by Michael Riddick

Preview / download PDF in High Resolution

Italian ceroplastics, a discipline rooted in the ancient lost-wax bronze casting tradition, reached its zenith during the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries as an autonomous and profound medium for exploring the duality of human existence. This art form was profoundly shaped by Gaetano Giulio Zumbo (1656–1701), the Syracuse-born master whose tenure in the Medici court of Florence defined a new standard of polychrome wax virtuosity.1 Zumbo’s work, particularly his famed theatrical plague scenes and anatomical groups like The Corruption of Bodies (fig. 1), transformed wax from a mere commercial model into a sophisticated vehicle for Baroque meditations on the passage of time and the inevitable dissolution of the body.2

Fig. 1: Wax teatrini depicting The Corruption of Bodies, by Gaetano Giulio Zumbo, 1694 (Natural History Museum, La Specola, Florence)

As the predecessor and chief influencer of the anonymous artist dubbed the ‘Scandalosa Master,’ Zumbo’s legacy was carried forward by a generation of artists who maintained a unique and intimate tie to religious and charitable orders. Notably, Caterina de Julianis (c. 1670–1742), often identified as a pupil or close follower of Zumbo, joined the Clarisse nunnery in Naples, where she continued to produce highly detailed memento mori waxworks that fused scientific curiosity with monastic devotion.3 This professional and spiritual landscape—where the ceroplast functioned simultaneously as a scientific documentarian and a moralizing theologian—created the specific institutional environment from which the Scandalosa Master emerged. Presumably operating within the specialized rituals of Neapolitan confraternities like the Bianchi della Giustizia, the Master took Zumbo’s foundation of anatomical realism and redirected it toward a localized, visceral verismo born of the hospital ward and the scaffold.

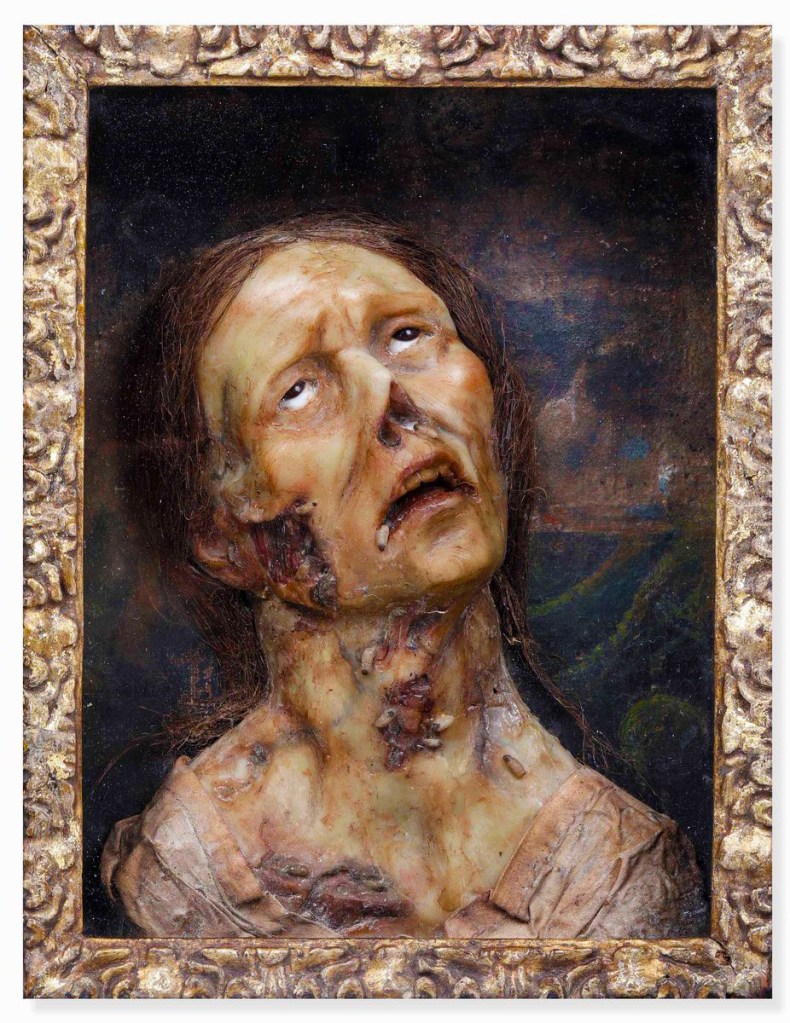

The emergence of the Scandalosa Master in early eighteenth-century Naples represents one of the most provocative intersections of clinical observation and Counter-Reformation theology in the history of Western art.4 To understand this anonymous master, one must first surrender the notion of the artist as a solitary romantic figure and instead view him as a specialized institutional operative—a technician of the sacred and the profane who functioned within the social and spiritual machinery of the Ospedale degli Incurabili in Naples. Building upon the foundational research initiated by Regina Deckers, who first contextualized the wax tableau dubbed La Donna Scandalosa (fig. 2),5 this paper seeks to expand the master’s catalog by analyzing additional distinct works—ranging from public moralizing teatrini to private anatomical specimens. This master was likely a plasticatore or moulage specialist attached to the Congrega dei Bianchi della Giustizia,6 the elite confraternity tasked with the confortoria, the final spiritual care of those condemned to death.7 This professional proximity to the scaffold and the hospital ward provided the master with a certain “Anatomical Privity”—a firsthand witness to the body’s trauma—that separates his work from the more allegorical, refined waxworks of Zumbo. Where Zumbo sought to capture subjects like the Triumph of Time through a classical lens, the Scandalosa Master sought to document the “Scandal of the Flesh” through a pathological one.8 His oeuvre, which we can now begin to assemble through a series of primary works, reveals a hand that was intimately familiar with the chemical formulas of decay, the biological reality of infestation, and the specific contextual topography of Neapolitan suffering.

Fig. 2: La Donna Scandalosa by the Scandalosa Master, probably ca. 1720s, wax, linen, hair, stucco and linen (Oratorio dei Bianchi at the Ospedale degli Incurabili, Naples)

The context of the Bianchi della Giustizia is essential to painting the picture of the master’s environment.9 The confraternity operated in a state of constant religious fervor, driven by a mission that required them to witness the most extreme transitions of the human condition. As they accompanied the condemned during their final three days, the Bianchi were not simply observers; they were intercessors between the carnal reality of the prisoner and the eternal judgment of the soul.10 The Scandalosa Master’s work is the visual manifestation of this intercession. Deckers posits these sculptures were not only art; they were “ethical challenges,” designed to shock the viewer—specifically ‘fallen’ women and prostitutes who were often the primary target of these moralizing spectacles—into a state of immediate repentance.11 This required a level of realism that surpassed traditional sculpture. It required a verismo so total that the viewer could not retreat into the comfort of artifice. To achieve this, the master developed a distinct technical signature characterized by the use of spirit-based varnishes to simulate wet liquefactive necrosis, creating a sickly, glistening surface on exposed muscle and bone that mimics the actual moisture of a fresh cadaver. This “wet” look, which stands in stark contrast to the dryer, more matte finishes of the Florentine school, is a primary technical fingerprint of the master’s late-period workmanship.

One of the more notable technical features of the Scandalosa Master’s work was his integration of real materials into the structural and surface integrity of the wax. This is perhaps most evident in his use of the wax-linen shroud, modeled while hot. Rather than sculpting drapery from pure wax, which would be fragile and prone to sagging, the master utilized real linen soaked in a mixture of wax and possibly high-melting-point stucco. This fossilized textile served as a rigid shell or armature, providing the necessary support for the heavy wax bust while acting as a bridge between the physical world of the viewer and the rotting world of the specimen.

Furthermore, the Master’s pursuit of hyper-realism extended to the use of real human hair, which was meticulously punched or rooted into the softened wax scalp to simulate thinning patches and pathological alopecia. While these may not be his own isolated technical innovations, as the use of mixed media was a burgeoning practice in 18th-century Neapolitan ceroplastics, the Master employed them with a unique clinical precision. These real-world materials transformed the sculpture from a mere artistic representation into a “clinical specimen,” collapsing the distance between the artifice of the waxwork and the biological reality of the body.

In the seminal work from which the artist’s epithet is derived—the Donna Scandalosa (fig. 2), located in the Oratorio dei Bianchi at the Ospedale degli Incurabili—this rigid drapery serves as a macabre frame for a bust that remains a masterclass in clinical, pathological documentation. The Master modeled teeth set into receding, pigmented wax gums to simulate the effects of osteomyelitis and bone erosion common in advanced tertiary syphilis (Lues venerea) while the mouth is caught in a paroxysm, a silent scream of agony that serves as a visceral reminder of the physical consequences of a dissolute life. This facial tension, where the jaw is locked in a terminal gasp, is a hallmark of the master’s work, appearing consistently across his expanded oeuvre.

The biological accuracy of the Scandalosa Master extends beyond human anatomy to the entomological life cycles that follow death. Influenced by the scientific breakthroughs of Francesco Redi, who disproved spontaneous generation by studying the generation of insects in rotting meat, the Master treated maggots not as generic symbols of death, but as biological inhabitants of the corpse.12 In the Master’s work, the larvae are not simply stuck onto the surface; they are embedded within the wax, appearing to emerge from the necrotic layers of the cheeks, neck, and orbital sockets. They follow the wet pathways where fly-strike would naturally occur in a biological setting. In the more public, allegorical teatrini, this ecosystem is expanded to include a specific theological script: the lizard on the left, a symbol of the soul’s endurance or the fires of purgatory, and the rat on the right, the scavenger that consumes the final remnants of earthly vanity. These animals are often depicted with the same hyper-realism as the human subject, their scales and fur rendered with a fidelity that suggests the Master was working from true-to-life observation.

The stylistic trajectory of the Scandalosa Master reveals a profound evolution in both technical execution and pathological observation, moving from a foundational engagement with Zumbo’s legacy toward a visceral, localized verismo. By analyzing the wax tonalities and material signatures across these works, we can map the Master’s accurate portrayal of advanced syphilis characterized by sallow, leaden skin tones and the systemic erosion of bone and tissue.

Fig. 3: A Vanitas bust, ca. 1700s-10s, Naples, possibly by the Scandalosa Master (?), wax and linen (Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples)

A critical, if tentative, entry point into this phase is the wax bust currently held at the Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte (fig. 3).13 Dated around 1700, this free-standing work introduces the specific clinical markers that define the Master’s later hand, yet the wax appears denser and more monolithic in tone compared to the Donna Scandalosa (fig. 2). Its execution remains less sophisticated, particularly regarding the unrefined application of the linen shroud; notably, the artist has incorporated striated and etched lines into the linen to retrieve the texture lost through the oversaturation of wax on the cloth. While it lacks the complex stained quality of later necrotic works, the tension in the jaw and the rolling of the eyes provide the structural foundation for the Scandalosa Master’s mature psychological style. The modeled worms here are somewhat clumped, suggesting a master who is still perfecting the biological ecosystem of the corpse. The absence of rooted human hair on this molded scalp necessitates a degree of scholarly timidity in its here proposed attribution, marking it as a preliminary creation before the Master adopted the mixed-media standards of Neapolitan ceroplastics.

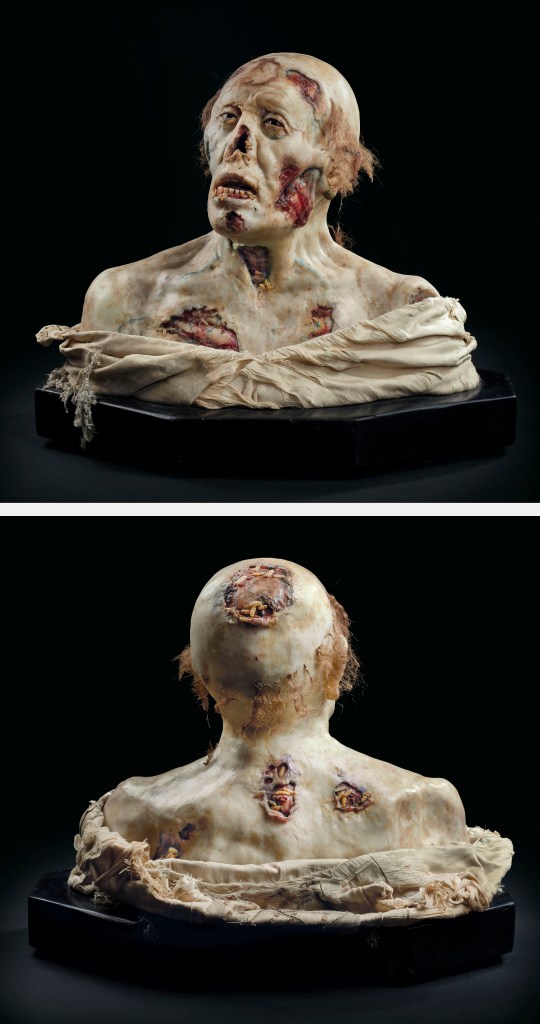

Fig. 4: An Anatomical Bust with Worms, here attributed to the Scandalosa Master, possibly ca. 1715-25 (?), wax, paint, hair, stucco (Longari Fine Art, Milan)

This developmental phase finds a provocative expression in a work formerly with Longari Fine Art, dubbed an Anatomical Bust with Worms (fig. 4).14 While presently attributed to Zumbo, a closer examination invites a challenge to this consensus, as the sculpture features a specific neck wound—characterized by dark compression—suggesting a direct observation of scaffold trauma to which the Scandalosa Master would have been regularly privy. While the sculpture shares Zumbo’s fascination with decay, the execution demonstrates a level of clinical individuality and pathological detail, inclusive of liquefactive necrosis, that aligns more closely with the institutional environment of the Incurabili than with Zumbo’s dryer, Florentine-inspired finishes. This technical deviation suggests that while Zumbo remained a master of the classical allegory of decay, the Scandalosa Master had begun to pioneer a localized pathology of it—one that favored the grit of the autopsy over the grace of the theater.

Furthermore, the work offers a specialized moral indictment that transcends mere anatomy. The presence of a moth on the proper right pectoral is a rare iconographic inclusion in Neapolitan ceroplastics, likely referencing the Gospel warning against storing “treasures on earth” where “moth and rust destroy” (Matthew 6:19). This detail, combined with the subject’s distinctive baldness, invites a provocative re-reading of the figure as a fallen cleric. If the scalp represents a defiled tonsure rather than mere pathological alopecia, the moth serves as a silent witness to the corruption of sacred vows. The lack of a robe also suggests part of the de-frocking ritual while the Master, as an operative of the Bianchi, would have been one of the few to witness the subject in this transition: a man whose ‘sacred’ body had been officially rendered ‘profane’ and subject to the law of the rope. While local archives of the Bianchi della Giustizia are not accessible to the present author, there are mentions of preti assassini (murderous priests) who were executed for crimes of passion or for inheritance disputes during this period.

The Longari bust also marks the advent of the rooted hair technique within this theoretical oeuvre—present at least on the large rat on the shoulder—demonstrating that the Master treated animal and human specimens with the same clinical scrutiny. This single rat, mirrored also in the Sicilian example (fig. 6), to be discussed, establishes a consistent pathological signature for those whose social or religious standing made their dissolution a possible matter of public gravity. Finally, the color palette of the painted backdrop, with its ochre and gray-blue hues, is commensurate with the Master’s other topographical works, while the feature of stones forming part of the theater’s backdrop relates to the “Sermon of the Dilapidated House,” in which we read: “… your flesh is but a stone in the field,” to be discussed.

Fig. 5: A Man with Syphilis, here attributed to the Scandalosa Master, possibly ca. 1720 (?), wax, hair, stucco, and linen (private collection)

Related to this group is an artwork offered by Bertolami Fine Art (fig. 5),15 which serves as a technical “Rosetta Stone.” This bust of a syphilis sufferer retains the formative trait of eyebrows modeled directly in the wax, mirroring the Longari bust, yet it introduces a near-complete head of rooted human hair. While the roach on this example is not propped up, as observed on the Longari and Donna Scandalosa examples, the wax exhibits a sallow quality consistent with the master’s accurate portrayal of syphilis. This hybridity represents a moment of transition where the master began to embrace mixed-media traditions without abandoning earlier modeling habits.

La Donna Scandalosa at the Oratorio dei Bianchi (fig. 2) represents the synthesis of these formative traits, showcasing the perfected fossilized linen shroud as an integrated frame for the bust. Notably, the entomological signature here is highly specific: the roach on this specimen is propped up by carefully modeled legs, causing it to rise slightly above the surface of the wax in a three-dimensional stance—a mechanical habit mirrored in the Longari bust (fig. 4). While the sculpture possesses no human hair in its current state, contemporary records describe the work as once featuring “copious locks of black hair.”16 This original mixed-media element would have served as the ultimate marker of Vanitas, heightening the contrast between the subject’s former beauty and her current biological ruin.

Beyond its technical virtuosity, the work suggests a profound awareness of the Redemptorist missionary rhetoric that saturated Naples, specifically St. Alphonsus Liguori’s Apparecchio alla Morte (Preparation for Death). Although codified in the mid-18th century, Liguori’s text was a distillation of earlier Neapolitan missions that famously described the “corpse in the tomb” in terms that mirror the Master’s waxes: “See how that body becomes first yellow, then black… the worms first consume the flesh, then the eyes, then the heart.”17 In this light, the Master’s work appears to be a direct three-dimensional translation of Liguori’s “Holy Terror,” designed to make the abstract warnings of the pulpit unavoidable through the visceral reality of the ceroplastica. While the first official printing of Liguori’s text occurred in 1758, his conversion experience occurred within the Incurabili in 1723. This creates a potent chronological and spatial intersection; the Scandalosa Master and the Saint were likely walking the same wards simultaneously, one translating the “Holy Terror” into wax while the other refined it into prose. This intersection not only helps theoretically date La Donna Scandalosa to the peak of this missionary fervor during the 1720s–30s but suggests that the Master may have personally moved within Liguori’s immediate spiritual circle.

Fig. 6: A Syphilitic Woman flanked by a Lizard and Rat, here attributed to the Scandalosa Master, possibly ca. 1720s-30s, wax, paint, hair, stucco, and linen (private collection)

Transitioning toward the Master’s topographical interests, a privately owned Sicilian example (fig. 6)18 features a ghostly rendering of the facade of the Ospedale degli Incurabili in its background (fig. 7). This architectural elevation pins the death of the subject to the physical reality of the hospital’s wards. The palette of this work—characterized by muddy skin transitions and earthy ochre tones—matches the Donna Scandalosa and the Longari bust with such fidelity that it reinforces the theory of a shared workshop origin and a maturing scenographic vision realized by the artist.

Fig. 7: Detail of the facade of the Ospedale degli Incurabili and an image enhanced version of figure 6.

A similar topographical anchor is found in a work sold by the Cambi auction house (fig. 8),19 which utilizes a painted architectural backdrop depicting a desolate landscape. While the specific background details are indecipherable, the general color palette of ochre and gray aligns firmly with the Master’s topographical interests. In this work, the figure’s expression has evolved into a state of acute, conscious anguish, most evident in the deeply furrowed brow and the heightened tension of the rolling eyes.

Fig. 8: A Syphilitic Woman against a backdrop, here attributed to the Scandalosa Master, possibly ca. 1720s-30s, wax, paint, hair, stucco, and linen (private collection)

The master’s late period is defined by a shift toward more nuanced, localized presentations of trauma and decay. In an example formerly in a private German collection (fig. 9),20 the pathological focus moves slightly away from the systemic sallow-yellow of earlier works. The Master employs a translucent spirit-varnish over the exposed musculature and the necrotic tissue of the neck, creating a glistening, hydrated effect that simulates a fresh anatomical dissection. Unlike the fossilized white linen of the Donna Scandalosa (presumably representing typical infirmary garbs), the inclusion of red silk suggests a noble death, perhaps illustrating the egalitarian nature of syphilis—a disease that did not spare the aristocracy of Naples. The sculpture emphasizes vascular and soft-tissue trauma; deep, dark hematoma-like staining around the jaw and the neck hints at the physical paroxysms of terminal agony or the “Anatomical Privity” of a medical autopsy. The hair is rooted sparingly with strategic alopecia patches, aligning with the chronic hair loss associated with mercurial treatments of the time.

Fig. 9: A Vanitas bust, here attributed to the Scandalosa Master, possibly ca. 1730s-40s, wax, paint, hair, stucco, linen and silk (private collection)

The zenith of this approach is found in a bust sold at Christie’s in 2018 (fig. 10, cover).21 Here, the wax exhibits a nuanced, almost translucent quality that captures the sub-dermal reality of the subject. The tension of the neck—where the master focuses on the underlying laryngeal structure rather than a generic exterior—reinforces the theory that he was working from direct observation within the clinical or forensic environments of the Incurabili. The hair receives the same detailed treatment as the German example, while the palette remains a masterclass in the representation of Tertiary Syphilis, featuring hallmark muddy skin tones punctuated by deep, purplish-black necrotic pits in the neck and jawline. Unlike earlier works where neck trauma is framed by linen, the Christie’s example utilizes the moulage technique to expose the underlying cervical vertebrae. This ‘wet’ spirit-varnish applied to bone and ligaments suggests a fresh dissection, while the dental recession is at its most extreme, with individual teeth appearing loosely seated in eroding gums—a direct clinical observation of the bone-deep effects of Lues venerea.

Fig. 10: A Clinical Vanitas bust, here attributed to the Scandalosa Master, possibly ca. 1730s-40s, wax, paint, hair, stucco, and linen (private collection)

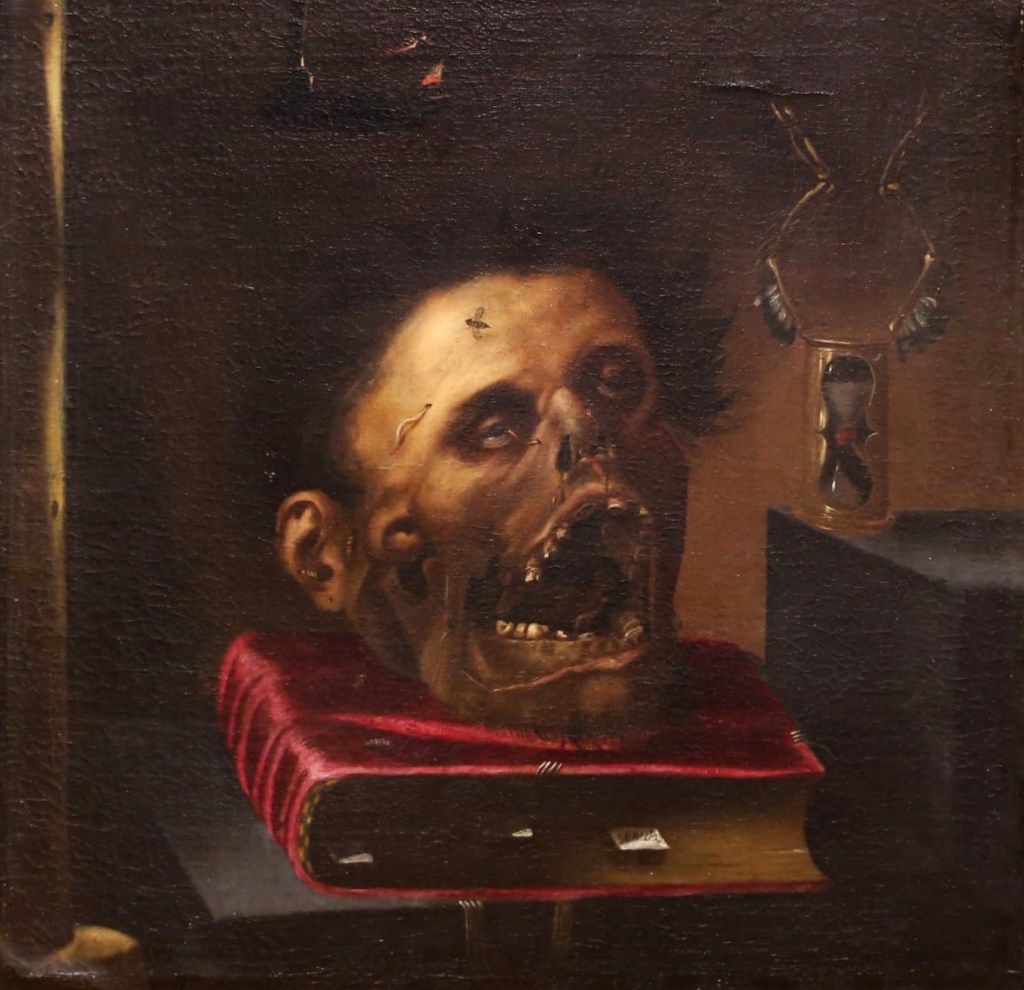

The stylistic genesis of these aforenoted works also suggests a visual literacy that extends into the darker recesses of Seicento painting. One can discern a compelling aesthetic kinship with the Lombard painter Francesco Cairo, whose morbid Baroque compositions centered on the agonizing threshold between life and death (fig. 11). Cairo’s penchant for depicting the physical paroxysm—the rolled-back eye, the slackened jaw, and a sallow, sickly chiaroscuro—finds a three-dimensional parallel in the Master’s early waxes. Furthermore, the Master likely possessed a familiarity with Jacopo Ligozzi, whose meticulous rendering of the transition from flesh to bone provided a precedent for the clinical vanitas (fig. 12). This dual influence—Cairo’s emotional morbidity and Ligozzi’s cold, drafted precision—allowed the Master to craft an oeuvre that functioned as both a visceral religious warning and a sophisticated document of human dissolution.

Fig. 11: Detail of Salome with the Head of John the Baptist by Francesco Cairo, ca. 1634-35, oil-on-canvas (Galleria Sabauda, Turin Italy)

Fig. 12: Vanitas by Jacopo Ligozzi, ca. 1600-27, oil-on-canvas (Labirinto della Masone di Franco Maria Ricci, Fontanellato, Italy)

Certainly, the influence of Gaetano Zumbo is ever-present. However, to differentiate the Scandalosa Master from Zumbo is to distinguish the “Theatre of Time” from the “Theatre of the Hospital.” Zumbo’s work maintains a Medicean elegance; his corpses are often beautiful in their decay, with classical forms and matte qualities.22 The Scandalosa Master, however, is a master of the incurable. His work is wet, his bones are pitted with infection, and his subjects are individualized. This differentiation is essential for proper art-historical attribution. The Christie’s example, mistakenly attributed to Zumbo, betrays the Master’s hand in its dental recession and the moulage technique used on the exposed cervical vertebrae. Furthermore, the Master’s focus on terminal trauma—such as the frequently featured neck wound—points to his firsthand witness of the scaffold. This wound is the direct result of rope compression during execution, a grim detail the Master would have observed while serving the Bianchi della Giustizia.

Notably, the incorporation of the lizard and rat, as featured on La Donna Scandalosa, the Sicilian bust and Longari bust, represents a choreographed theological ecosystem that functioned as a visual extension of the Bianchi della Giustizia’s rituals. The specific distribution of animals across the Scandalosa Master’s oeuvre may have functioned as a theological grading system. The Donna Scandalosa, with her quartet of scavengers (three rats, one lizard), represents the total collapse of the moral ‘fortress.’ In contrast, the Longari bust—potentially a cleric given the specific nature of his baldness—features the moth, a symbol of the internal corruption of sacred treasures. This suggests a taxonomy of sin: where the moth consumes the hidden spiritual life of the cleric, the rats of the Donna Scandalosa consume the public ‘windows’, or eyes, of the prostitute. This indicates the master did not apply these insects haphazardly but tailored the infestation to the specific social and moral identity of the subject.

Within the context of the confortoria, these animals mirrored the intense spiritual combat of the “Hour of Mercy,” where the confraternity utilized the Pratica di aiutare a ben morire (the Practice of Helping to Die Well) to secure the repentance of the condemned. The Master’s realism suggests he relied on the direct observation of bodies decaying within the hospital’s terraggio—the communal burial pit. This visceral engagement provided the clinical data for the Master to illustrate the “Predica della Casa Diroccata” (The Sermon of the Dilapidated House), a metaphor comparing the body to a ruined dwelling. These works effectively “illustrated the preacher’s words,” making these sculptures a silent, permanent sermon for the illiterate. The popularity of this sermon, codified in the 1724 Neapolitan manuals, provides a compelling terminus post quem for dating these busts. The sermon follows (translated from the 18th-century manuals):23

“Look now, oh soul, upon the vessel you once adorned with silks and perfumes. See how the Master of Truth [Death] now serves as your architect. On the left, where you harbored the fires of your worldly passions, the lizard of the earth now crawls. It seeks the heat that has fled from your cold limbs, a reminder that your flesh is but a stone in the field, a dwelling for the silent creatures of the dust. On the right, where you thought to store your riches and your pride, the gnawing guest [the rat] has arrived. He proves that the ‘right hand’ of your strength was but a shadow. Your eyes, which were once the windows of scandal, are now the doors for the worm. Your skin, once a veil of white linen, is now the soil of the grave. Repent, for the house is falling, and only the guest who flies [the soul] can escape the ruins.”

In conclusion, the Scandalosa Master emerges as a definitive, if still anonymous, force in Neapolitan ceroplastics. By assembling these works, we can see the beginnings of a cohesive oeuvre that functions as a “Pathological Map” of Neapolitan society. From the de-frocked cleric in the Longari bust to the noble figure in red silk, and finally to the “Scandalous Woman” in her infirmary linens, the Master’s work demonstrates that the biological reality of the Incurabili was the great social leveler. This master was the visual voice of the Bianchi della Giustizia, an artist who used clinical observation to craft a narrative of sin, decay, and redemption—one where every stratum of society is eventually unified by the same “gnawing guests.” His work remains the final evidence of a period that viewed the human body as a “dilapidated house,” and his hyper-realism, characterized by rooted hair, a liquefactive aesthetic, and fossilized linens, remains the signature of a hand that saw the truth of death more clearly than any of his contemporaries.

Endnotes

1 Andrea Daninos (2023): Gaetano Giulio Zumbo: 1656-1701. Officina Libraria, Rome.

2 Ibid. See also Jane Eade (2013): The Theatre of Death in Oxford Art Journal, Vol. 36, No. 1, pp. 109-125 and Regina Deckers (2019): Frightening Fragments: The Representation of the Corpse in Baroque Sculpture. The Morbid Anatomy Online Journal. April 25, 2019 (accessed January 2026). patreon.com/cw/morbidanatomy

3 Vittorio Sgarbi (2015): exh., Arte ceroplastica barocca a Catanzaro. Le cere di Caterina De Julianis.

4 Rose Marie San Juan (2013): Contaminating Bodies: Print and the 1656 Plague in Naples in New Approaches to Naples c. 1500–c. 1800. The Power of Place. Burlington, VT, Ashgate, pp. 63-78.

5 Regina Deckers (2013): La Scandalosa in Naples: A Veristic Waxwork as Memento Mori and Ethical Challenge in Esthetics of High-Decay. Rome, Max Planck Institute, pp. 75-91.

6 The confraternity was also alternatively addressed as the Compagnia della Buona Morte.

7 Girolamo Mascia (1972): La Confraternita` dei Bianchi della Giustizia a Napoli. S. Maria succurre Miseris. Convento San Francesco al Vomero, Naples; Ugo Di Furia (2010): I Bianchi della Giustizia: Notizie inedite su artisti ed opere di fabbrica in L’ospedale del Reame, Naples.

8 This notion is intimated in Cristiana Bastos (2017): Displayed Wounds, Encrypted Messages: Hyper-Realism and Imagination in Medical Moulages in Medical Anthropology: Cross-Cultural Studies in Health and Illness, no. 36:6.

9 While the present author links the invention of La Donna Scandalosa directly to the confraternity the idea that the artist may have alternatively been associated with the activity of one of the surrounding nunneries is not without merit, as initially suggested by Deckers.

10 Salvatore Di Giacomo (1914): Luci ed ombre napoletane. Naples, Perrella.

11 Antonio Illibato (2004): La compagnia dei Bianchi della Giustizia. Note storiche-critiche e inventario dell’archivio, Naples.

12 Francesco Redi (1668): Esperienze intorno alla generazione degl’insetti. Florence.

13 The bust was donated to the museum by Maria Grazia De Lanni, in memory of Ernesto Cilento. Prior to this, it was with the art dealer, Walter Padovoni, in his Milan gallery.

14 The artwork was formerly with Longari Arte in Milan and was attributed to Gaetano Zumbo with expertise provided by Paolo Giansiracusa, 7 January 2015. See also Bertolami Fine Art auction, 7 December 2022, lot 348.

15 Bertolami Fine Art auction, 1 July 2025, lot 301.

16 R. Deckers (2013): op. cit. (note 5).

17 Alfonso Maria de’ Liguori (1758): Apparecchio alla morte ossia considerazioni sulle massime eterne. Utili a tutti per meditare, ed ai sacerdoti per predicare, Naples, G. Di Simone.

18 Trionfante Antiques auction, 23 January 2026, lot 376.

19 Cambi casa d’aste, 11 December 2020, lot 95.

20 Afterwards, for a brief while in the present author’s collection, subsequently sold in London at Christie’s, Old Master Paintings & Sculpture, 9 July 2021, lot 232.

21 Christie’s auction, Sculpture et Objets d’Art Européens, Paris, 19 June 2018, lot 98.

22 Ronald Lightbown (1964): Gaetano Giulio Zumbo in The Burlington Magazine, UK.

23 La Predica della Casa Diroccata. See Giuseppe Raimondi (1724): Breve raguaglio del modo, col quale si assiste a’ condannati a morte nella città di Napoli. This sermon was a staple of the Jesuit and Redemptorist mission tradition in Naples, often used by the Bianchi to induce a ‘holy terror’ in the final hours of the condemned.

Leave a comment