by Michael Riddick

Preview / download PDF in High Resolution

Originally published in Intagliator di stampe e scultore eccellente. Giovanni Battista Scultori incisore del Cinquecento, ex. cat., Mantova, Palazzo Ducale, 19 April – 21 July 2024

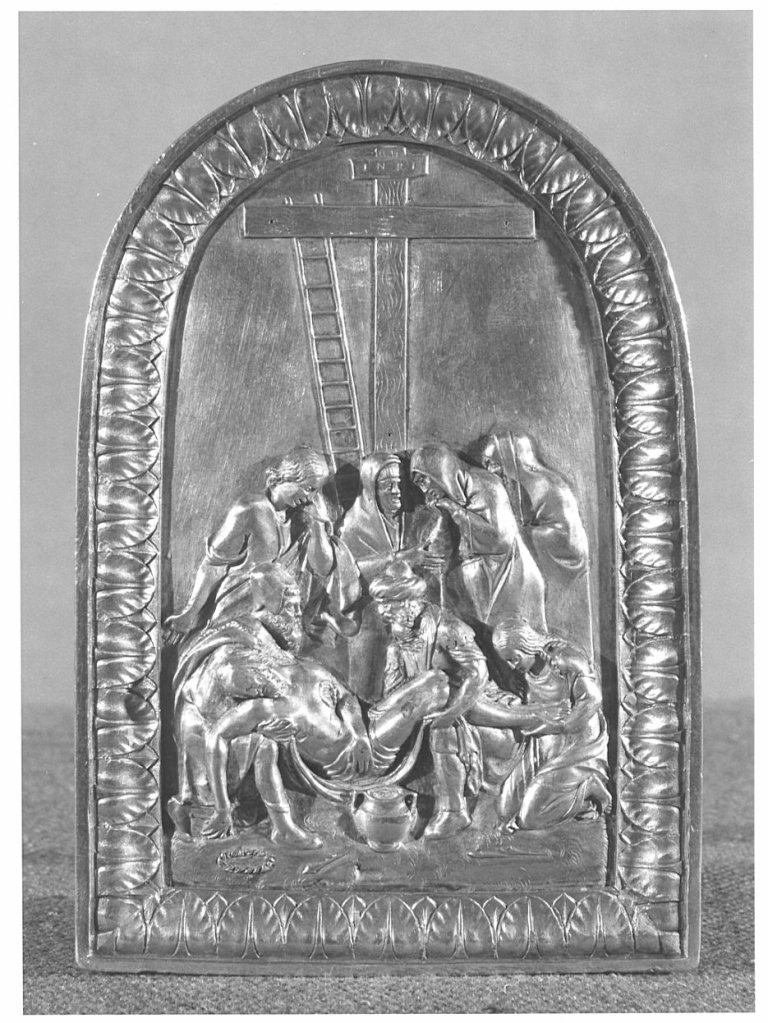

Cover – a bejeweled gilt silver pax of the Lamentation over the Dead Christ by Giovanni Battista Scultori, 1562, Mantua, Italy (Diocesan Museum of Mantua)

Evidence concerning Giovan Battista Scultori’s activity as a goldsmith is limited although we may surmise the ‘great quantity of stones and engraved rings’ his daughter, Diana, inherited after his death, may attest to the possible stock of an active goldsmith.1 However, it is undetermined if these were personal effects acquired over time or a personal workshop inventory.

Scultori’s attendance in witnessing various events precipitating the death of the goldsmith Niccolò Possevini in 1541, and his appointment as guardian of that goldsmith’s children, indicates a developed trust and camaraderie among goldsmiths. Also in attendance were Possevini’s pupils, the Milanese brothers, Giuseppe and Nicolò Cernuschi.2 Scultori’s association with this retinue of goldsmiths could lead us to assume that he learned the art of goldsmithing under the auspices of Possevini and probably alongside the Cernuschi brothers who were very close in age to him.3 The reprise of a certain goldsmith, Giuseppe, operating alongside Scultori in the 1561 preparations for the Duke of Mantua’s approaching wedding to Eleanor of Austria could suggest such an extended collaboration.4 However, this Giuseppe could equally refer to Giuseppe Possevini, Scultori’s godson and the child of the Niccolò who we presume was Scultori’s teacher.

Scultori’s early activity as a stuccatore, and his subsequent practice of engraving, would have suited well for the skills required of a goldsmith and it is perhaps through his exploration of engraving that he naturally evolved into learning this art. The period of his engraved productions may, in fact, partially coincide with his possible training as a goldsmith.

As adjudged by the praise he received, Scultori excelled in the production of crucifixes, although we are uninformed about what kind of crucifixes these were. Stefano L’Occaso’s suggestion that the Giovan Battista responsible for a cross—cited by Vasari—formerly at Verona Cathedral and moved to the Bishop’s Palace, could indicate the production of an altar cross.5 Vasari’s description of the crucifix having been of ‘beautiful relief’ would indeed prompt us to consider it was an altar cross and not a freestanding sculpture.6 Furthermore, Pietro Carnesecchi’s edification of Scultori as ‘the one who makes crucifixes of more excellent relief than any other sculptor of our times,’7 could suggest the same. Altar crosses and processional crosses would have suited well for relief-work, as the finials were often worked in high-relief and the arms executed in low-relief, typically with vegetal motifs contrasting against densely packed engraved striations. A similar handling of such striated features is echoed in the finely engraved horizontal lines Scultori deploys in his articulation of clouds on his pax preserved in the Diocesan Museum of Mantua (cover). However, Scultori’s own description of a silver crucifix he made for Ippolito Capilupi, a ‘cristo grande,’ or ‘large Christ,’ would lead us to assume the work was a fully dimensional sculpture in-the-round.8 We might also diverge to consider that his crucifixes could also refer to bejeweled devotional crosses, like those presumably worn regularly as a necklace by the Mantuan Duchess, Eleonora of Austria, as observed in her painted portraits9 and reflected also in her portrait medal of 1561 by Pastorino de’ Pastorini,10 but this latter idea seems less likely.

Scultori’s recorded activity, extracted in the letters of 1562, suggest an experienced goldsmith having already reached the peak of his career in the production of celebrated crucifixes. He is still active, however, as a stuccatore, evident in his contracted work in 1561 to participate in the production of stuccos and statues for the decorations involved in the wedding event of Guglielmo Gonzaga to Eleonora of Austria.11 Preparations for the event attracted a variety of artists, including the bronzista, Leone Leoni, who seems to have been focused on architectural projects during this period of Gonzaga patronage.12

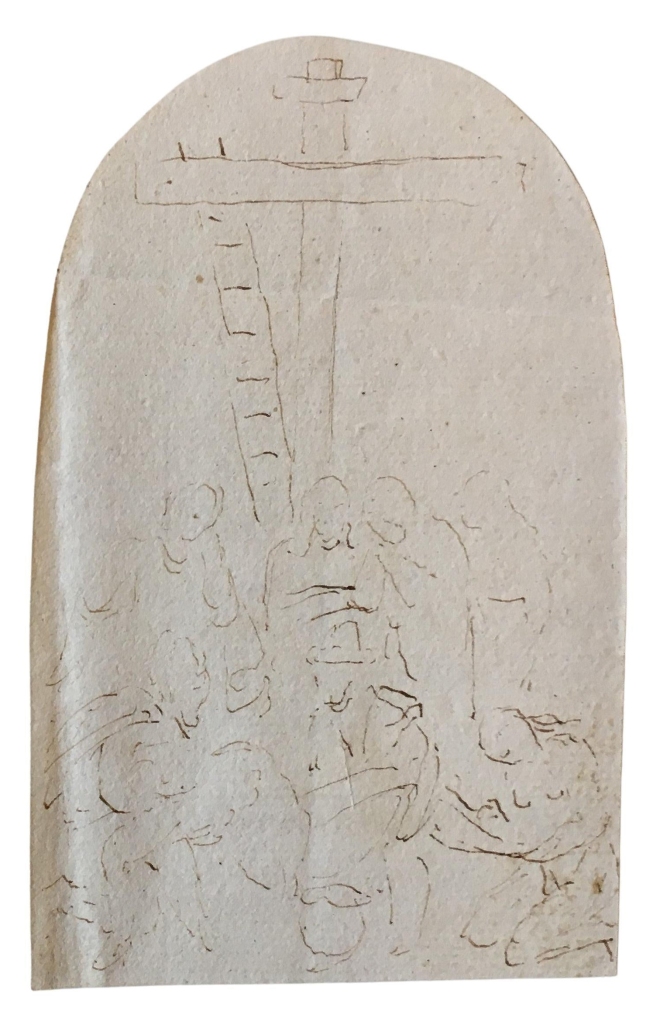

Fig. 1 – Sketch of a pax depicting the Lamentation over the Dead Christ by Giovanni Battista Scultori, 1562 (Mantua State Archive, archive of Capilupi heirs of Mantua, b. 39)

In 1562, Ippolito Capilupi, the apostolic nuncio to Venice, commissioned a silver pax of the Lamentation over the Dead Christ and a silver crucifix from Scultori. The crucifix was to follow after a model of one he had earlier produced for Cardinal Ercole Gonzaga. As delineated in L’Occaso’s review of these documents, Scultori’s crucifix for Cardinal Gonzaga was made before February of 1562 and the new example made for Capilupi weighed about 14 ounces, cost a sum of 40 gold ducats and required four months to complete.13 On 12 June, Scultori informs Capilupi that the crucifix is complete and explains that he has also cast the pax. Attached to his letter was a sketch representing the figural group of his Lamentation scene (fig. 1). Scultori commented that he is ‘working around it,’ and when finished, he can have ‘the ornamental part,’ completed in Mantua.14 These choice words are insightful about the nature of Scultori’s working methods and help explain some details concerning the various incarnations of the pax that survive today, to be discussed.

Scultori’s completion of the pax was followed by a dispute concerning the price to be paid for it and this seems to have been due to a version of the pax Scultori earlier made for the Bishop of Nola, Antonio Scarampi.15 It would seem Capilupi was advised by Scarampi concerning what price to pay for his example of Scultori’s pax, but Scultori was upset about this judgment because he claims to have put double the effort into completing Capilupi’s version of the pax. Scultori also explains he was motivated to put forth this additional effort out of appreciation for Capilupi’s patronage of the silver crucifix, already completed. Amidst this dispute, Scultori’s letter also reveals that the pax for Capilupi appears to have had an earlier origin in an unrealized commission from Bishop Niccolò Ormaneti, with an agreed upon price of 20 gold ducats, apparently never begun.16 It would seem Scultori’s additional efforts in preparing Capilupi’s pax prompted him to judge its final value at 25 gold ducats.

The pax, previously kept at the Sangue di Cristo of the Basilica of Santa Barbara in Mantua (cover), and now preserved at the Francesco Gonzaga Museum (inv. 200), may or may not be the pax commissioned by Capilupi, as we do not know if the pax was ever returned to Scultori or if Capilupi decided to pay the 25 ducats for it. However, it is generally presumed Capilupi rejected the pax and that Scultori probably instead succeeded in selling it to Guglielmo Gonzaga, where it would have likely entered the collections at Santa Barbara.17

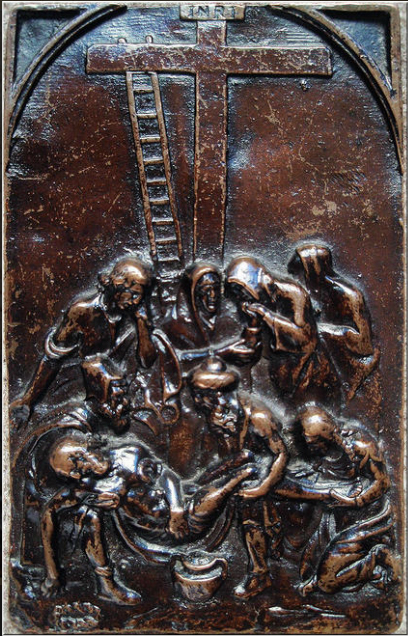

We also do not know if Ormaneti’s commission was ever reignited, but we may discern from this dispute that the example for Scarampi, executed with less effort, must be the previously unnoticed example of Scultori’s Lamentation belonging to the Lodi Cathedral where Scarampi was later appointed as bishop and served until his death on 30 July 1576,18 presumably resulting in the pax entering the cathedral’s treasury (fig. 2).

Fig. 2 – Silver pax of the Lamentation over the Dead Christ by Giovanni Battista Scultori, before 1562 (Lodi Cathedral)

The Lodi pax shares the same impressive qualities as the Mantuan pax, inclusive of a polished matte finish and commensurate fine details like the simple punch representing nail holes featured on the beams of the cross—noticeably crude and wrongly located on later bronze aftercasts—or the finely engraved texture applied to the beams of the cross.

A noticeable distinction between the Mantua and Lodi examples is the degree of finish-work given to the Mantuan example, which includes additional textures like the hem of the standing mourner’s robe striated to imitate fringe, the headgear of Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus, textured with a soft peening of the silver or their respective footwear, textured with a well-controlled punch tool. Also noticeably different is the crown-of-thorns on the ground which is more remarkably articulated on the Mantuan example. The fineness of the Mantua pax is altogether indicative of an advancing refinement above that of the Lodi example. These observations may reasonably lead us to suggest the Mantuan pax is indeed the one made with extra effort on the part of Scultori, and the one originally intended for Capilupi.

Each example of Scultori’s pax features unique finish-work chased into the ground, depicting tufts-of-grass and the treatment of wood grain on the cross, which again, is more sophisticated on the Mantuan pax with its densely packed design. The grain of the wood on the Lodi example is wavier, less dense and the border of the titulus is less sophisticated. The engraved clouds on the Mantuan pax also indicate an added level of detail and finish-work not present on the Lodi cast. They are expertly realized even in Scultori’s late age. We may observe the same technique heavily employed in various engravings by his son, Adam, particularly in the figure scenes he made after Michelangelo’s frescos in the Sistine Chapel. In addition to the unique treatment of the ground, this feature of clouds may reflect Scultori’s words concerning ‘working around’ the central composition.

We can only speculate concerning Scultori’s involvement in making the frame for the Mantuan pax (cover). The drawing suggests Scultori had not yet created it (fig. 1). However, it’s style and consistency of finishing would lead us to assume it is Scultori’s invention. Further evidence of this can be considered in an aftercast of the frame found on a pax at the Chiesa di San Canciano in Venice, to be discussed (fig. 9).19 It would seem Scultori’s comment about adding the ‘ornamental parts’ of the pax could refer to the addition of precious jewels to the frame. For example, we can observe where several jewels were expected to be secured to the pax, probably affixed with a pronged fastener passing through a hole while the red gems were alternatively lowered into a cavity cut into the silver frame, presumably forming part of the stock of a goldsmith’s available inventory and requiring the face of the pax frame to be incised.20 The coloring of the collet settings for the jewels appear independently conceived from the materials used for the pax and this is especially true for the pearls whose unique settings appear worked in precious gold with white enamel embellishments.

We could speculate who may have been responsible for bejeweling the pax, if not accomplished by Scultori himself. L’Occaso suggests the possibility of Giuseppe Cernuschi21 and the present author also suggests either of the two Possevini brothers whom Scultori had been assigned as guardian. We may note Giuseppe Possevini, for example, is registered with the Goldsmiths Guild in Mantua in 1559,22 and just prior to Scultori’s production of the Mantuan pax.

In sum, the production of the Lodi and Mantua paxes is indicative of the use of a workshop model where the primary alterations are found in the distinctions that accompany the finishing process introduced after a relief is cast. That the lower register of the relief was inclined to regular alterations is evinced in Scultori’s sketch of the pax (fig. 1) which omits the lower portion of the relief, inclusive of the crown-of-thorns, which is rendered differently—probably in repoussé—on both examples of Scultori’s pax. These edits are therefore the freehand work of the silversmith in his post-casting production.

The present author identifies fifty-six cast examples of Scultori’s Lamentation within the art market and cultural institutions (see Appendix) and there are surely more examples not yet identified in further collections. A detailed analysis of these examples helps encourage insight in our understanding of the enduring appreciation for Scultori’s Lamentation, how it may have been diffused, and which examples are securely or likely to be the product of his own hand or environment.

While Scultori’s engravings experienced only a modest circulation, his Lamentation proved its relevance over centuries. We cannot say whether it was ever Scultori’s ambition to achieve fame or respect through the seriality of his works in precious metals and prints, but we can ascertain that the Lamentation’s small-scale, plain ground and simple, yet attractive, design lent itself to the possibility of conveniently being edited and reproduced for subsequent generations inclined to devotional works-of-art.

The convenience with which Scultori’s invention could be modified is most exaggerated in an example belonging to Sandro Ubertazzi which reproduces the primary relief set entirely on a new rectangular ground with the addition of modeled trees flanking the scene and two engraved ladders leaning on the cross.23 The production is provincial and is a dramatic late 19th century or early 20th century embellishment of the relief.

Fig. 3 – White metal African devotional trinket box with the Lamentation over the Dead Christ after Giovanni Battista Scultori, 19th-20th century (John Gardiner collection)

Another modern and unique example of Scultori’s Lamentation is observed in a silver or silvered metal cast appropriated into an African charm box (fig. 3), similar to a balangandan, and probably associated with Catholic missions into Africa during the late 19th or early 20th century.24 Lastly, a fine late Rococo pax, dated 1781, at a church in the Diocese of Bologna, proves the lasting liturgical use of Scultori’s design.25

We can suggest Scultori had some interest or awareness of the potential seriality of his designs but this isn’t necessarily unique for a goldsmith whose typical business involved the production of casts in various metals based upon a suite of workshop models, either purchased from others, developed by himself or executed by hired assistants. We can assume by his namesake and participation in the modeling of stucco reliefs, as well as his talents with a burin in the art of engraving, that Scultori had all the requisite talents that go along with the independent production of a goldsmith.

A further example of Scultori’s production of the Lamentation, now lost, may be preserved by two unique bronze aftercasts that appear to descend from a distant finer original produced by Scultori.26 The casts are rectangular and feature integrally cast spandrels above the relief’s arch which reproduce what may have been a contemporaneous setting for the relief; possibly for a cabinet, tabernacle or private altar (fig. 4).27 The cast from a private collection still records, although faintly, the horizontally etched lines we observe in the background treatment of Scultori’s pax in Mantua.

Fig. 4 – Bronze plaquette of the Lamentation over the Dead Christ, after Giovanni Battista Scultori, 16th-17th century (private collection)

A more substantial update to Scultori’s model is observed in a ‘second state’ of the Lamentation known by a minority of bronze aftercasts28 that derive from a finer silver example preserved at the Santa Maria della Ghiara in Reggio Emilia (fig. 5). The framed setting of the pax against a red velvet background surrounded by silver appliques is a 19th century arrangement and the pax does not seem to be noted in any of the basilica’s inventories dated up until 1797 and may have possibly entered its collections sometime thereafter.29

Fig. 5 – Silver pax of the Lamentation over the Dead Christ, after Giovanni Battista Scultori with a frame by another hand, probably Venetian, last quarter of the 16th century (Santa Maria della Ghiara in Reggio Emilia)

This ‘second state’ of Scultori’s Lamentation omits the titulus, lacks the chased delineation between the two beams of the cross, curves the handles of the pot, removes its contents, excises the left-leaning ladder in exchange for a weakly articulated right-leaning ladder and adds a new standing mourner behind the left-most attendant standing behind Joseph of Arimathea. However, these edits to the composition are not due to the producer of the Santa Maria della Ghiara pax, probably made sometime during the last quarter of the 16th century and evidently operating from circulated models that were in that provincial silversmith’s studio. Rather, these manipulations to Scultori’s Lamentation belong to edits probably conceived by Scultori, or an assistant, sometime after 1562.

Fig. 6 – Bronze plaquette of the Lamentation over the Dead Christ, probably by Giovanni Battista Scultori, after 1562 (private collection)

This is suggested by an intermediary and very fine gilt bronze cast recently sold by Coutau-Begarie auction house in Paris (fig. 6).30 The newly added figure is quite prominent in this example, commensurate in high-relief with the other attendants, whereas this figure is otherwise subdued and fading into the background on all other bronze examples of this ‘second state.’ The reason for this is due to the derivation of all aftercasts being descendant of the Santa Maria della Ghiara example, whose inclusion of this figure is weakened on account of a column’s capital belonging to the integral pax frame which intrudes over the figure’s head and required that silversmith to subdue its otherwise dimensional qualities.

The bronze casts using the silver Santa Maria della Ghiara pax as their master model could be due to a provincial workshop active in Emilia Reggio, and quite possibly the Capanni foundry who produced bells and probably other devotional items for churches in that region from the 16th century onwards. X-ray fluorescence testing of one such example at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, features a higher-than-normal concentration of tin and zinc, and suggests it was cast in a late 16th century bell foundry.31 The subtle presence of verdigris on this cast and also that of an exact bronze aftercast of the Santa Maria della Ghiara pax at Massa Fiscaglia are indeed suggestive of such an origin.32

In the present author’s opinion, the Coutau-Begarie example is a production overseen by Scultori, an assistant or one of his children. This ‘second state’ of the relief may have been intentionally prepared to distinguish it for a patron, possibly Bishop Ormaneti, if he decided later to continue his stalled commission of this pax from Scultori, perhaps on occasion of his subsequent assignments as Vicar General of the Church of Milan, or his later installment as the Bishop of Padua in 1570.33

We can observe how the invention of this ‘second state’ required taking an impression of the original model of the figural group. To this was added the cross, now wider; and the ladder, now leaning right; and other minor elements modeled anew, inclusive of the added figure and slightly lengthened ground at the base of the relief. The cross on this example features expertly engraved texture and its gilding suggests it was a commission of some importance. The stylistic character of the newly added figure should lead us to consider further that Scultori was involved in these edits and may have started producing bronze versions of his composition sometime after 1562.

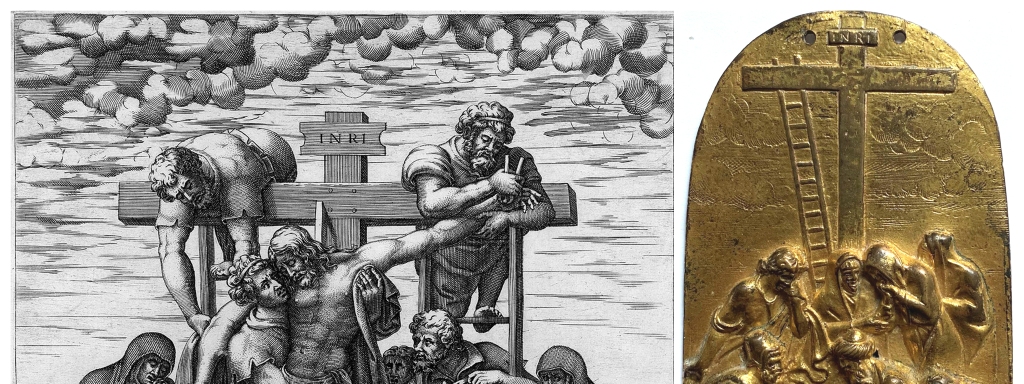

Fig. 7 – Bronze plaquette of the Lamentation over the Dead Christ, probably by Giovanni Battista and Diana Scultori, after 1562 (Luigi A. Buttazzoni collection)

Further confirmation of this idea is found in another gilt bronze example belonging to the collection of Luigi A. Buttazzoni (figs. 7, 8).34 This cast reproduces the original state of Scultori’s Lamentation but instead of featuring the clean horizontally engraved clouds we observe on the Mantuan pax, we instead have a treatment that almost precisely recalls the clouds featured on Diana Scultori’s print of the Descent from the Cross (fig. 8), executed after her father’s design.

Notable are the distinctive feature of interrupted horizontally stroked lines that envelope the upper body and heads of the scene’s protagonists and terminating upward into cotton ball-like clouds that are variably hatched to suggest shadow and contrast. The engraved features indicate a developing but confident artist capable with a burin (fig. 8). This engraved afterwork appears to precede the applied gilding but must post cede the chasing of the bronze which has been executed by a cruder tool or a less capable finisher employed in the foundry responsible for its casting. This is most apparent in the hard line, forming a stroke, around the right-most standing attendant of the scene and in some of the treatment around the cross as well as the inscription on the titulus. We can imagine this production involved a variety of individuals inclusive of a founder, finisher, engraver (Diana?) and then a gilder. It is challenging to say how this cast was used. The holes seem to suggest some form of possible suspension or mounting.35 If treated by Diana, we could assume the dating of this cast is commensurate with her early period of activity while still learning under her father’s instruction and in near coincidence with her print of the Descent, possibly realized during the late 1560s.36

Fig. 8 – Detail of Diana Scultori’s print of the Descent from the Cross, late 1560s (right; Nicolaas Teeuwisse collection); detail of a bronze plaquette of the Lamentation over the Dead Christ, probably by Giovanni Battista and Diana Scultori, after 1562 (right; Luigi A. Buttazzoni collection)

The presence of these possibly contemporaneous bronze casts of Scultori’s Lamentation may be due to an interest in expanding his patronage through a less precious material. We observe how Scultori protested about money when he was offered a weak price for the pax he executed for Capilupi and requested for it to be returned so he could sell it for twice the proposed sum.37 He may have also considered the reproductive power of bronze, operating in an environment where previous masters like Pier Jacopo Alari Bonacolsi (called Antico) and Galeazzo Mondella (called Moderno) thrived in the execution of bronzes. While it seems less likely Scultori would have cast these himself, instead relying on a regional foundry, he certainly would have been familiar with the preparations and requirements involved in casting bronze, attested by his earlier work on the lost eucharistic tabernacle for the Cathedral of Verona in which he provided the sculpted models and casting moulds to a certain bronze founder named Lucca38 as well as his involvement in producing the bronze angels for the tornacoro, formerly in the same Verona Cathedral and reasonably attributed to Scultori.39 His experience working with bronze founders on these projects could anticipate his collaboration with a founder during this late period of his career. A possible candidate could be a figure like Timoteo Refato,40 an Augustinian monk and medallist who preferred working in small-format sculpture and cast his own productions, as evinced in a quantity of small lead figures he produced for Ulisse Aldrovandi when visiting him in Bologna in 1570.41 Prior to this, Refato was active in Mantua throughout the 1560s; the period in which we surmise Scultori began producing bronze examples of his Lamentation. Scultori’s documented interest in collecting medals may also have put him in Refato’s orbit.42 Refato would also later produce bronze portrait medals of Diana Scultori and her husband, Francesco Cipriani (called Volterrano), in Rome around 1575 and possibly on occasion of her acceptance into the artistic, religious and social confraternity, I Virtuosi al Pantheon, to which her husband and brother were already privy.43 The connection between Refato and Scultori are thus worthy of some consideration in regard to the production of the contemporaneous bronze casts we identify in this survey.

It is through the serial quality of bronze that we know Scultori’s composition well, even if his name was only recently associated with the Lamentation relief in plaquette literature during the last quarter of the 20th century.44 While a minority of the various identified casts are unique outliers, predominantly modern incarnations, a majority of them can be organized into at least four unique groups that suggest the output of four individual productions responsible for their diffusion, one of which, we suggest occurred already in the area of Emilia Reggio at an early date.

A group of further old casts are identifiable by a gilt silver example at the Accademia Carrara45 and bronze examples at the Museo Correr,46 Museo Nacional de Artes Decorativas in Madrid, one in an unidentified church in Florence (displayed in a later arched ebony wood frame),47 an example with Mario Scaglia48 and one offered by Cambi auction house.49 The Correr example previously belonged to Emmanuele Cicogna who could have acquired his example as early as the 1810’s, thus providing a general terminus ante quem for their production. These casts are identifiable by the less refined INRI etched into the titulus which curves slightly upward. The upper beam of the cross is separated from the vertical beam with naively chased lines and the ladder features punched divets flanking each rung. These examples are especially identifiable by the introduction of texture to the garb on two of the figures: the fluting on the cap of Joseph of Arimathea and the horizontal strokes on the shawl of the right-most standing mourner.

A further production—evidently deriving from a relative of the aforenoted group—appear to all descend possibly from the same foundry and must be relatively modern casts, but produced before 1885, adjudged by the provenance of an example at the Hermitage in St. Petersburg.50 They are comprised of a brassy metal and extremely dark patina. The chief identifiers of this edition include the very modern incised INRI along the titulus, the slightly incuse reverses along the lower portion of the reliefs and the overall waxy surface quality of the casts.

Another group of probable 19th century casts include the rectangular variants formerly with Eugenio Imbert51 and one from a recent Pandolfini auction.52 These examples feature evenly filed edges and an unusual grainy and pitted surface texture. They may have been intended to be set into frames.

Fig. 9 – Silver and parcel gilt pax of the Lamentation over the Dead Christ, after Giovanni Battista Scultori, probably Venetian, last quarter of the 16th century (Chiesa di San Canciano, Venice)

Also worthy of discussion is a unique parcel gilt pax of Scultori’s Lamentation set within a late Mannerist frame at the Chiesa di San Canciano in Venice, previously noted (fig. 9).53 This silver pax is not by Scultori but it indicates an artist with probable access to Scultori’s original models. This is most apparent by the manner in which the pax is assembled. It does not appear to be a common aftercast where we would typically observe a frame cast integrally with its relief. Rather, the central scene is an independent plaquette, as well as its surrounding frame and the other elements that comprise its architectural setting. This would suggest the maker of the San Canciano pax had direct access to Scultori’s models either while Scultori was alive or shortly after his death. The pax closely follows the format of the Mantuan pax but exchanges a plain ground beset with jewels for a flanking parcel gilt figural motif. The eucharistic applique atop the pax could inform us that the Mantuan pax likewise had this same feature, now lost, as indicated by the hole at the top where it would have been affixed.

The maker of the San Canciano pax appears to have put a Venetian twist on Scultori’s otherwise Mantuan invention, with the alternative engraved rendering of the clouds, roughly hammered ground and feature of highly Mannerist figures placed in niches enclosed by scrolling cartouches. However, an origin in Mantua still cannot be ruled out. We might wonder if Scultori sold his moulds to a local or Venetian silversmith to raise funds or if his children sold his moulds following his death. We could assume the moulds for the frame of the Mantuan pax would have also transferred, having been the property of Scultori by way of his own hand or that of a hired assistant.

The San Canciano pax could date during the 1570’s, adjudged by a dated Venetian pax of 1576 featuring the same silver pediment relief of God the Father, albeit in slightly cruder form than our example here.54 This pediment model remained in use into the first decade of the 17th century adjudged by its feature on another dated pax of 1609, also in Venice.55 Based on the quality of the pediment relief on the San Canciano pax, as well as its flanking figures, we can assume the silversmith responsible for this production may have been one of the more important or well networked silversmiths presumably active in Venice during this period. Scultori’s ties to Venice through his documented visit there in 154456 or his work for the Venetian nuncio apostolico, Capilupi, introduce possibilities concerning the diffusion of his creations in that city. We may alternatively consider the presence of Venetian goldsmiths in Mantua who could have acquired his models, like a certain Domenico di Mafei, present in Mantua in 1576, just after Scultori’s death.57

An awareness of Scultori’s composition appears to have possibly traveled to nearby Cremona at an early date. Francesco Rossi first commented on the Lamentation’s dependence on Parmigianesque models, primarily in the Cremona region and although post-dating Scultori’s pax, Rossi noted a related Pietà with Saint Catherine by Bernardino Campi, painted in 1572,58 whose composition closely echoed Scultori’s pax while Attilio Troncavini has more recently cited a possibly earlier study for Campi’s creation preserved in the British Royal Collections.59 Troncavini also commented on further analogies with a Lamentation by Campi, executed in 157560 and the relationship of these works would suggest a burgeoning awareness of Scultori’s production beyond Mantua as early as the 1570s.

While many of the bronze aftercasts descending from Scultori’s original silver relief show only a thoughtfully organized arrangement of figures in high-relief, the true power of Scultori’s creation is observed in the fine Lodi and Mantuan paxes in which the emotive power of the relief is carried by the expressiveness of the actors whose features are, at once, soft yet engaging. The greatest degree of liveliness in this small sculpture is captured in Scultori’s remarkable portrayal of the tacit communication between Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus, who look upon one another with the intense responsibility of lifting the savior of the world with utmost care, strength and determination. We can imagine the immediate action about to unfold while the mourning Mary gazes in disbelief, still holding the feet of Christ.

In light of the many reproductions of Scultori’s Lamentation which survive in the medium of bronze, we may look to other works in the field of plaquette studies that might help reveal other preservations of Scultori’s productions. To date, only Jeremy Warren has put forth some reasonable suggestions,61 notably a gilt bronze art market pax originally considered a possible production of Nicolò Roccatagliata.62 While there are superficial characteristics that would prompt us to connect this production with Scultori, the overall work seems to be a Venetian production of the late 16th or early 17th century. Somewhat informative of this is the separately applied engraved silver backing typical of Venetian paxes and the presence of a presumably unpublished earlier silver repoussé example of the central composition—in which the Pietá scene is flanked by a standing Joseph of Arimathea and kneeling Mary—in the collections of the Palais des Beaux Arts in Lille, France, and considered a Venetian production of the 1590s. This finer silver original in Lille, whose execution is awkwardly realized and weakly managed, unfortunately lacks any firm connection with Scultori’s Lamentation.63

Warren has also suggested a rare plaquette of the Deposition as the possible work of Scultori.64 Certain compositional and stylistic analogies make this idea enticing although, its lower relief, slightly different style and exaggerated Mannerist tendencies would suggest a different hand, although one perhaps not far from Scultori’s orbit and worthy of further exploration.

While these ambitious first attempts at locating Scultori’s productions in the sea of yet-to-be-identified artworks is a good first step toward a progressive understanding of Scultori’s silversmith production, we can only hope more stimulating works come to our awareness, or anticipate one of Scultori’s long lost, yet admired, silver crucifixes emerge from an unexplored inventory or collection. What is certainly evident is the diverse array of mediums explored by Scultori over his lifetime, and foremost the talent of his sculptural powers brought to bear in the execution of a small work in silver that has stood the test of time, reminding us in the words of Giovan Battista Bertani, who exclaimed, in the execution of figures Scultori had “no equal in all of Italy.”65

Appendix:

SILVER EXAMPLES BY

GIOVANNI BATTISTA SCULTORI

- Museo Diocesano Mantua, Francesco Gonzaga Museum

- Lodi Cathedral

BRONZE EXAMPLES HERE

ATTRIBUTED TO GIOVANNI BATTISTA SCULTORI

- Buttazzoni, Luigi A. (private collection)66

- Coutau-Begarie auction, 28 May 2021, lot 114

NOTEWORTHY EXAMPLES

- Chiesa di San Canciano67

- Accademia Carrara, Bergamo (inv. Bronzi 117)68

- Santa Maria della Ghiara, Reggio Emilia69

MUSEUM COLLECTIONS

- AD&A Museum, Santa Barbara (inv. 1964.534)70

- Ashmolean Museum (inv. WA 1888.CDEF.B665)71

- Berlin Museums (inv. 1680)72

- British Museum73

- Hermitage Museum, Russia (inv. E17505)74

- Hood Museum, Dartmouth University (inv. 2016.64.107) (two examples)75

- Musei Civici Vicenza76

- Museo Civico Medioevale, Arezzo77

- Museo Correr, Venice (inv. Cl. XI.234)78

- Museo Nacional de Artes Decorativas, Madrid

- Museo Stibbert, Florence (inv. 11815)79

- National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC (inv. 1942.9.258)80

- National Gallery of Victoria, Australia

- Tiroler Landesmuseum Ferdinandeum (inv. B69)81

- Warsaw National Museum82

SACRED INSTITUTIONS

- Museo Diocesano di Santo Stefano al Ponte, Florence83

- Certosa di S. Lorenzo al Monte, Florence84

- Unidentified location in the Diocese di Bologna85

- Massa Fiscaglia, Province of Ferrara

- Vatican Museums (inv. MV 64127.0.0)

PRIVATE COLLECTIONS

- Brudniak, Matthew86

- Elkan, Theodor87

- Gardiner, John88

- Goodman, Neil89

- Heinrici, Georg90

- Humphris, Cyril91

- Imbert, Eugenio92

- Löbbecke, Arthur93

- Parpart, Friedrich von (two examples)94

- Riddick, Michael95

- Salber, Dr. Wilhelm96

- Scaglia, Mario97

- Struble, Amy98

- Ubertazzi, Sandro99

ART MARKET

- Arcadia Aste, Italy, 20 March 2018, lot 348

- Artemide Aste, Italy, 19 March 2016, lot 306

- Astarte Aste, Italy, 9 May 2005, lot 368.d

- Baldwins auction, UK, 7 May 2014100

- Cambi casa d’aste, Italy, 3 May 2016, lot 103

- Drouot, Paris, 25 May 1998, lot 1294

- eBay 2019

- Finarte, Milan, 20 March 1997, lot 38b (offered in a previous sale as lot 58)

- Gorringes auction, UK, December 2017, part lot 300

- Koller auktionen, Germany, 30 March 2009, part lot 345d

- Pandolfini, Italy, 19 October 2021, lot 89

- Spink auction, UK, 24 January 2008, lot 71101

- Schuler auction, 8 December 2014, lot 7766

Endnotes:

1 ‘…magna quantitate lapidum, anullorum incisorum…’ Guido Rebecchini, Sculture e scultori nella Mantova di Giulio Romano. 2. Giovan Battista Scultori e il monumento di Girolamo Andreasi (con una precisazione per Prospero Clemente) in Prospettiva, 110-111, 2003, pp. 130-139.

2 For these various references in the Mantuan archives and elsewhere see Stefano L’Occaso, Giovan Battista Scultori, “più eccellente che nissuno altro.” Un protagonista del Cinquecento e le incisioni siglate IBM in “Intagliator di stampe e scultore eccellente.” Giovanni Battista Scultori incisore del Cinquecento, catalogo della mostra (Mantova, Palazzo Ducale, 19 aprile – 21 luglio 2024), Milano, Electa, 2024.

3 Giuseppe Cernuschi, for example, was within a year or two of Scultori’s age. Also in proximity with Scultori is a certain Nicolò da Milano, who worked as a stuccatore alongside Scultori at Palazzo Te, whom L’Occaso also suggests could be Nicolò Possevini and we might also consider that this could be Nicolò Cernuschi from Milan. We could consider the possibility that if Nicolò Cernuschi and Scultori both worked in tandem as stuccatores, they may have also adventured into the art of goldsmithing in tandem. L’Occaso has pointed out, however, Marco Campigli’s recent suggestion this could also refer to Nicolò da Corte. See Marco Campigli, Mantova prima di Genova. Per gli inizi di Nicolò da Corte, in Lo stucco nell’età della Maniera: cantieri, maestranze, modelli, 2021, pp. 35-46.

4 G. Rebecchini (2003): op. cit. (note 1), p. 134. See also S. L’Occaso (2024): op. cit. (note 2), footnote 88.

5 S. L’Occaso, ibid.

6 ‘…crucifillò di rilieuo bellifsimo…’ in Giorgio Vasari, Le vite de’ piu eccellenti pittori scultori e architettori, 1568, vol. 3, p. 250.

7 ‘…quello che fa crocifissi di rilievo più eccellente che nissuno altro scultore di tempi nostril.’ Massimo Firpo and Dario Marcatto, I processi inquisitoriali di Pietro Carnesecchi (1557-1567), ed. critica, Città del Vaticano 1998, II, tomo 3, pp. 1053-54; Maria Teresa Franco, Un eretico in laguna. Giovan Battista Scultori e il refettorio per i canonici di San Salvador. Nuove ipotesi attributive, in Il tempo e la rosa. Scritti di storia dell’arte in onore di Loredana Olivato, a cura di P. Artoni, E.M. Dal Pozzolo, M. Molteni, A. Zamperini, Treviso 2013, pp. 248-253; Gianni Nigrelli, Per Fermo Ghisoni e Giovan Battista Scultori a Venezia. Un nuovo documento e una rilettura per la decorazione del refettorio di San Salvador, in Civiltà Mantovana, LI, 142, 2016, pp. 19-33.

8 Stefano L’Occaso, Committenza e collezionismo della famiglia Capilupi in La famiglia Capilupi di Mantova: vicende millenarie di un nobile casato (secoli 11.-20.), 2018, Accademia nazionale Virgiliana, pp. 219-55.

9 See for example, Kunsthistoriches, Vienna, inv. Gemäldegalerie, 3998.

10 See for example, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, inv. 1957.14.919.

11 Andrea Arrivabene, I Grandi apparati, le giostre, l’imprese, e i trionfi, fatti nella citta di Mantoua, nelle nozze dell’illustrissimo & eccellentissimo signor duca di Mantoua, marchese di Monferrato &c. Con tutt’il successo dell’entrata di sua altezza A. A., 1561.

12 Kelley Helmstutler di Dio, Leone Leoni and the Status of the Artist at the End of the Renaissance, 2011, Routledge Press.

13 S. L’Occaso (2024): op. cit. (note 2).

14 ‘Poi io ho getato una pace et io li son dietro a lavorarla et mando la misura in carta de la sua grandeza, cioè tutto il campo de le figure et quando sarà finita et che piacia a Vostra Signoria Reverendissima si li poterà farli far lo adornamento in Mantoa et io ne pigliarò la cura a ciò quella sia ben servita.’ | I’ve cast a pax and I am working around it and I send a paper with its size, that is the space occupied by figures, and when it’s over, if Your Reverend Lordship desires, I can have the ornamental part made in Mantua and I’ll provide you are well served about it. Translation courtesy of S. L’Occaso, email communication, 2024.

15 S. L’Occaso (2024): op. cit. (note 2).

16 The bishop, also of Veronese origin, was at-this-time the first archpriest of Bovolone in Verona.

17 S. L’Occasso, email communication, 2024. While it is generally believed Duke Guglielmo Gonzaga donated the pax to Santa Barbara, Paola Venturelli notes that the list drawn-up in 1611, of the duke’s precious objects given to the basilica, does not list this object. Paola Venturelli, Ori et Avori, Museo Diocesano Francesco Gonzaga, 2012, no. 8. Nonetheless, this does not dissuade from the possibility as noted most recently in Stefano Savoia, Oreficerie e Argenterie in Una Chiesa per il Principe – La Basilica Palatina di Santa Barbara in Mantova. Libreria Musicale Italiana, 2024, p. 135.

18 Henry Biaudet, Les Nonciatures permanentes, jusqu’en 1648, 1910, B. II, p. 286.

19 The San Canciano pax makes use of Scultori’s original models, sans it’s bejeweled features, for example.

20 We may note, however, some of the jewels must be a 19th century restoration and we do not know if these incisions could be the result of such a restoration. Paola Venturelli observed in the Santa Barbara inventories of 1837 and 1865 that three gems were missing from the pax and must have since been replaced. P. Venturelli (2012): op. cit. (note 17).

21 S. L’Occaso (2024): op. cit. (note 2).

22 Paola Venturelli, Gli statuti dell’arte degli orefici di Mantova (1310-1694), 2008, p. 50.

23 Email communication, 2017, his inv. 137

.

24 John Gardiner collection, South Africa. Email communication, 2017.

25 catalogo.beniculturali.it – Codice di catalogo nazionale: 0800004849 (accessed 2015). Inscribed along its double-footed base: GIUSEPPE PERETI PRIORE DONO I ANNO 1781, apparently donated by the Prior, Giuseppe Perete in 1781.

26 An art market example, formerly in the Neil Goodman collection and sold recently at Spink, London, 8 September 2023, lot 102 and an example preserved at the National Museum of Warsaw, published in: Maria Stahr, Plakiety renesansowe: Muzeum Narodowe w Poznaniu. Poznań, no. 104, pp. 102-03.

27 Francesco Rossi’s census of casts cites this version as his Variant B in Francesco Rossi, La Collezione Mario Scaglia – Placchette, Vols. I-III. Lubrina Editore, Bergamo, 2011, no. IX.20, pp. 383-84.

28 An exact replica of this silver pax, inclusive of its separately cast mid-16th century Venetian frame, is preserved by a bronze aftercast at Massa Fiscaglia in the province of Ferrara (brought to my attention by S. L’Occaso, email communication, 2024). Casts of only Scultori’s central relief in this ‘second state’ are known by examples formerly in the Friedrich von Parpart collection (Rudolph Lepke auction, 18-22 March 1912), the British Museum (inv. 1915, 5-4,12), the Berlin Museums (inv. 1680, published in Wilhelm von Bode, Beschreibung der Bildwerke der Christlichen Epochen: Die Italienischen Bronzen. Berlin, Germany: Konigliche Museen zu Berlin, 1904, no. 1293, pl. LXXIII, p. 124.) and the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC (inv. 1942.9.258). A further art market example (Spink auction, UK, 24 January 2008, Lot 71) features an alternative treatment for the clouds—Venetian in essence—inferring its continued diffusion in-or-around that city. This ‘second state’ is noted in more recent plaquette literature and is referred to as “Variant D” in Rossi’s census of casts published in F. Rossi, ibid.

29 Inv. 69, published in Il santuario della Madonna della Ghiara a Reggio Emilia, a cura di A. Bacchi, M. Mussini, Reggio Emilia, 1996, pp. 280-281, no. 11. The notion that this pax is of the early 16th century and was adopted by Scultori is unlikely, adjudged by the evidence of Scultori’s letter and drawing of 1562 and on account of the paternity of the frame, of probable Venetian origin. The frame is variably used in association with other unrelated plaquette reliefs, see for example Civic Museum of La Spezia (inv. Bp.47), National Gallery of Art, Washington DC (inv. 1942.9.273), Berlin collections (inv. 1368), et al. Douglas Lewis suggested this pax frame could be Venetian in origin, agreed upon also by the present author. The maker of the Santa Maria della Ghiara pax has modified the original form of the frame which would normally feature an entablature separating a rectangular relief scene below and a lunette relief scene above. In order to appropriate Scultori’s arched composition to this frame, the maker has altogether excised the entablature. Lewis’ comments on this pax frame are noted in Douglas Lewis (2017): The Holy Women at the Tomb, no. 423, inv. 1957.14.534 (unpublished manuscript, accessed February 2021, with thanks to Anne Halpern, Department of Curatorial Records and Files): Systematic Catalogue of the Collections, Renaissance Plaquettes. National Gallery of Art, Washington DC. Trustees of the National Gallery of Art.

30 Coutau-Begarie auction, 28 May 2021, lot 114.

31 The plaquette is comprised of 84% copper, 6% zinc, 6% tin and trace elements of lead, iron, nickel, silver, antimony and arsenic. Douglas Lewis (2017): Descent from the Cross, no. 494, inv. 1942.9.258 (unpublished manuscript, accessed February 2024, with thanks to Margaret Doyle, Department of Curatorial Records and Files): Systematic Catalogue of the Collections, Renaissance Plaquettes. National Gallery of Art, Washington DC. Trustees of the National Gallery of Art.

32 See footnote 28.

33 H. Biaudet (1910): op. cit. (note 18), p. 277.

34 Email communication, 2015. His inventory no. 4. The plaquette was formerly in the collection of Vladimir Cicognani, published in Antonella Huber, Un mondo tra le mani: bronzi e placchette della Collezione Cicognani, Bononia University Press, 2012, no. 7, p. 13.

35 A small hole behind the turban of Nicodemus is a minor casting flaw and probably does not relate to how it may have been mounted.

36 Paolo Bellini, L’opera incisa di Adamo e Diana Scultori, Neri Pozza, Vicenza, 1991.

37 S. L’Occaso (2024): op. cit. (note 2). Scultori exclaims he is poor and has a family to support. ‘…perché son pover homo et cargo de famiglia…’

38 Maria Teresa Franco, Uno scultore eretico al servizio di un vescovo santo e pio: Giovan Battista Scultori e l’altare degli angeli per la cappella grande del duomo di Verona in Giulio Romano: Pittore, architetto, artista universal, Accademia Nazionale di San Luca complesso Museale Palazzo Ducale di Mantova, 2021, pp. 365-372.

39 Ibid.

40 The association of Timoteo Refato with medals monogrammed TR was long dismissed on account of George Francis Hill’s discussion of them, however, Attilio Troncavani has recently made a convincing case that the author of the medallist signing TR is indeed the Mantuan Timoteo Refato. See G.F. Hill, Timotheus Refatus of Mantua and the Medallist ‘TR’, in The Numismatic Chronicle and Journal of the Numismatic Society, s. IV, 2, 1902, pp. 55-61 and Attilio Troncavini, Il monogrammista T.R. ovvero Timoteo Refato (o Refati), medaglista e altro, December 2022, AntiquaNuovaSerie.it (accessed February 2024).

41 Giuseppe Olmi, Osservazione della natura e raffigurazione in Ulisse Aldrovandi (1522-1605), in Annali dell’Istituto storico italo-germanico in Trento, n. 3, 1977, pp. 105-181.

42 In the Historiae Imperatorum published in 1563, Hubert Goltzius mentions some Mantua collectors and lovers of ancient medals and coins: among these «loannes Baptista, Sculptor». S. L’Occaso, with the collaboration of A. Mei, Note storico-artistiche sull’altare nella sagrestia della Basilica di Santa Barbara in Mantova in La sagrestia della Basilica di Santa Barbara in Mantova. Interventi di restauro, Mantova 2014, pp. 12-43: 24.

43 Hilary Letwin, “Old in Substance and New in Manner”: the Scultori and Ghisi Engraving Enterprise in Sixteenth-Century Mantua and Beyond, PhD. Thesis, 2013, Johns Hopkins University, pp. 172-73.

44 Giambattista Intra first noted the 1562 letter citing Capilupi’s commission of the pax from Scultori in Giambattista Intra, Di Ippolito Capilupi e del suo tempo in Archivio Storico Lombardo», II serie, 10, 1893, pp. 76-142. The earliest association of the plaquette with Scultori is tentatively suggested by Francesco Rossi, Il medagliere: Associazione Amici dell’Accademia Carrara, Bergamo, 1985, 14, no. 7; and maintained recently in 2011 in F. Rossi (2011): op.cit. (note 27). Jeremy Warren followed Rossi’s attribution with a confident ascription to Scultori in J. Warren, Medieval and Renaissance Sculpture in the Ashmolean Museum, vol. 3, Plaquettes, London, 2014, no. 348, pp. 892-94; and Daniela Ferrari’s discovery of Scultori’s drawing is confirmation of his authorship, published by S. L’Occaso (2018): op. cit. (note 8).

45 Inv. 2006 AC Soprammobili 00222, donated to the Academy in 1983 by Stefano Scaglia (brother of Mario Scaglia who also owns an example of this type, see footnote 27). Francesco Rossi’s earlier suggestion of this example as the possible prototype for the subsequent bronze aftercasts of this version seems plausible. F. Rossi (2011): op.cit. (note 27). With thanks to Giulia Zaccariotto for providing additional information concerning this object (email communication, 2024).

46 Museo Correr, Venice, inv. Cl. XI.234.

47 beweb.chiesacattolica.it (search ‘Deposizione’ in the Diocesi di Firenze).

Possibly located at the Certosa del Galluzzo.

48 F. Rossi (2011): op.cit. (note 27). Acquired at Sotheby’s, London, 7 December 1995.

49 Cambi casa d’aste, 3 May 2016, lot 103.

50 Marina Lopato, Zapadnoevropeiskie Plaketki XV–XVII vekov v sobranii ermitazha. Katalog vystavki, 1976, no. 53, p. 32.

51 Guiseppe Morazzoni, Le placchette italiane. Secolo XV–XIX, 1941, p. 63, no. 165, pl. 34.

52 Pandolfini, 19 October 2021, lot 89.

53 Marino Gallina informs us that the bishop featured on the right of the pax does not represent Saint Canciano and suggests the pax may have come from another church in Venice (email communication via S. L’Occaso, 2024).

54 Prunier auction, Paris, 25 September 2019, lot 33.

55 This dated pax, featuring a silver relief of Christ raised from the tomb with attendant angels, is located at an unidentified church within the Diocese of Venice.

56 G. Rebecchini (2003): op. cit. (note 1), p. 138, his footnote 23.

57 Suggested by S. L’Occaso (email communication, 2024).

58 The painting is located at the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan. F. Rossi (2011): op. cit. (note 27).

59 Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 990124. Attilio Troncavini, Diana Scultori “incisora”, notizie riguardanti il padre Giovanni Battista e alcuni artisti “misteriosi”, November 2022, AntiquaNuovaSerie.it (accessed February 2024).

60 Ibid. Located at the Chiesa di S. Maria della Croce, Crema.

61 See footnote 44.

62 Tomasso Brothers Fine Art, Scultura III, 2010, Paul Holberton Publishing, no. 12, pp. 46-47. Previously sold at Koller auction, 18 September 2008, lot 1005.

63 The figures on the frame of the pax, however, seem to have a potential stylistic relationship with the repoussé figures on the Ghisi Shield, dated 1554, although the extent of Ghisi’s involvement in producing this shield, other than its damascening, remains undetermined.

64 The best-known example is at the British Museum (inv. PE 1915,1216.193), another was in the collection of Neil Goodman (Spink auction, 8 September 2023, lot 133) and the present author locates two further examples at the Museo Bottacin and one formerly with Stefano Bardini (sold in New York, 1918, lot 221).

65 ‘…per conto delle figure messer Giovan Battista Scultore è mirabile e per giuditio mio e non ha pari in tutta Italia per far simil lavori…’ G. Rebecchini (2003): op. cit. (note 1).

66 See footnote 34.

67 A parcel gilt silver cast indicating a possible use of Scultori’s original workshop models. Originally brought to my attention in 2020 by Delia Scheffer, research assistant at the Tyrolean State Museums and located recently by S. L’Occaso.

68 A gilt silver example and possible prototype for a quantity of later bronze aftercasts. See footnote 44.

69 See footnote 29.

70 Ulrich Middeldorf, Medals and Plaquettes from the Sigmund Morgenroth Collection, Chicago, 1944, no. 341, p. 48.

71 J. Warren (2014): op. cit. (note 44).

72 See footnote 28.

73 See footnote 28.

74 See footnote 50.

75 Roger Arvid Anderson, The Roger Arvid Anderson Collection, Medals, Medallions, Plaquettes and Small Reliefs, Paintings, Sculpture, Works on Paper and Textiles, San Francisco: Roger Arvid Anderson (published privately), 2015, p. 187. Previously published in Trinity Fine Art, An Exhibition of Old Master Drawings and European Works of Art, New York: Newhouse Galleries [in conjunction with Trinity Fine Arts Ltd., London, England], catalogue no. 63, 1995, p. 126. A second example, not yet registered, has also been donated to the Hood Museum by Roger Arvid Anderson, previously with the collection of Matthew Brudniak.

76 Davide Banzato, Maria Beltramini and Davide Gasporotto, Placchette, bronzetti e cristalli incisi dei Musei Civici di Vicenza. Secoli XV- XVIII, Vicenza, Palazzo Chiericati, 1997, no. 93.

77 Fiorenza Vannel and Giuseppe Toderi, Medaglie Italiane del Museo Nazionale del Bargello, 2 vols., vol. 1, no. 71.

78 See footnote 46.

79 Giuseppe Cantelli, Il Museo Stibbert a Firenze, Catalogo, 2 vols., II, 1974, no. 879, pl. 181.

80 See footnotes 28 and 31.

81 Unpublished and brought to my attention by Delia Scheffer.

82 See footnote 26.

83 Cited by J. Warren (2014): op. cit. (note 44).

84 catalogo.beniculturali.it/detail/HistoricOrArtisticProperty/0900747095. A gilt bronze example in a later wooden frame. The pax entered their collection in 1866.

85 See footnote 25.

86 Email communication, 2024.

87 Elkan collection, 1934, no. 488, p. 73.

88 See footnote 24.

89 See footnote 26.

90 Cahn auction, 7-8 December 1920, lot 128.

91 Sotheby’s auction, New York, 11 January 1995.

92 See footnote 51.

93 A. Reichmann, Halle, 5 February 1925.

94 Rudolph Lepke’s Kunst-Auctionshaus, 22-23 April, 1913, lots 655-56, p. 47.

95 Formerly in the collection of David Abbate and sold by the present author at Morton & Eden auction, UK, 2016.

96 Galerie Moenius auction, 23 March 2018, lot 83.

97 F. Rossi (2011): op. cit. (note 27). Acquired at Sotheby’s, London, 7 December 1995.

98 Email communication, 2016.

99 See footnote 23.

100 Previously in the Sylvia Adams collection, Bonhams auction, UK, 1996, lot 151.

101 See footnote 28.

Leave a comment