by Michael Riddick

Preview / download PDF in High Resolution

The corpus of Nuremberg’s late Gothic and early Renaissance sculpture is frequently viewed through the lens of technical virtuosity; however, a profound tension underlies the celebrated “free arts” of this Imperial City. Nuremberg remained unique among its European peers for its draconian suppression of independent guilds following the failed Handwerkeraufstand or Craft Revolt of 1348.[i]

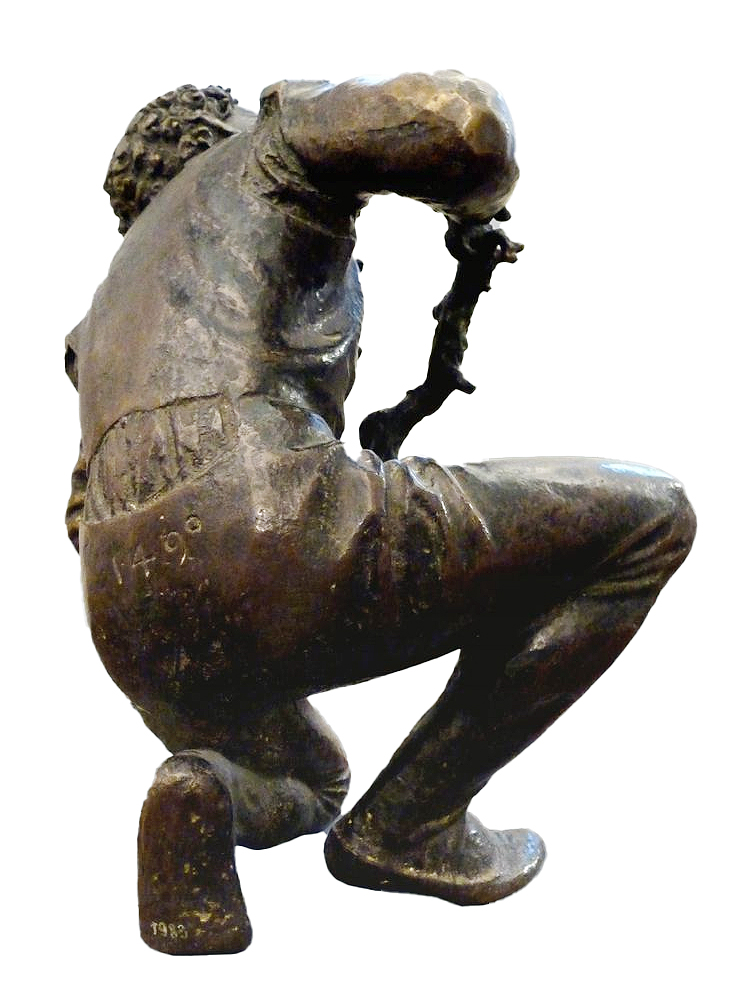

This essay proposes a radical reinterpretation of the bronze Branch-Breaker, a collaborative masterpiece traditionally attributed to the stonemason Adam Kraft and the bronze-caster Peter Vischer the Elder, dated 1490 (Cover, Figures). The present author suggests this figure—a muscular, kneeling craftsman in the throes of breaking a wooden limb—serves as a multi-layered allegory. It at once preserves the bitter memory of the 1348 insurrection and invokes the classical precedent of Volero Publilius, the Roman centurion whose defiance of the consular lictors and their scourging rods became a foundational narrative for 15th-century humanists.

Bronze Branch-Breaker, attributed to Adam Kraft (sculptor) and Peter Vischer the Elder (bronze caster), 1490 (Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, inv. MA 1983)

The very genesis of the Branch-Breaker is a provocation against the Nuremberg Council’s Rugamt, the administrative body governing the “Sworn Crafts.”[ii] The Council strictly forbid the formation of guilds to prevent the horizontal organization of labor. Yet, in the joint labor of Kraft and Vischer, we observe an “integral labor” that transcends the Council’s ethos.

The integration of Kraft’s sculptural sensibilities with Vischer’s metallurgical mastery represents a “silent guild” in practice. It is a work that could only be achieved through the mutual recognition of two masters whose trades were legally prevented from formal union. The sculpture thus becomes a monument to the unity of the crafts—a physical manifestation of the guild ideal that the 1348 martyrs had died to establish.

The 15th-century humanist circle in Nuremberg, led by figures such as Hartmann Schedel and Willibald Pirckheimer,[iii] was deeply immersed in the recovery of Livy’s Ab Urbe Condita. Central to Book II is the account of Volero Publilius, a former centurion who refused to be treated as a common soldier. When the consuls dispatched lictors to scourge him, Volero physically resisted, leading a plebeian surge that resulted in the breaking of the lictors’ fasces—the bundled rods of executive power.

The Branch-Breaker captures this exact moment of “fracturing authority.” The figure does not merely hold the branch; he subdues it with an anatomical intensity that recalls the classical Silenus, yet he is dressed in the garb of a contemporary German laborer. To a humanist viewer familiar with Livy, the snapping of the wood is not a rural chore, but a direct reference to the breaking of the lictor’s rods. It is an image of the dignitas of the veteran-worker asserting himself against the instruments of aristocratic correction.

Bronze Branch-Breaker, attributed to Adam Kraft (sculptor) and Peter Vischer the Elder (bronze caster), 1490 (Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, inv. MA 1983)

The 1348 Revolt ended in the execution and banishment of the city’s artisanal leaders, leaving the remaining craftsmen in a state of political subjugation. The “kneeling” posture of the sculpture is therefore double-edged. In one sense, it represents the “Atlas-like” strength required to sustain Nuremberg’s economy; in another, it mirrors the literal posture of the “Sworn Crafts” before the Patrician Council. However, by depicting the craftsman in the act of breaking the wood while in this submissive pose, Kraft and Vischer suggest that the potential for revolution is dormant but ever-present. The tension in the figure’s deltoids and the grimace of his facial expression—which reminisce of Kraft’s later self-portraits in the St. Lorenz Sakramentshaus[iv]—elevate the work from a mere “study from life” to a work of political theater.

The Branch-Breaker is perhaps the survivor of a lost discourse. It stands as a bridge between the Roman Republic’s ‘Conflict of the Orders’ and Nuremberg’s own stifled aspirations for self-governance. Through the shared labor of two of Nuremberg’s greatest artisans, the Branch-Breaker may have aspired to the reclaimed right of the craftsman to speak through his medium. It remains a testament to the fact that while the Nuremberg Council could ban the guild, they could not ban the allegorical power of the bronze itself, which continues to snap the rod of authority five centuries later.

[i] Ernst Mummenhoff (1910): Archivalische Zeitschrift. Das Bayerische Allgemeine Reichsarchiv in Munchen, pp. 1-124.

[ii] Jeffrey Chips Smith (1994): German Sculpture of the Later Renaissance c. 1520-1580: Art in an Age of Uncertainty. Princeton University Press.

[iii] William Wixom (1986): Gothic and Renaissance Art in Nuremberg 1300-1550, Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY.

[iv] Kraft’s famous self-portrait at the base of this monument—depicting himself and two assistants physically supporting the massive stone tower on their shoulders—has long been interpreted as a visual “complaint” or statement regarding the literal and social weight borne by the artisans in a city that refused them the protection of a guild.

Leave a comment