by Michael Riddick

Preview / download PDF in High Resolution

Preview Italian version at Antiqua Nuova Serie

PART 2 of a SERIES OF FIVE PLAQUETTE STUDIES CONCERNING MODERNO AND HIS SCHOOL

Galeazzo Mondella, called Moderno, was the most prolific producer of small bronze reliefs of the Renaissance. While some of his productions were evidently conceived as independent works-of-art others were likely intended to be grouped in a series. Further examples ostensibly sought to preserve creations conceived by him originally in more precious materials.

Throughout the course of scholarship various bronze plaquettes attributed to Moderno have instead been reallocated to followers or presumed anonymous workshop assistants. These artists are today identified by pseudonyms like the Master of the Herculean Labors, the Coriolanus Master, Master of the Orpheus and Arion Roundels, Master of the Corn-Ear Clouds, the Lucretia Master, et al.

While many of these pseudonyms have been applied only in the last few decades, the proposed identity of these artists or their possible reassessment back to Moderno has been little explored due to an absence of information or further critique. However, certain observations may yield reasonable suggestions concerning their context or authorship, particularly as regards the work of Matteo del Nassaro, a gem-engraver whom Giorgio Vasari noted had been a pupil of Moderno as well as a pupil of Moderno’s Veronese contemporary Niccoló Avanzi.

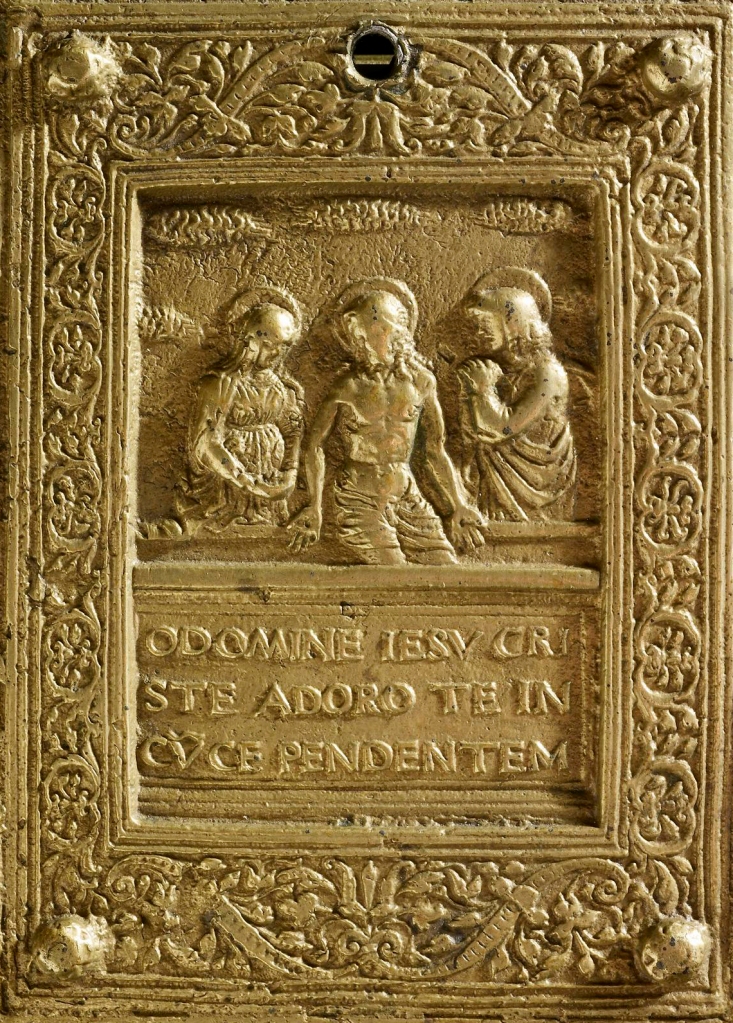

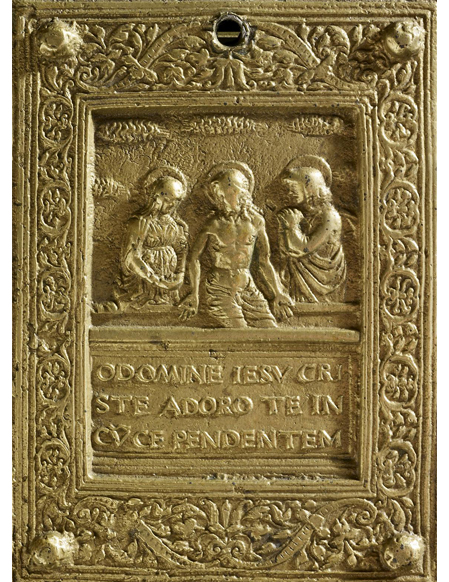

The unusual epithet of the Corn-Ear Master—assigned by Giuseppe and Fiorenza-Vannel Toderi—is given on account of the distinctive manner in which clouds are rendered in the shape of ears-of-corn on this artist’s plaquette reliefs.1 Four works are associated with this maker: a Deposition from the Cross and Entombment (fig. 01); and a Virgin and Child (fig. 03) and Imago Pietatis (cover, fig. 04).

Fig. 01 – Bronze plaquette of the Deposition from the Cross by the Corn-Ear Master, after Andrea Mantegna, late 15th century, Mantua (?) (left; National Gallery of Art, DC, inv. 1957.14.368); Bronze plaquette of the Entombment by the Corn-Ear Master, after Andrea Mantegna, late 15th century, Mantua (?) (right; Museo Nazionale del Bargello)

The Corn-Ear Master is presumed to have been active in either Mantua, Ferrara, Venice or Padua, the former chiefly believed on account of the artist’s reference to Andrea Mantegna’s compositions. For example, the Deposition from the Cross and Entombment plaquettes both copy Mantegna’s prints of these same subjects (fig. 02) and appear to have been made as a pendant set,2 while the figure of St. John at the right of Mantegna’s Entombment is again reprised on the Corn-Ear Master’s Imago Pietatis relief.

Fig. 02 – Engraved print of the Deposition from the Cross, attributed to Andrea Mantegna, ca. 1465 (left; Art Gallery of New South Wales, inv. 8512); Engraved print of the Entombment, attributed to Andrea Mantegna, ca. 1470-75 (right; National Gallery of Art, DC., inv. 1986.98.1)

The artist’s ambit to Moderno has been suggested most notably in regard to the Virgin and Child plaquette which appears to show his influence (fig. 03).3 This is particularly evident in the treatment of the Virgin’s face, hair and clothing. The Imago Pietatis is much more naïve in realization but also bears a particular semblance to a plaquette of the Dead Christ Supported by the Virgin and Saint John considered close to Moderno or made in his workshop.4 It’s border stylistically imitates the bordered format of the Virgin and Child plaquette. The Mantegna influence superficially connects this artist also to Moderno as Moderno’s earliest plaquettes likewise exemplified Mantegna’s distinct influence.

Fig. 03 – Bronze plaquette of the Virgin and Child by the Corn-Ear Master, possibly 1490’s, Milan or Venice (?) (Palazzo Madama, inv. 1113)

In addition to Moderno’s early presence in Mantua throughout the 1490’s, it is quite reasonable to suggest the Corn-Ear Master may also have been active in Mantua on account of his reproduction of Mantenga’s compositions. Mantenga was particularly austere about the reproduction of his designs, at least in the form of engravings. This is evinced in his contract with the goldsmith Gian Marco Cavalli who was commissioned to engrave copperplates after his designs. All drawings and copperplates were to be kept private and could not be reproduced without permission, subject to fiscal penalties. He is noted to have also later hired a band of thugs to assault the engravers Simone Ardizoni of Emilia and Andrea Zoan for potentially copying his designs without permission.5 Andrea appears to have been a pupil of Mantegna’s, presumably entrusted at one point with his drawings and the copperplates after his designs. On account of this we might presume either Mantegna’s patrons, the Gonzaga family or someone close to the Gonzaga or Mantegna himself could only have authorized the small-scale reconfiguration of Mantegna’s designs in these small reliefs by the Corn-Ear Master that were presumably made during the late 15th century while Mantegna was still living.

Fig. 04 – Detail of a bronze plaquette of the Imago Pietatis by the Corn-Ear Master, possibly 1490’s, Milan or Venice (?) (British Museum, inv. 1915,1216.174)

Another possible clue concerning the Corn-Ear Master’s activity could be inferred by the Imago Pietatis relief, which is evidently a pendant to the Virgin and Child relief but features an alternative border treatment with tightly packed palmettes (fig. 04). The borders are executed with an elegance seemingly disparate from the central scenes and could have possibly been conceived by a different artist or a collaborator.

Presumably undiscussed is the inscription featured on the Imago Pietatis relief which reads:

O DOMINE IESV CRISTE ADORO TE IN CVCE PENDENTEM

or alternatively,

O DOMINE IESV CRISE ADORO E IN SEPVLCR

The first inscription refers to the beginning of seven medieval prayers attributed to St. Gregory, which, during the 1400’s, became associated with the iconography of the Imago Pietatis.6 The latter inscription refers to the fourth prayer in the sequence. In particular they point to the late 14th century meditation on the Passion of Christ found in printed and manuscript versions of the Horae (Books of Hours), which were produced in printed and manuscript form throughout the 15th century and thereafter. The devotional prayers of St. Gregory were occasionally added to these Horae along with Marian devotions, dependent on a patron’s taste.

These two subjects of the Imago Pietatis and devotions to the Virgin Mary appropriately relate to the Corn-Ear Master’s pendant plaquettes and to Jeremy Warren’s observation that these two reliefs may have been employed as bookplates for bindings,7 presumably a Book of Hours or devotional work.

It could be further surmised that the book for which these reliefs were conceived was probably an illuminated copy of reasonable expense to match the quality and cost of commissioning such fine book plates to adorn it.

It is perhaps unlikely that the bronze plaquettes themselves were used as covers, as they reproduce the integral bosses along their corners which would have originally been individual objects used to help secure the separately prepared plate to the binding itself. They appear to instead reproduce or preserve the impression of what must have been a celebrated original, possibly a work realized in gilt silver.

Of further note is the choice feature of the ‘O Domine Jesu Christe’ prayer on the Imago Pietatis plaquette. This prayer was especially popularized in the Milan during the last quarter of the 15th century where the series of private devotional invocations of St. Gregory were set to music, called motets.8 In addition to private devotion, they were also used to embellish votive services held in the court chapel9 or performed during the mealtimes of nobility.10

Its appreciation may have been connected to early circulated copies of the Decor Puellarum11 printed by Nicolas Jenson in Venice in 1471 although its developed popularity is attested in Josquin des Prez’s publication Misse Josquin, printed by Ottaviano Petrucci in 1502. Josquin’s Misse was developed for a female audience and featured various sermons, prayers and hymns and notably included also the motet cycle specifically articulated in nearly the exact same orthographic form as reproduced on the plaquettes:

O Domine iesu christe, adoro te in cruce pendentem… and O Domine iesu christe, adoro te in sepulchro…

The text of Prez’s Misse continues thereafter with several Marian devotions and reiterates again a context for these two plaquettes and their relevance to books.12

Although Josquin’s texts are perhaps too late to be associated with these plaquettes and the size of these printed works is certainly incompatible with the scale of the plaquettes, we can surmise that Prez’s choice use of this orthographic format may be due to his exposure to manuscripts he accessed while employed in Milan at the Sforza court.13

This could suggest the Corn-Ear Master was also active in Milan where he could have been exposed to the developing popularity of this devotional motet and its use by Prez and the Sforza court during the last decade of the 15th century.

Fig. 05 – Girdle Binding for an illuminated Brevarium, late 1450’s (NY Public Library, MS 39)

The subject of these plaquettes and their theoretic use on a book binding consisting of devotional music and prayers, suggests a wealthy female patron commissioned them. This further coincides with Warren’s observation of their scale, which appear to relate to the size of girdle prayer books,14 being a small and luxurious devotional ‘vade mecum’ worn by women which attached to a girdle around their waist.15 The present author furthers this idea, particularly in regard to the unusually scaled bosses which would have helped reinforce the extended leather binding accoutrements used to form a knotted sling from which these books could be fixed to a girdle belt (fig. 05). They could alternatively be supported by fine chains, as observed in a later 16th century portrait of Lady Phillippa Speke (fig. 06). This not only provided convenience for daily reading but also security and a fashionable social statement.

Fig. 06 – Anonymous portrait of Lady Philippa Speke née Rosewell, 1592, oil on panel (private collection)

A natural consideration for such a commission could include Beatrice d’Este, of the Sforza nobility whom, like her sister, Isabella, in Mantua, were both concerned with fashion, luxury, patronage, social status and each shared a passion for singing and playing instruments.16

In particular, we know Isabella took great care in the few documented books we know she commissioned, emphasizing in particular their quality and representation through fine bindings. In one instance she expressed her choice to have an unidentified master in Mantua bind a copy of Petrarch rather than a Venetian or Flemish binder that had been recommended to her.17

Her important library is testament to her interest in books and her library had an atypically large quantity of manuscripts although the quantity of devotional texts in her collection were comparatively small.18 Nonetheless, her exquisite taste, patronage to a variety of artists and her own talents as a singer and multi-instrumentalist could encourage this idea, if not her sister Beatrice, or a friend like Antonia del Balzo who is known, on a daily basis, to have used a favored illuminated Horae inherited from her father’s library.19 The importance of such a book and their elaborate cover treatments incidentally resulted in the desire to preserve and thus appreciate them through the bronze casts we find with us today in various private and museum collections.

It also remains possible that the Imago Pietatis and Virgin and Child reliefs, although clearly related, could have formed two individually commissioned book covers and might explain why the border treatments vary slightly between them as well as their quality of execution, suggesting some artistic development on behalf of the Corn-Ear Master. We could invite here the idea that the Virgin and Child is the most mature of his four known works and was possibly realized after having hypothetically met Moderno or having been exposed to the master’s work.

From all of these observations we might assume the Corn-Ear Master could have been active, perhaps initially in Mantua, and then subsequently in Milan. We might also entertain the possible idea that the Corn-Ear Master might have traveled or worked in close proximity with a figure like Andrea Zoan, also called Giovanni Antonio da Brescia, who is also thought to have initially been active in Mantua working under Mantenga, and in later years apparently not averse to copying his designs, and was subsequently active in Milan from the 1490s.20 The Corn-Ear Master’s known works being derived from prints after Mantenga and his production of two bookplates for a binding, possibly made in Milan, might logically connect him to Andrea’s orbit. If the Corn-Ear Master worked with or knew Andrea we could also interject Andrea’s association with the Sforza court miniaturist Giovanni Pietro da Birago, whose fine productions required exceptional bindings. The winged putti and child Christ on the Virgin and Child plaquette particularly recall the typology of Giovanni Pietro’s inventions, inclusive also perhaps of the ornate miniaturist-inspired borders found on this and the Imago Pietatis plaquette. There is also a slight Leonardesque influence in the Virgin and Child configuration, reminiscent of his pupil’s works like those of Marco d’Oggiono or Giovanni Pietro Rizzoli, called Giampietrino. The possible touch of Moderno’s influence on this plaquette, if realized in Milan, could again bring credence to Paola Venturelli’s suggestions for Moderno’s possible activity in Milan during occasional points of his career.21

While these proposed regions of activity for the Corn-Ear Master remain speculative, although considerable, the recent suggestion of a Venetian origin by Warren22 and the long-held notion of an origin in Padua cannot be ruled out nor Francesco Rossi’s educated guess of a possible origin with the Paduan bell founder, Pietro Di Gaspare called Pietro Delle Campane, which remains interesting.23

Endnotes:

1 Giuseppe and Fiorenza-Vannel Toderi (1996): Placchette Secoli XV-XVIII nel Museo Nazionale del Bargello. Firenze, no. 250, p. 138.

2 See for example a pair of these two plaquettes fused together in a single cast at the Palazzo Madama, Inv. 1154.

3 Ernst Bange first suggested this artist’s ambit to Moderno while John Pope-Hennessey considered the possibility of Moderno’s own hand in their execution. See Ernst Bange (1922): Die Italienischen Bronzen der Renaissance und des Barock, Zweiter Teil: Reliefs und Plaketten. Berlin and Leipzig, no. 518, p.71, and John Pope-Hennessy (1965): Renaissance Bronzes from the Samuel H. Kress Collection. Reliefs, Plaquettes, Statuettes, utensils and mortars. London, no. 316, p. 90.

4 Douglas Lewis (1989): The Plaquettes of ‘Moderno’ and His Followers in Studies in The History of Art, vol. 22, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC., pp. 105-41. See National Gallery of Art, Inv. 1957.14.369.

5 Keith Christiansen (2009): The Genius of Andrea Mantegna. Metropolitan Museum of Art and Yale University Press, see pp. 48-51.

6 Kathryn Rudy (2017): The Mass of St Gregory, the Man of Sorrows, and Prayers for the Arma Christi in Rubrics, Images and Indulgences in late Medieval Netherlandish Manuscripts. Brill, pp. 101-36.

7 Jeremy Warren (2014): Medieval and Renaissance Sculpture in the Ashmolean Museum, Vol. 3: Plaquettes. Ashmolean Museum Publications, UK, no. 380, pp. 918-19.

8 Warren Drake (1997): A New Source for the Text of Josquin’s Passion Motet Cycle O Domine Jesu Christe in Journal of Music Research, no. 13, pp. 35-46.

9 Howard Mayer Brown (2018): Mirror of Man’s Salvation in Renaissance Quarterly, no. 43, Cambridge University Press, pp. 756-57.

10 Anthony Cummings (1981): Towards an interpretation of the sixteenth-century motet in Journal of the American Musicological Society, no. 34, pp. 43-59.

11 Francesco Trevisan (attr.) (1471): Questa sia una opera la quale si chiama decor puellarum zoe honore de le donzelle : la quale da regola forma e modo al stato de le honeste donzelle : [D]ilectissime fiole in Christo Iesu, published by Nicolas Jenson, Venice.

12 Prez’s popular ‘O Domine Jesu Christe’ is subsequently featured in Petrucci’s 1503 compilation of motets from a variety of composers in his Motetti de passione de cruce de sacramento de beata virgine et huiusmodi B, attesting to its popularity at this time.

13 Consider, for example, Julie Cumming’s analysis of the manuscript sources for Ottaviano Petrucci’s 1503 publication, Motetti de passione de cruce de sacramento de beata virgine et huiusmodi B, in which Josquin Prez’s motet, ‘O Domine Jesu Christe,’ is printed. See Julie Cumming (2010): Petrucci’s Publics for the First Motet Prints in Making Publics in Early Modern Europe: People, Things, Forms of Knowledge. Routlledge, pp. 96-122. For Josquin’s employ under the Sforza see Lora Matthews and Paul Merkley (1994): Josquin Desprez and his Milanese Patrons in The Journal of Musicology, vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 434-63.

14 J. Warren (2014): op. cit. (note 7).

15 Hugh Tait (1985): The Girdle-Prayerbook or Tablet: An Important Class of Renaissance Jewelry at the Court of Henry VIII in Jewellery Studies, 2, pp. 29-57.

16 Sara Jacomien van Dijk (2015): Beauty Adorns Virtue – Dress in portraits of women by Leonardo da Vinci. PhD thesis, Universiteit Leiden. See chapter 4, pp. 109-37.

17 Giuseppe Campori (1872): Notizie dei miniatori dei principi estensi, Modena and Vincenzi, pp. 18-19.

18 Brian Richardson (2012): Isabella d’Este and the Social Uses of Books in La Bibliofilia, vol. 114, no. 3, pp. 293-326.

19 D.S. Chambers (2007): A Condottiere and his Books: Gianfrancesco Gonzaga (1446-96) in Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, vol. 70, pp. 33-97 (see p. 83).

20 Devon Maker (2016): Printing Beyond Boundaries: The Use of Northern Prints in Renaissance Milan in Athanor XXXIV, pp. 25-31.

21 Paola Venturelli (1999): Leonardo e i leonardeschi : temi di arte applicate. Marsilio, Venice.

22 See J. Warren (2014): op. cit. (note 7). Warren comments on the possible Venetian manner of the borders featured on the Corn-Ear Master’s Virgin and Child and Imago Pietatis reliefs, and we may further consider a Venetian origin if we are to assume the feature of the text on the Imago Pietatis plaquettes have nothing to do with their development into motets in Milan but rather simply aim to reproduce the prayer of St. Gregory in the 1471 edition of the Décor Puellarum published in Venice and presumably being used for an Horae bound in that city.

23 Francesco Rossi (2011): La Collezione Mario Scaglia – Placchette, Vols. I-III. Lubrina Editore, Bergamo, nos. III.3-5.

Leave a comment