legs are thinned-out but the sculptor reproduces again the same pointed arched series of muscles along the costal margin of the torso and likewise similarly reinvents the demeanor of Christ’s face. A sketch preserved at the Louvre is frequently associated with Michelangelo’s crucifix, but more accurately reflects this adapted version by another sculptor (fig. 22).

Fig. 22: Studies for a crucified Christ, school of Michelangelo, 16th cent., Rome (Louvre, inv. 10903, Recto)

The present author has previously discussed a terminus ante quem for this crucifix, established by the example preserved on an altar cross at the Museo Diocesano di Mantova which features a cast silver applique of the arms of Pope Clement VIII along its stepped base, presumably indicating Clement VIII was the patron of the altar cross.86 The altar cross must date from before 1598 when it was in the possession of the pope who subsequently donated it to Duke Vincenzo I Gonzaga in that year.87 The Duke afterward donated it to the Gonzaga family chapel at the Church of Santa Barbara on 20 April 1599 where it remained until eventually being transferred to the museum.88

The inventor of this nude crucifix adds a removable silver perizonium, and although applied using a pin and hinge hidden along its reverse, it takes its essential concept from a probable observation of the removable perizonia developed in Guglielmo or Torrigiani’s workshop. These corpora are also expertly hollow-cast in the same manner as the two Roman casts of Michelangelo’s crucifixes: being hollowed through the hands and feet. It is to be speculated if its inventor may thus have had exposure to Torrigiani’s immediate environment, witting of the facture of crucifixes and removable perizonia, and having possible access to Michelangelo’s original model for reference. Because of these observations the present author earlier suggested this crucifix could be Torrigiani’s invention.89 However, a more likely artist may emerge on account of recent observations made by Lorenzo Principi who brings to light its association with a life-size bronze variant of the model preserved in the Sacchetti Chapel at the Chiesa da San Giovanni dei Fiorentini in Rome (fig. 23). Although not cast until 1620-24 by Paolo Sanquirico, the crucifix was originally commissioned by Cardinal Giacomo Savelli in 1587 to be made by the sculptor, Prospero Antichi (called il Bresciano) and intended for the interior of the Chiesa del Gesù.90 The casting of this crucifix was to be managed by Jacopo’s brother and occasional collaborator, Lodovico del Duca.91 However, the project was never completed, although plans emerged for its casting by Sanquirico in the 17th century, destined for the Sachetti Chapel at Fiorentini.

Fig. 23: Bronze crucifix modeled by Prospero Antichi and Lodovico del Duca following Antichi’s design, ca. 1587-1603, cast by Paolo Sanquirico, ca. 1620-24 (Sacchetti Chapel, San Giovanni dei Fiorentini, Rome)

Although Lodovico was originally tasked to cast the life-size crucifix, Bresciano had earlier experience in such projects just prior to his arrival in Rome. This is evinced by his creation of a life-size bronze crucifix for the Oratory of the Holy Trinity in Valdimontone, Siena, completed in 1576, and installed the following year.92 Bresciano’s own talents in bronze are noted in Filippo Baldinucci’s 1702 recollection of Domenico Crésti’s possession of a bronze cast crucifix by Bresciano that Crésti refused to have finished by anyone but that master himself,93 indicating Bresciano’s talents in cold-working bronze, presumably with the eloquence of a goldsmith, adjudged by the previous noted and highly refined private devotional examples of the model which survive. It is worth noting the perizonia of these small corpora correspond also with those cast integral on the two life-size crucifixes produced by Bresciano, further encouraging his authorship of their smaller-scale variants (fig. 24).94

Fig. 24: Detail of the perizonium on a bronze crucifix modeled by Prospero Antichi and Lodovico del Duca following Antichi’s design, ca. 1587-1603, cast by Paolo Sanquirico, ca. 1620-24 (left; Sacchetti Chapel, San Giovanni dei Fiorentini, Rome); detail of a removable silver perizonium on a gilt bronze crucifix attributed to Prospero Antichi, ca. 1587-99, Rome (center; Metropolitan Museum of Art); detail of the perizonium on a bronze crucifix by Prospero Antichi, 1576 (right; Oratory of the Holy Trinity in Valdimontone, Siena)

That Torrigiani may have collaborated or, at minimum, consulted with Bresciano during the 1580s is most recently—and persuasively—elaborated by Emmanuel Lamouche.95 However, an initial intersection of the artists could have occurred in respect to Bresciano’s earliest documented presence in Rome, lodging along via Giulia in Guglielmo della Porta’s former property in 1579, paying rent to his son, Fidia della Porta, while Fidia and Torrigiani were still sorting through the machinations of Guglielmo’s final will.96

Bresciano and Torrigiani may certainly have encountered one another by 1588 when Torrigiani was tasked with casting the statue of St. Peter for the top of Trajan’s Column and Bresciano, along with Pietro Paolo Olivieri, were tasked with evaluating the model prior to its casting.97 However, the intersection of Bresciano and Torrigiani is certainly affirmed on 30 January 1591 when Torrigiani was appointed bronze founder of the Apostolic Chamber and Bresciano was appointed the same, albeit as sculptor of marbles and ‘works to be made in metal,’ under the auspices of Pope Gregory XIV.98 This novel circumstance—unprecedented for its time—was orchestrated by the Pope’s nephew, Cardinal Paolo Emilio Sfondrati, and may have contractually aligned what was presumably an already successful working relationship between the two artists.

It could be due to this period of collaboration that the small devotional examples of Bresciano’s corpora were produced. Testifying to this possibility are the specific terms outlined for the Apostolic Chamber which note Torrigiani could not cast any statues or statuettes financed by the Apostolic Chamber in bronze if the models were not made by Bresciano.99 Although this official collaborative partnership may have dissolved nine months later, after the death of Gregory XIV, it could have continued well into Pope Clement VIII’s tenure, thus resulting in an example like that featured on the altar cross preserved at the Museo Diocesano di Mantova. Torrigiani remained at his post within the Apostolic Chamber into the tenure of Clement VIII until Torrigiani died in 1596.

That the casting quality of Bresciano’s corpora so closely relate to that of the Roman casts of Michelangelo’s model suggests Torrigiani’s involvement in their possible facture and finishing. Even if cast in the 1560s we might wonder if the IOMR cast may have been cold-worked later by Bresciano. The treatment of five drops of blood on Christ’s side-wound articulated on the MET cast of Bresciano’s crucifix superficially relates to that featured on the IOMR cast (fig. 25). That the Roman casts could potentially date to the 1580s or even the early 1590s, should also not be ruled out, and may place them within the closer immediate awareness of Franconio who would been made aware of them during the 1590s, and would travel with his example to Seville in 1597.100

Fig. 25: Detail of a bronze crucifix, after a model by Michelangelo, ca. 1538-41, documented in Seville 1597 (left; IOMR collection); detail of a gilt bronze crucifix attributed to Prospero Antichi, ca. 1587-99, Rome (right; Metropolitan Museum of Art)

New additions to the census published in 2021

Fig. 26: a gilt copper crucifix after a model by Michelangelo, circle or atelier of Andres de Campo Guevara, ca. mid-17th century (art market; Templum Fine Arts)

No. 29 (figs. 8, 9, 10, 26)

Made: probably ca. mid-to-late 17th century; possibly area of Astorga, Spain

Cast: possibly by a descendant or member of the circle of Andres de Campo Guevara

This example is probably cast in bronze with a high copper content and gilded. It is accompanied by a silver cast removable perizonium that appears to directly derive from that accompanying the IOMR cast. The cold worked details of its surface appear to use the IOMR cast as a point of reference, particularly as regards the placement and style of Christ’s side wound as well as the feature of wrinkles along his forehead (figs. 8, 9). The features of Christ’s face are edited to express a higher degree of suffering than what is presented on the original model and shows the intervention of the gold or silversmith responsible for this cast.

The uniquely flattened and striated hair of Christ is echoed in the treatments introduced to the original model by Andres de Campo Guevara who incorporated an example of Michelangelo’s crucifix on a metal altar cross he made in 1631 for the Cathedral of Astorga, now preserved at the Museo de los Caminos Astorga (fig. 8).101 It is speculated whether that crucifix was made in tandem with Andres’ altar cross or if it could have been made earlier. The present author believes it was probably made in tandem, judging by the consistency of its finish and that of the associated altar cross.

It is believed Andres could have used the original crucifix brought to Spain by Juan Bautista Franconio, as a model, as it would have theoretically been in Juan de Peñalosa’s possession while serving as canon of the Astorga Cathedral.

That this cast relates to the Astorga example and likewise reproduces the IOMR cast’s perizonium, suggests that the silversmith responsible for this cast probably had an awareness of both the crucifix cast by Andres, as well as the original model brought to Spain by Franconio and is possibly the production of a mid-17th century silversmith operating out of the atelier of Andres.

The ebony wood crucifix with silver finials—to which this cast is attached—conforms closely in scale and format to that which the IOMR cast was mounted.

Fig. 27: A silver crucifix after a model by Michelangelo, circle or atelier of Andres de Campo Guevara, ca. mid-17th century (art market; Templum Fine Arts)

No. 30 (fig. 27)

Made: probably mid-to-late 17th century; possibly area of Astorga, Spain

Cast: probably by a descendant or member of the circle of the silversmith responsible for no. 29

This purely silver cast appears to derive from no. 29, either using the same moulds or producing an aftercast from an example descending from the workshop responsible for producing no. 29. This could suggest the continued lineage of silversmiths originating from the school of Andres de Campo Guervara.

Fig. 28: A gilt bronze crucifix after a model by Michelangelo with accompanying removable silver perizonium (art market, Setdart)

No. 31 (fig. 28)

Made: probably early-to-mid 17th century; Spain

This gilt bronze cast is accompanied by a silver perizonium and must derive from an early aftercast or original silver cast executed by Franconio. The quality is very reasonable and its perizonium-type, along with its subdued surface details, suggest a silver cast was used as its master model.

Fig. 29: Gilt bronze crucifix after a model by Michelangelo (art market, Drouot)

No. 32 (fig. 29)

Made: probably early 18th century; Europe

The present example in gilt bronze is affixed to an ebony wood altar cross with flanking gilt bronze statuettes of Sts. Mary and John. The entire production suggests a late 17th century dating although its quality and facture perhaps indicate a more probable dating to the first part of the 18th century. The models altogether reflect the typologies observed produced in Italy or the Netherlands. The figure of Christ must derive from a rather weak model as its details are overworked or lost and a new perizonium has been introduced, in keeping with the period, and cast integrally with the bronze figure of Christ.

Fig. 30: Gilt bronze crucifix after a model by Michelangelo (art market, Subastas Segre)

No. 33 (fig. 30)

Made: probably late 18th century or early 19th century; Spain

A late and rather crude example in gilt bronze, probably cast in Spain and indicative of the reverence of this model throughout Spain, emblematic of how cast-after-cast was made in honor of Michelangelo’s celebrated invention.

Endnotes

1 Carlos Herrero Starkie (2025): Michelangelo’s Bronze Corpus, Documented in Seville 1597, Rediscovered. Institute of Old Masters Research.

2 Michael Riddick (2021): Michelangelo’s Crucifix for Vittoria Colonna. Renbronze.com (accessed 2025).

3 Ibid. The ‘American cast’ was acquired by its current owner from a family in Florida who had received it as a gift from Cardinal Alfonso Lopez Trujillo. Before Trujillo’s possession of the crucifix in Rome, it is believed to have earlier been part of an estate in Fiesole, Italy.

4 Carlos Herrero Starkie, email communication (November, 2024).

5 C.H. Starkie (2025): op. cit. (note 1), see annexes: Ignacio Montero CSIC, 3 July 2023 “Informe sobre el estudio de un Cristo Renacentista”, and Sara Cavero “Memoria final de Restauración de un Crucifijo de bronce,” August 2023.

6 Francisco Pacheco (1649): Arte de la Pintura (trans. by Enggass-Brown, 1970) Arte de la Pintura in Italy and Spain 1600–1750: Sources and Documents in the History of Art. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, Prentice-Hall, pp. 405-06, 611. Original text: “Micael Angel, clarísima luz de la pintura y escultura hizo para modelo un crucifijo de una tercia con cuatro clavos, que gozamos hoy. El cual trajo á esta ciudad (Seville) vaciado de bronce Juan Bautista Franconio, valiente platero, el año de 1597. Y despues de haber enriquecido con él á todos los pintores y escultores, dió el original á Pablo de Céspedes, racionero de la Santa iglesia de Córdoba que con mucha estimacion lo traia al cuello.”; and “Quiso Dios por su misericordia desterrar del mundo estos platos vidriados, y que con mejor luz y acuerdo se introdujesen las encarnaciones mates, como pintura más natural, y que se deja retocar varias veces, y hacer en ella los primores que vemos hoy, bien es verdad que algunos de los modernos (entre los antiguos y nosotros) las comenzaron á ejercitar, y las vemos en algunas historias suyas de escultura en retablos viejos; pero el resucitarlas en España, y dar con ellas nueva luz y vida á la buena escultura, oso decir con verdad, que, yo he sido de los que comenzaron, si no el primero desde el año 1600 á esta parte, poco más á lo menos en Sevilla, porque el primer Crucifijo de bronce de cuatro clavos de los de Micael Angel, que vació del que trajo de Roma Juan Bautista Franconio (insigne platero) lo pinté yo de mate en 17 de Enero del dicho año.”

7 M. Riddick (2021): op. cit. (note 2), Appendix B, no. 2, pp. 10-11.

8 Ibid., Appendix B, no. 1, pp. 7-8. See also, Don Manuel Gomez-Moreno (1930): Obras de Miguel Angel en España in Archivo Español de Arte y Arqueologia, p. 194; and Anselmo Lopez Morais (1988): Crucifijo de Miguel Angel. Un ejemplar en coleccion particular de Orense. University of La Rioja. p. 7.

9 F. Pacheco (1649): op. cit. (note 6), pp. 405-06, 611. The painting resides in the Gomez-Moreno Museum. Pacheco also referenced the crucifix for a painted panel of 1637, belonging to a Madrid private collection, whose provenance may connect it with a painting of Christ Crucified by Pacheco formerly in the chapel of San Miguel in the church of the Colegio de San Alberto in Seville where it was documented in 1800 by J.A. Ceán Bermúdez. See also Xavier Bray, et al (2009): The Sacred Made Real: Spanish Painting and Sculpture 1600–1700. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC; and C.H. Starkie (2025): op. cit. (note 1), p. 174.

10 Pedro Manuel Martinez Lara (2012): Sedimento material de una vida humanista. El inventario de bienes de Pablo de Cespedes in Boletin de Arte, Nos. 32-33, University of Seville, pp. 437-55.; Fernando Llamazares Rodríguez “Juan de Peñalosa y Sandoval: Enfermedad, Testamento, Muerte y Almoneda, 1633”; F. Pacheco (1649): op. cit. (note 6); M. Riddick (2021): op. cit. (note 2), Appendix B, no. 9, pp. 20-21; and C.H. Starkie (2025): op. cit. (note 1), pp. 51, 84.

11 The lack of this feature and that of the side-wound of Christ on subsequent Spanish casts is not unusual in consideration that the model had a layer of wax applied to its surface prior to the plaster vestment used to produce a subsequent intermodel in wax.

12 M. Riddick (2021): op. cit. (note 2), Appendix B, no. 4, pp. 12-13. See also Carmen Heredia (2007): La Recepcion del Clasicismo en la Plateria Española del Siglo XVI. International Conference “Imagines,” The reception of Antiquity in performing and visual Arts: Universidad de La Rioja, pp. 458-59; and C.H. Starkie (2025): op. cit. (note 1), see Chapter 2.

13 M. Riddick (2021), Ibid., no. 5, pp. 14-15, C.H. Starkie (2025), Ibid., see also D. M. Gomez-Moreno (1930): Obras de Miguel Angel en España in Archivo Español de Arte y Arqueologia, pp. 189-98 and D. M. Gomez-Moreno (1933): El Crucifijo de Miguel Angel in Archivo Español de Arte y Arqueologia, pp. 81-84.

14 M. Riddick (2021), Ibid., no. 6, pp. 16-17.

15 Ibid., Appendix B.

16 Ibid., no. 12, pp. 25-27. See also Marques de Lozoya (1971): Sobre el crucifijo de plata, vaciado segun el modelo de Miguel Angel, en la Caja de Ahorros de Segovia. Publicaciones de la Caja de Ahorros y Monte de Piedad de Segovia, Spain, pp. 8-9 and A. L. Morais (1988): op. cit. (note 8), pp. 6-7.

17 Fernando Llamazares Rodríguez (1982): El Cristo de Miguel Angel y Andres de Campos Guevara en Leon. Tierras de León: Revista de la Diputación Provincial, vol. 22, no. 48, pp. 19-30.

18 Further encouraging this idea is the unusual height of these ebony crosses, not shown in the photo, but which share the same dimensions of scale. The silver finial that would have once capped the base of the ebony cross of the IOMR cast is lost. XRF analysis of the IOMR cast’s crucifix finials indicated they were ‘modern.’

19 This latter observation is noted by Starkie (email communication, February 2025).

20 M. Riddick (2021): op. cit. (note 2), p. 7 and footnote 18; C.H. Starkie (2025): op. cit. (note 1), pp. 30-31.

21 This characteristic of the IOMR cast and its relevance in dating the cast is discussed by Rosario Coppel and C.H. Starkie, Ibid.

22 For a discussion of this crucifix see M. Riddick (2017a): Reconstituting a Crucifix by Guglielmo della Porta and His Colleagues. Renbronze.com (accessed February 2025). A silver cast of equivalent fine quality is featured on a silver and ebony wood house altar preserved in the Monastery of El Escorial in Spain, inv. 10048054.

23 Emmanuel Lamouche (2022): Les fondeurs de bronze dans la Rome des papes (1585- 1630). École française de Rome, p. 82.

24 This altar suite was destined for San Giacomo Maggiore in Bologna. Andrea and Stefano Tumidei Bacchi (2002): Il Michelangelo incognito: Alessandro Menganti ew la arti a Bologna nell’eta della Controriforma. Edisai SRL, pp. 228-36.

25 C.H. Starkie (2025): op. cit. (note 1), Annex 1.

26 M. Riddick (2021): op. cit. (note 2), Appendix B.

27 Ibid., p. 14. Correspondence concerning this project dates from July to November 1537. See Paul Joannides (1997): Michelangelo Bronzista: Reflections on his Mettle. Apollo, 145/424, June, pp. 11-20, and Mary Hollingsworth (2010): Art Patronage in Renaissance Urbino, Pesaro, and Rimini, c. 1400-1550. The Court Cities of Northern Italy: Milan, Parma, Piacenza, Mantua, Ferrara, Bologna, Urbino, Pesaro, and Rimini. Cambridge University Press, UK, p. 352. For Guglielmo’s petition to cast the horse on behalf of Michelangelo and his patron, see P. Joannides, Ibid., p. 9, docs. 18-20.

28 For the letter of permission Paul III gave Colonna to build the convent, see Maria Forcellino (2016): Vittoria Colonna and Michelangelo: Drawings and Paintings. A Companion to Vittoria Colonna. The Renaissance Society of America, vol. 5, pp. 270–313; and Ascanio Condivi (1553): The Life of Michelangelo in Michelangelo Buonarroti by Charles Holroyd, Keeper of British Art, with translations of the life of the master by his scholar, Ascanio Condivi, and three dialogues from the Portuguese by Francisco d’Ollanda. Duckworth & Co., London (1903), p. 275.

29 M. Riddick (2021): op. cit. (note 2), Appendix A.

30 For details on Colonna’s involvement in the Spirituali and references to the portrayal of Christ among this group see Abigail Brundin (2008): Vittoria Colonna and the Spiritual Poetics of the Italian Reformation. Ashgate Publishing, UK; Emidio Campi (2016): Vittoria Colonna and Bernardino Ochino. A Companion to Vittoria Colonna. The Renaissance Society of America, Vol. 5, pp. 371-98; and Una Roman D’Elia (2006): Drawing Christ’s Blood: Michelangelo, Vittoria Colonna, and the Aesthetics of Reform. Renaissance Quarterly, Vol. 59, Issue 1. Thomson Gale.

31 Godelieve Denhaene (1990): Lambert Lombard: Renaissance et humanisme à Liège. Antwerp, pp. 15-17.

32 For a recent summary on Vittoria Colonna and Cardinal Reginald Pole’s relationship see Ramie Targoff (2021): Late Love: Vittoria Colonna and Reginald Pole in Vittoria Colonna. Amsterdam University Press, pp. 55-72.

33 A succinct summary of Michelangelo’s intersection with Pole is most recently outlined by Sarah Vowles (2024): Between faith and heresy: Michelangelo in the 1540s. British Museum exhibition blog. BritishMuseum.org (accessed March 2025).

34 Maria Cali (1980): Da Michelangelo all’Escorial: momenti del dibattito religioso nell’arte del Cinquecento. Turin. See also Dominicus Lampsonius (1565): Lamberti Lombardi apud Eburones pictoris celeberrimi Vita – The Life of Lambert Lombard (1565); and Effigies of Several Famous Painters from the Low Countries, (trans. by Edward H. Wouk with Helen Dalton and Julene Abad del Vecchio, 2021). Los Angeles.

35 Ibid. See also G. Denhaene (1990): op. cit. (note 31), pp. 65–76; and Ellen Hühn (1970): Lambert Lombard als Zeichner, Ph.D. diss., University of Münster, pp. 35–41.

36 Edward Wouk (2023): Michelangelo, Lambert Lombard, and the Inalienable Gift of Drawing in Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte, vol. 86, no. 1, pp. 15-49. G. Denhaene first suggested this possibility in G. Denhaene (1990): op. cit. (note 31), p. 104.

37 E. Wouk (2023), Ibid.

38 That Lambert Lombard may have observed sketches in preparation for Michelangelo’s sculpted crucifix is inferred by drawings often associated with this project, amply reproduced in M. Riddick (2021): op. cit. (note 2) and C.H. Starkie (2025): op. cit. (note 1), although some sketches at the Uffizi, attributed to Alessandro Allori’s period in Rome, from 1554-60, may preserve copies of lost drawings for this project. See for example, Uffizi invs. 10238 and 10256.

39 Rosario Coppel (2012): Guglielmo della Porta in Rome in Guglielmo della Porta: A Counter-Reformation Sculptor. Coll & Cortes, p. 34.

40 The impact of Colonna’s death on Michelangelo is articulated in Abigail Brundin (2005): Sonnets for Michelangelo. University of Chicago Press. See also A. Brundin (2008): op. cit. (note 30).

41 R. Coppel (2012): op. cit. (note 39).

42 Guglielmo’s serial production of crucifixes is most recently outlined in R. Coppel (2012): op. cit. (note 39).

43 C.H. Starkie (2025): op. cit. (note 1), pp. 124-26.

44 R. Coppel (2012): op. cit. (note 39).

45 M. Riddick (2021): op. cit. (note 2), pp. 8-11. Details concerning this project are further elaborated in Gonzalo Redin (2002): Jacopo del Duca, il ciborio della certosa di Padula el il ciborio di Michelangelo per Santa Maria degli Angeli. Antologia di Belle Arti, 63-66, pp. 125-138; Jennifer Montagu (1996): Gold, Silver & Bronze: Metal Sculpture of the Roman Baroque. Princeton University, p. 24 and Appendix A; and Philippe Malgouyres (2011): La Deposition du Christ de Jacopo Del Duca, chef-d’oeuvre posthume de Michel-Ange. La Revue des Musees de France: Revue du Louvre 2011-5, RMN-Grand Palais, Paris, pp. 43-56.

46 C.H. Starkie (2025): op. cit. (note 1), p. 68.

47 Jacopo del Duca’s cast of the Crucifixion relief panel for the Padula tabernacle was executed on 27 January 1574, suggesting Jacopo was experimenting with the model toward the end of 1573, at the latest. G. Redin (2002): op. cit. (note 45).

48 Antonino Bertolotti (1881): Artisti lombardi a Roma, II. Milan, pp. 140-43 and Giovanni Baglione (1642): Le vite de’ pittori scultori et architetti. Dal pontificato di Gregorio XIII del 1572. In fino a’ tempi di Papa Vrbano Ottauo nel 1642. Rome, p. 100. A sketch of this composition by Guglielmo della Porta is preserved at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY, inv. 63.103.3.

49 Metropolitan Museum of Art, inv. 38.152.2.

50 Kunsthistorisches, Kunstkammer, 7761.

51 C.H. Starkie (2025): op. cit. (note 1), p. 60. The present author was privately consulted concerning this plaquette in email communication with Stefano L’Occaso (November, 2024).

52 For a discussion on Jacob Cornelis Cobaert’s treatment of bronzes see J. Montagu (1996): op. cit. (note 45) and M. Riddick (2017b): A Renowned Pieta by Jacob Cornelis Cobaert. Renbronze.com (accessed February 2025).

53 We may compare, for example, the treatment of this cast against Caesar Targone’s faithful gold repousse example which also faithfully reproduces the details of the original clay model. See examples preserved in the Bode Museum (inv. nos. 2909-14) and at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (inv. 12.135.5).

54 A bronze plaquette of the Downfall of the Giants is autographed on its reverse, FIDIA-f(ecit), by Guglielmo della Porta’s eldest son (Metropolitan Museum of Art, inv. 38.152.13). It is typically thought that Fidias made this cast after breaking into his father’s studio to steal workshop models during the settlement of his father’s estate, but the present author alternatively suggests that this cast was probably made in his youth, perhaps under the tutelage of his father who had hoped his eldest son might adopt the trade of bronze casting. This would explain the proud inscription on the reverse and the rather crude and elementary quality of the cast, indicative of one still learning the trade. It would be self-incriminating for him to brazenly autograph a cast made after a model he wittingly stole without authorization. Although Fidias was found guilty and was sentenced to death for his poor choice of action, that Guglielmo loved, cared, and had high hopes for his eldest son is evinced by early iterations of his will. See Lothar Sickel (2014): Guglielmo della Porta’s Last Will and the Sale of his ‘Passion of Christ’ to Diomede Leoni in Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, vol. 77, pp. 229–39.

55 Davide Gasparotto (2014): The power of invention: Goldsmiths and Disegno in the Renaissance in Donatello, Michelangelo, Cellini. Sculptor’s Drawings from Renaissance Italy. University of Chicago Press, pp. 40-55. See also Michael Riddick (2017c): A Group of Gold Repoussé Reliefs attributable to Cesare Targone. Renbronze.com (accessed February 2025). It is unknown whether Targone produced these during Guglielmo’s lifetime. It is evident Targone was influenced by Guglielmo’s designs and worked with models from his studio. Targone arrived in Rome from Venice ca. 1573-74. As Guglielmo died in January of 1577, his tenure in Gugliemo’s orbit was brief although presumably quite productive given the quantity of works which survive and evince Guglielmo’s influence. Suggesting that Targone was at least active in Guglielmo’s studio or orbit is tacitly implied by Targone’s departure to Florence only a month after Guglielmo’s death.

56 Antonio Gentili is noted as having possessed these models in his studio for a period, having received them from his friend, Bastiano Torrigiani, who had been Guglielmo della Porta’s late assistant and had taken control over the contents of his workshop until Guglielmo’s son and heir, Teodoro della Porta, was given their control upon coming of age. A. Bertolotti (1881): op. cit. (note 48), vol. 2, pp. 120-61. The present author has most recently suggested two silver casts from this series, preserved in the Vatican, may have been executed by Antonio Gentili (Vatican Museums, invs. 65504-05). See M. Riddick (2024): Antonio Gentili da Faenza: Roman Goldsmith of the Renaissance, His Comprehensive Works. Renbronze.com (accessed February 2025). The last known location of the models was their possession, in 1609, by the painter and architect, Giovanni Battista Crescenzi, who by 1617, had moved from Rome to Madrid, Spain. A. Bertolotti (1881), Ibid.

57 This goldsmith is cited during the 1609 trial records of having had a clay ‘Banquet of the Gods’ from this series sometime around 1589-90, presumably Cobaert’s original model, which seems to have been variably loaned to a quantity of goldsmiths throughout the last quarter of the 16th century. A. Bertolotti, Ibid.

58 C.H. Starkie (2025): op. cit. (note 1).

59 The suite of reliquaries—inclusive of ten busts of saints, the arm of a saint, and the leg of a saint—was commissioned by Pope Pius V. Werner Gramberg (1960): Guglielmo della Porta, Coppe Fiamingo und Antonio Gentili da Faenza in Jahrbuch der Hamburger Kunstsammlungen, V, pp. 31-52. See also M. Riddick (2024): op. cit. (note 56).

60 Emmanuel Lamouche (2019): Cesare Targone. Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani – Volume 95. Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana fondata da Giovanni Treccani.

61 M. Riddick (2021): op. cit. (note 2), Appendix B and C.H. Starkie (2025): op. cit. (note 1), pp. 83-84.

62 M. Riddick (2021), Ibid., and M. Riddick (2020): A Possible Corpus, Saint, and Siren by Sebastiano Torrigiani. Renbronze.com (accessed February 2025), see Appendix, pp. 15-16.

63 The present author theorized Juan Bautista Franconio was a German journeyman, probably from Nuremberg, active in the workshop or circle of Bastiano Torrigiani during the early-to-mid 1590s, and that following Torrigaini’s death in 1596, he subsequently sought employment in Seville. M. Riddick (2021), Ibid.

64 A. Bertolotti (1881), op. cit. (note 48), pp. 157-61. Baldo was trained by Torrigiani in bronze casting in 1582 and would later serve as an important assistant to Antonio Gentili da Faenza. M. Riddick (2024): op. cit. (note 56).

65 Andrea and Stefano Tumidei Bacchi (2002): Il Michelangelo incognito: Alessandro Menganti ew la arti a Bologna nell’eta della Controriforma. Edisai SRL, pp. 228-236.

66 R. Coppel (2012): op. cit. (note 39), p. 48.

67 E. Lamouche (2022): op. cit. (note 23), p. 300.

68 J. Montagu (1996): op. cit. (note 45), pp. 35-46.

69 A. Bertolotti (1881): op. cit. (note 48).

70 ‘Un basso rilevo con la passione, e col crocifisso tutto tondo.’ This is reiterated in Anastagi’s records of 1595, noting ‘E adi 25 di aprile (1589) scudi dodici a Rafaello Vaiani gettatore per il bassorilevo di bronzo con la Passione, col Crocifisso tutto tondo di mano di messer Jacomo Fiammingo.’ E. Lamouche (2022): op. cit. (note 23), p. 314 and Annex 4.10, pp. 394-396. This relief was accompanied by another relief, also forming part of this commission, being that of a Pieta provided to Cobaert by Torrigiani in 1585 and presumably that of an ‘expired Christ in the arms of the Virgin,’ originally modeled by Cobaert after Guglielmo’s design, as discussed by the present author in M. Riddick (2017b): op. cit. (note 52). It is worth noting, Torrigiani also shared what is probably this same model of a Pieta, with his friend and fellow Roman silversmith, Antonio Gentili da Faenza, in this same year (1585) for a commission from Francesco de’ Medici. See M. Riddick (2024): op. cit. (note 56), no. 34, pp. 114-15.

71 M. Riddick (2021): op. cit. (note 2), Appendix B.

72 C.H. Starkie (2025): op. cit. (note 1), p. 2; see M. Riddick, Ibid., Appendix B, census nos. 2, 1, 4, 6, and 5, respectively.

73 M. Riddick, Ibid., Appendix B, p. 11, no. 3

74 C.H. Starkie, Email communication (November, 2024).

75 C.H. Starkie (2025): op. cit. (note 1), p. 97.

76 Various Authors (2022): Italian Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY, no. 102, pp. 287-94.

77 See endnote 45.

78 The scale of the tabernacle’s relief panels was altered during successive iterations of changes made to its design over an extended period. See P. Malgouryres (2011): op. cit. (note 45).

79 While it is undetermined how early Torrigiani and Jacopo del Duca may have been acquainted, it is within reason that their paths could have intersected in 1573 or earlier. Torrigiani collaborated with Jacopo’s brother, Lodovico del Duca, in executing the gilt bronze tabernacle for Sta Maria Maggiore in Rome. For this project Lodovico employed the same relief panels as Jacopo earlier used on the tabernacle preserved in Padula. However, Lodovico selected to use Torrigiani’s crucifix model for the feature of Christ, based upon Guglielmo’s design, for the Crucifixion panel on this tabernacle. See J. Montagu (1996): op. cit. (note 45). That the del Duca brothers both depended on Torrigiani for sculpted models of Christ is further emphasized in Jacopo’s marble relief of the Trinity for the Tomb of Cardinal Alessandro Crivelli, ca. 1571-74, which likewise borrows Torrigiani’s model as its point-of-reference and could suggest Jacopo sought models from Torrigiani during this period, thus resulting in his possible exposure to Michelangelo’s model—accessible to Torrigiani via Guglielmo’s workshop—leading up to the beginning of 1574.

80 M. Riddick (2021): op. cit. (note 2), Appendix B, no. 18, pp. 31-33. The facial character of this model appears to reflect that of a corpus preserved at the Casa Museo Ludovico Pogliagh in Varese and another corpus from an unidentified collection which Lorenzo Principi suggests might be the work of Prospero Antichi. See Lorenzo Principi (2024): La “vita postuma” del Crocifisso in bronzo di Prospero Bresciano: da Ludovico del Duca a Paolo Sanquirico, a Pasquale Pasqualini in Gli scultori a Roma nella seconda metà del Cinquecento Circolazione, scambi, modelli. Università di Roma Tre, pp. 81-124, see figs. 31-33.

81 Metropolitan Museum of Art, inv. 44.142.2.

82 Paola Venturelli (2012): Vincenzo I Gonzaga, 1562-1612 – il fasto del potere. Museo Diocesano Francesco Gonzaga, Mantova. No. 69.

83 Museo Civico di Udine, inv. 159. Giuseppe Bergamini (ed.) (1992): Ori e Tesori d’Europa: Mille anni di oreficeria nel Friuli-Venezia Giulia. Electa, Milan, p. 201. With thanks to Lorenzo Principi for providing this reference.

84 For the examples at the Museo Diocesano y Catedralicio in Lugo (Galicia, Spain), Collegio Alberoni in Piacenza, and other important examples in private collections, see L. Principi (2024): op. cit. (note 80).

85 Not published by L. Principi. The location of this example is currently unknown but was published with a suggested attribution to Benvenuto Cellini in Robert Hobart Cust (1910): Burlington Magazine, Volume XVII — April to September and R.H. Cust (1910): The Life of Benvenuto Cellini. 2 vols, G. Bell and Sons, Ltd, London, see frontispiece of vol. 2. With thanks to Olga Majeau for bringing this to my attention (email communication, February 2025).

86 M. Riddick (2020): op. cit. (note 62).

87 The donation and receipt of the altar cross is cited by Ippolito Donesmondi (1625): La vita del venerabile vescovo di Mantova Francesco Gonzaga. See P. Venturelli (2012): op. cit. (note 82).

88 ASDMn Santa Barbara, Inventari, b. 111, “Libro nel sacro Reliquario della Chiesa di S. Barbara de Mantova” 1587-1617, c. 54r. Again, noted in the inventory of 1611: ASDMn, Santa Barbara, Inventari, b. 111, cc. 7v-8r. See P. Venturelli (2012), Ibid.

89 M. Riddick (2020): op. cit. (note 61). Fernando Loffredo rejected this attribution but confoundingly maintained an 18th century French origin for the crucifix despite the present author’s observation of a coeval cast featured on the altar cross preserved at the Museo Diocesano di Mantova which secures a date prior to 1598 and locates the origin of the crucifix in Rome, Italy. Various Authors (2022): op. cit. (note 76), no. 183, pp. 484-85.

90 L. Principi (2024): op. cit. (note 80).

91 Ibid. See also E. Lamouche (2002): op. cit. (note 23), pp. 255-57; and Steven Ostrow (1998): Paolo Sanquirico: a Forgotten Virtuoso of Seicento Rome in Storia dell’arte, no. 92, pp. 27-59.

92 Alessandro Angelini (2012): Il Crocifisso di Prospero Antichi, in Una gemma preziosa. L’Oratorio della Santissima Trinità in Siena e la sua decorazione artistica. Siena, pp. 127-129. The influence of Michelangelo’s model on Prospero Antichi is evident in comparing the differences between the Siena crucifix and that commissioned by Cardinal Savelli in Rome. This is elaborated in L. Principi (2024): op. cit. (note 80).

93 ‘s’era procacciato un Crocifisso di Bronzo di Prospero Bresciano appunto uscito dalla forma, senza che quel gran Maestro ne avesse tagliati i condotti, e per molto, che alcuni ci s’affaticassero, non fu mai possibile il persuaderlo a farglieli tagliare, ed a farlo rinettare, parendo a lui, che nessun’altro avrebbe potuto ciò fare quanto il Maestro ‘ / ‘I had procured a Bronze Crucifix by Prospero Bresciano which had just come out of the mould, without the great Master having cut the pipes, and despite the efforts of some, it was never possible to persuade him to have them cut and to have them cleaned, it seeming to him that no one else could have done this as well as the Master.’ Baldinucci (1702), p. 140. See also L. Principi (2024), Ibid.

94 This idea is supported by L. Principi, Ibid.

95 E. Lamouche (2002): op. cit. (note 23), pp. 262-67.