by Michael Riddick

Preview / download PDF in High Resolution

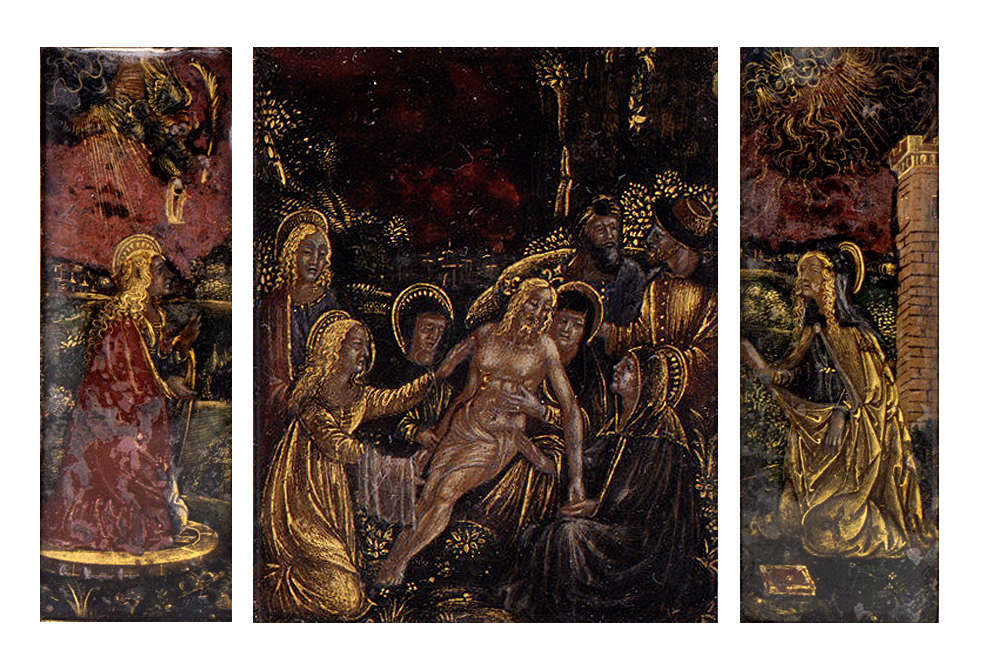

Presented here are new observations regarding a pax featuring two reverse painted rock crystals of Lombard origin, probably Milanese, ca. 1500-10 for the central scene and ca. 1575-1600 for the base applique (Fig. 01).[1]

Reverse painted and gilt compositions on rock crystal comprise a highly technical virtuosity in which gold gilding was first applied to the interior of a polished crystal surface followed by painted tones in tempera or oil and sequentially rendered in a reverse process that first applied lighter colors followed by dark colors. Great vision and skill were required of the artists responsible for these fine miniatures whose tradecraft was centralized in Milan, a derivative of the talented illuminators who gathered under the court of the Sforza family during the end of the 15th century.

The central scene of the pax depicts a beautifully accomplished Lamentation (Fig. 02) which Silvana Pettenati describes as Leonardo-esque in its inspirations,[2] an artist whose activity in Milan had an indelible impact. Pettenati further compares the painting to the illuminated miniatures of Cristoforo de Predis (1440-86). However, the present author suggests stronger comparisons with other illuminators. Though active in Ferrara, the artist of the Lamentation evokes the mood of Cosimo Tura’s (1430-95) paintings and illuminations with a sensibility toward his serene facial expressions and anatomical manner. However, a greater influence is indebted to the miniatures of Milan’s Giovanni Pietro di Birago, active from 1471-1513. The facial features, tightly coiled hair, thick classical draperies and foliage observed in the Lamentation painting relate to Giovanni Pietro’s illuminations (Fig. 03).

While reverse painted miniatures are challenging to distinguish on account of their patently similar influences and small size, a detailed analysis of brushwork, scale and stylistic tendencies may allow for the grouping of some works to certain unidentified artists.[3] A painting at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) (Fig. 04),[4] probably intended for a pax, is conceivably by the same hand, or belonging to the same circle as the artist responsible for the Lamentation painting. In particular, the remarkable finesse given to the gold coiled hair, the plasticity of the painted faces, the corresponding foliage and the rendering of heavy, classicized draperies conform and share the same previously noted influences from Giovanni Pietro’s miniatures. The depiction of the saint on the right of the LACMA Sacred Conversation painting relates to Giovanni Pietro’s representation of St. John on the opening page of the Gospel of John in the Sforza Hours, ca. 1490 (Fig. 05).[5] The linear handling of the brushwork employed on the draperies and flesh tones of the Lamentation and Sacred Conversation paintings closely compare with Giovanni Pietro’s technique (Fig. 06) and could suggest their author was someone close to his circle, a member of his workshop or at least an artist experienced in the skill of illumination.

Pettenati describes the pax frame as Lombard in origin and compares it with three paxes at the Louvre[6] that are representative of Milan’s exceptional talents during the turn-of-the-century, incorporating reverse glass painting, enamel, niello and goldsmiths-work. However, a closer comparison of the Louvre group and the present pax indicate a gap in quality which was earlier observed by Vittorio Viale who called it “sloppy and unkempt.”[7] In Viale’s description of the object he leaned toward a generic North Italian origin for the frame and a dating to the second half of the 16th century, seeking to distance it from the finer accomplishments in early 16th century Lombardy. Viale and Pettenati were in unison with their agreement that the frame was made during the second half of the 16th century and that the reverse painted crystal Crucifixion mounted on the base was likewise a later addition and executed by a different, yet gifted artist.

It is not noted by Pettenati but it appears the central painting may not have a rounded top and could be square, its upper corners possibly hidden behind the arched frame.[8] Such an unusual characteristic would inform us that the frame was not uniquely prepared for the painting but was instead salvaged as an adequate way to display the painting at a later date. Further suggestive of its potentially square shape is the presence of a weaker copy of the Lamentation at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (MET) that is square (Fig. 07).[9] The Turin Lamentation has stronger definition and a more precise management of the brush. The gradated tones are smooth and painterly while the tonal changes depicted in the MET example are less proficient. Likewise, the convincing emotional power of the Turin Lamentation is compelling while the MET example is a dulled vestige.

The MET tabernacle’s flanking panels depicting the Annunciation on the left and Mary Magdalene on the right suggest the original Turin Lamentation may have once had accompanying paintings, now lost. As a result of such a loss, the Turin Lamentation may have found a new home in the present unrelated pax, divorcing it from its original context.

Contrarily, the Turin Lamentation may indeed have an arched top as the upper corners of the square MET example do not add any significance to the composition and the related LACMA painting appears to have originally been conceived with an arched top. Generally, however, reverse crystal paintings in this format are less common.

Of greater interest with regard to the MET’s Lamentation is the apparent faithfulness of its maker in copying the Turin example. The MET Lamentation copies the Turin painting in every detail with the only noteworthy error being the right hand of Mary placed awkwardly in front of Christ’s hip, unlike the Turin example which supports him tenderly. Such practice of direct copying is rare for the medium and while many examples of the same subject are reproduced on quantities of reverse painted crystals, they tend to differ in essential details and stylistic treatments while following common models only loosely. However, in the case of the MET Lamentation there is a very deliberate attempt on the part of the artist to reproduce a finer example and this might lead us to assume we have an apprentice seeking to copy his teacher’s work. The two paintings might offer a glimpse into the workshop practices involved in the production of these rarefied paintings, produced chiefly for only a brief window of time during the mid-to-late Renaissance.

Although a Lombard and North Italian origin for the pax frame have been offered by Pettenati and Viale, the frame is actually Spanish. Spain is also probably the location where the object was assembled in its current form and possibly as late as the early 19th century.[10] Letizia Arbeteta Mira has discussed the serial export of reverse painted crystals to Spain from Milan.[11] Many examples are found in Spanish mounts which has formerly led scholars to mistake Milanese artworks for Spanish ones. The tradecraft did eventually carry over into Spain but at a later date than the period assigned to the Turin Lamentation.[12] A natural genesis of the art was established in Milan due to the school of illuminators present there as well as the accessibility of rock crystal,[13] as Milan was the zenith of artistic rock crystal production in 16th century Europe.[14] While most examples of reverse painted rock crystals in Spain are known as individually mounted pendants these objects were also set into larger works of fine metal. One example is the Sorlada reliquary casket in Navarra which features fourteen examples mounted to its exterior.[15]

In addition to adding the Lamentation painting, the assembler of the Turin pax has also affixed the reverse painted Crucifixion pendant to its base, replacing what was probably a lost gilt metal cartouche applique bearing a cross or coat-of-arms, as was typically applied to Spanish paxes (Fig. 08).

The frame probably dates to the final years of the 16th century or the first years of the 17th century. Its architectural form recalls the type of paxes made during the mid-16th century by Francisco Becerril (Fig. 09). The arched interior window flanked at the top by winged putto heads and surrounded by a wide and undecorated margin with room to display a pair of columns is typical of the paxes made by Becerril and his followers. The Turin pax may have once displayed a small relief in metal, now replaced by the Lamentation painting. The entrecoupé of the Turin pax further recalls the influence of another Spanish pax maker, Hernando de Ballestros, active around 1575, whose designs make use of similar entrecoupés topped by a triangular pediment (Fig. 10). It is doubtful either of these sculptors are reasonable for the Turin pax frame as it appears to be a later synthesis of their styles.

The sirens that flank the top of the Turin pax resemble motifs also found on Spanish paxes such as one example from the Madeira Museum of Sacred Art (Fig. 11). The silhouetted winged putto head featured in the entrecoupé is also typical of stylized designs of winged putto by Spanish goldsmiths active toward the end of the 16th century (Fig. 12). Judging by the date of the pax frame, an entire century or more may have passed before the Lamentation painting found its current home in its Spanish frame, its possible original flanking painted panels broken or lost to the ravages of time.

Special thanks to Letizia Arbeteta Mira for her kind input on the subject of reverse painted rock crystals.

ENDNOTES

1. The pax was given to the city of Turin by the art dealer Pietro Accorsi in 1935, once forming part of the Trivulzio collection. The pax currently resides at the Palazzo Madama: Inv. 0082 / VD (formerly Inv. V.O. 236)

2. Silvana Pettenati: I vetri dorati graffiti e i vetri dipinti, Museo Civico di Torino, 1978; p. 29

3. To the present author’s knowledge no stylistic analysis of unsigned or undocumented works by the artists responsible for these micro-paintings has been undertaken.

4. Los Angeles County Museum of Art: Inv. M.87.140; judged ca. 1480 though the present author suggests ca. 1490-1510

5. British Library: Sforza Hours, Add.MS 34294, folio 1r

6. Louvre: Inv. Nos. OA10584, OA5562 and OA5582

7. Vittorio Viale: Bollettino della Società Piemontese d’Archeologia e di Belle Arti. I principali incrementi del Museo Civico di Arte Antica, 1948; pp. 45, 47

8. An in-person inspection of the pax would quickly solve this question but the present author relies only on photographs and is not presently in communication with anyone at the Palazzo Madama to confirm or deny this observation.

9. Metropolitan Museum of Art: Inv. 17.190.1404

10. Alternatively, a Spanish frame could have ended up in Italy, found by a resourceful Italian collector or metalworker and assembled.

11. Letizia Arbeteta Mira: Obras maestras de la Colección Lázaro Galdiano (Catálogo de Exposición, 16 de Diciembre de 2002 – 9 de Febrero de 2003), Fundación Santander Central Hispano, Madrid, 2002

12. Letizia Arbeteta Mira comments on the phases for the developmental evolution of this art type in the territories of Italy, Spain and Mexico (“New Spain”). (private communication, Dec. 2016)

13. Raw crystal was mined from the nearby St. Gotthard Pass.

14. Letizia Arbeteta Mira: Arte transparente: la talla del cristal en el Renacimiento milanés, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid, 2015

15. Ignacio Migueliz Valcarlos: Medallones relicarios de escuela lombarda en una pieza de orfebrería navarra: el arca relicario de Sorlada. OADI: Rivista dell’Osservatorio per le Arti Decorative in Italia (DOI: 10.7431/RIV06052012), 2012

Leave a comment