by Michael Riddick

Preview / download PDF in High Resolution

Fig. 1: (from top-left to bottom-right) Eight terracotta tondi of emperors and/or generals from the Medici bank in Milan (Castello Sforzesco, invs. 1541, 1538, 1539, 1536, 1542, possibly by Giovanni Battaggio [?], ca. 1490s, Milan; inv. 1540, possibly by Agostino Fonduli [?], ca. 1490s, Milan; invs. 1535, 1537, by an unknown author); Three terracotta tondi of emperors and/or generals from the Medici bank in Milan (Villa Cagnola, probably by Stefano Girola, ca. 1822-27)

The present author will aim to bypass the complex and ever-shifting terrain of attributions that characterize late 15th-century Milanese sculpture, selecting instead to focus on a specific, bewildering subject: the sculptural terracotta busts that once lined the façade of the Medici bank building in Milan (cover, fig. 1).

Cosimo de’ Medici established the Medici bank in Milan as both an expansion of his family’s economic empire and a crucial instrument of statecraft. The branch was designed to solidify a vital political alliance between Florence and the Duke of Milan, Francesco Sforza. This partnership was formalized in 1455 when Sforza demonstrated his commitment by donating the property required for the bank’s construction.1

While the influential Florentine architect Antonio Averlino, called Filarete, was actively engaged in Milan on major works like the Ospedale Maggiore, his possible participation in the bank’s design and construction remains unknown. The building’s patronage and oversight were managed by Cosimo’s appointed manager and resident, Pigello Portinari and Cosimo’s son, Giovanni di Cosimo de’ Medici, who selected the regional craftsmen responsible for the bank building’s redevelopment. Construction proceeded rapidly and the bank achieved functional completion around 1459 while the opulent decorative phase—including the elaborate marble portal and terracotta detailing—spanned a longer period, likely between 1455-63.2

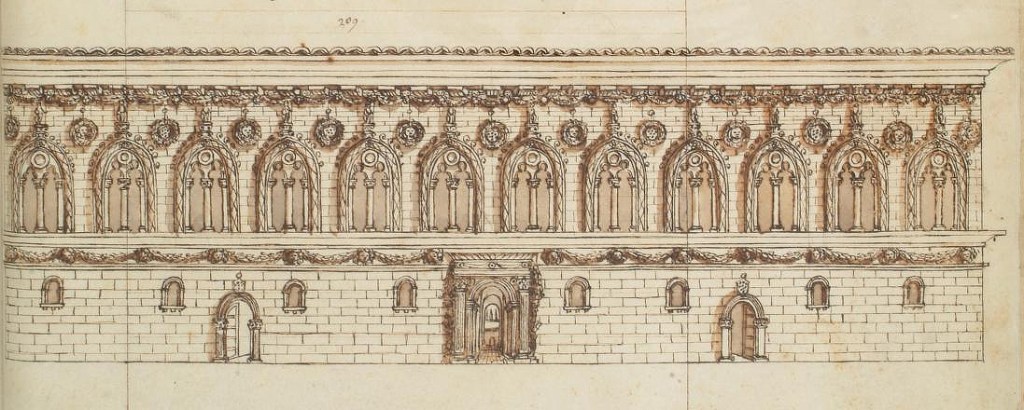

Fig. 2: Sketch portraying the facade of the Medici bank in Milan by Antonio Averlino, called Filarete, ca. 1461-64 (Codice Magliabechiano, Florence, Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, Fondo Nazionale, II.I.140, f. 192r)

The bank’s grandeur was recognized for its artistic and architectural importance shortly after its completion, described and sketched by Filarete in his seminal Treatise (fig. 2). His account offers an indication of the building’s innovative façade, articulated on two distinctive floors with an architectural elevation of stone and terracotta. The lower level featured a grand central portal rich with sculptural elements, a pair of flanking portals and a frieze of festoons, while the second level featured a series of intricate mullioned windows and a cycle of thirteen tondi.3

Thirteen tondi of varying quality, representing effigies of emperors or generals, were documented as present at the bank building during the early 19th century4 and eight are preserved today at the Castello Sforzesco (fig. 1, top 2 rows), along with twenty-eight additional fragments from the building’s façade. Other fragments are still known from photographic evidence but are yet-to-be located in the Castello Sforzesco collections.5 Three additional tondi have been recently located installed along the southern façade of the Villa Cagnola in Gazzada (fig. 1, bottom row),6 whilst two others were lost between 1827 and 1862.7

The chronology and attribution of these tondi is still unresolved8 but the present author desires to make some observations in following the complex timeline of the bank building’s varied tenants and owners and the intricate history of the tondi in association with the changes the building endured over centuries.

In Filarete’s sketch, ca. 1461-64, it appears the tondi alternate between seven tondi depicting the Medici coat-of-arms and six tondi of frontally facing busts or reliefs (fig. 2). It is typically assumed the suite of terracotta busts associated with the Medici bank were altogether conceived later, between 1486-89, when the Medici experienced a fiscal crises and FIlippo Eustachi acquired the building and soon thereafter sold it to his brother-in-law, Aloisio Terzaghi who invested 1,000 ducats to have it updated.9

However, Filarete’s sketch clearly depicts frontally facing heads already in situ along the bank’s façade as early as 1461-64. While we are tempted to assume the accuracy of Filarete’s depiction of the bank’s façade there are yet minor unexplained discrepancies between his rendering of its central portal and the presumed original marble portal which is preserved at the Castello Sforzesco (fig. 3). Nonetheless, we observe Filarete’s sketch portraying a relief program of alternating relief busts and Medici armorials which we generally accept as accurate.

Fig. 3: Marble portal of the Medici bank, 15th century, Milan (Museo d’Arte Antica, Castello Sforzesco, Milan)

It could be considered that upon the bank’s acquisition by Eustachi and Terzaghi, the seven tondi representing the Medici armorials were removed. This would align with Eustachi and Terzaghi’s power ambitions within the Sforza court to elevate their own influences and this idea is further stimulated by the sharp delegations between Eustachi and Lorenzo de’ Medici’s intermediaries in Eustachi’s aggressive acquisition of the property.10 Eustachi’s opportunistic determination in securing the bank building may have led to the decision to strip it of any Medici associations, thus resulting in the removal the Medici armorials, a possible fragment of which may survive in the form of a ‘studded shield’ in the Castello Sforzesco collections (fig. 4). The tondi portraying the Medici coat-of-arms were certainly removed by 1492 as adjudged by comments sent in a letter from the Florentine ambassador, Angelo Niccolini, to Piero di Lorenzo de Medici when the bank was subsequently reinhabited for a brief period by the Medici.11

Fig. 4: Terracotta fragment of a studded shield from the Medici bank, 15th century, Milan (Museo d’Arte Antica, Castello Sforzesco, Milan)

If the seven armorial tondi of the Medici arms were removed ca. 1486-89, did this also entail the removal of what may have originally been an additional series of six busts or reliefs as shown in Filarate’s sketch, or would these six tondi busts have been retained along the building’s façade with only the armorials being removed? This observation could infer at least six of the surviving busts may date to the early 1460s although this seems improbable based on the style of the busts which do not have any relationship to the sculptural milieu of Milan at-the-time. A scientific examination of the clay materials used on the surviving fragment presumably representing the Medici coat-of-arms, compared against the surviving antique tondi, might help resolve whether some of the surviving busts were original to the building as early as the 1460s or if they were made two or three decades after the installation of the bank’s original façade.

What is most certain is that both Eustachi and Terzaghi collectively collaborated in the restoration and reconstruction efforts of their respective properties: the Medici Bank building and the Palazzo Eustachi at Porta Vercellina, acquired by Eustachi only months before his acquisition of the Medici bank building.12 This observation, along with Terzaghi’s previously noted investment of 1,000 ducats in unspecified restorations to the building has led scholars to unanimously accept the terracotta tondi date to this phase of the building’s history, ca. 1486-89.13 Further encouraging this idea is the Palazzo Eustachi’s dependence on the avant-garde architectural characteristics and similar use of materials observed on the Medici bank which evidently influenced the Palazzo Eustachi’s design, including the use of tondi featuring terracotta busts which once formed part of its exterior.14

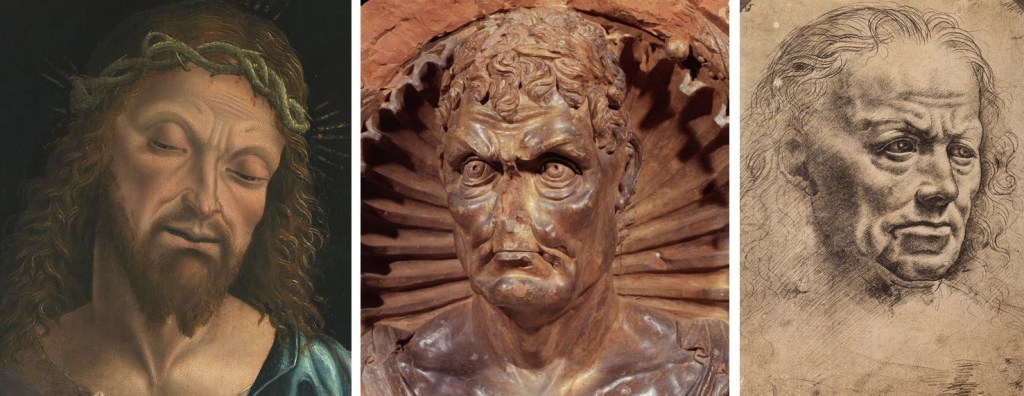

Three of these busts from the Palazzo Eustachi survive and in the present author’s opinion, they challenge the idea the Medici bank busts were conceived during this period. The three surviving busts preserved from the Palazzo Eustachi (fig. 5) do not stylistically relate to the Medici bank tondi and we may ask that if Eustachi was involved—directly or tangentially—in the commissioning of the Medici bank tondi, why are they so eccentric in comparison with those incorporated with his own palace project of the same period?

Fig. 5: Three terracotta tondi busts from the Palazzo Eustachi, Milan, here attributed to Agostino Fonduli, ca. 1485-89 (Museo d’Arte Antica, Castello Sforzesco, Milan, invs. 1565, 1564 and 1566)

While the Eustachi tondi have not been properly studied or analyzed in any significant depth, they stylistically fall into a category that is more conventional and in-line with what we observe on other comparable buildings also influenced by the Medici bank’s original architectural program like the Palazzo di Manfredo Landi and Palazzo Fodri in nearby Cremona. The terracotta sculptor most notably associated with the tondi on these two buildings is Agostino de Fondulis.15 Indeed, the Eustachi tondi have already been loosely associated with Agostino,16 an attribution the present author agrees with. This notion further aligns with Piero Galloza’s early observation that the terracotta fragments of eagles once belonging to the Palazzo Eustachi share a consonance with Agostino’s workmanship.17 The Eustachi busts particularly relate to Agostino’s eight terracotta tondi busts for the sacristy of Santa Maria in San Satiro from 1483 (fig. 6) and his possible involvement in the Eustachi tondi would follow Schofield’s suggestion of Bramante’s influence on the Palazzo Eusatchi as early as 1485,18 being the architect with whom Agostino had collaborated with slightly earlier at San Satiro.19

Fig. 6: Terracotta tondo bust from the Palazzo Eustachi, Milan, here attributed to Agostino Fonduli, ca. 1485-89 (left; Museo d’Arte Antica, Castello Sforzesco, Milan, inv. 1565); terracotta tondo bust by Agostino Fonduli, 1483, Milan (right; Sacristy of Saint Mary at San Satiro, Milan)

Agostino’s production of the terracotta busts at San Satiro has led some scholars to attempt associating the Medici bank tondi with Agostino20 but the present author notes Agostino’s style is more tempered and almost caricature-like in expression. Although Agostino’s busts can occasionally be fierce in their expressiveness, they lack the gruesome—almost monstrous—exaggerated and realistic countenance of the Medici Bank busts. There are also stylistic discrepancies regarding the articulation of the depressor supercilii between the eyes and the way the Medici bank busts portray wrinkles using impressive modeling techniques in contrast to Agostino’s preference for incising the wet clay to delineate wrinkles.

While the artists involved in the Palazzo Eustachi restorations remain vague, we are aware of documentary evidence pointing to Terzaghi’s earlier employ of regional artists for his previous residence which involved the local painter Paolo Patriarchi and the engineer Bartolomeo della Valle who had also been active at San Satiro.21 Unfortunately, his employ of any sculptors is unknown.

While Agostino may have been involved in the execution of the tondi for the Palazzo Eustachi we are left to wonder if Agostino could have ever managed to produce any potential tondi for the Medici bank façade. The earlier façade components of the 1460s may have only been removed under Terzaghi’s tenure but not yet replaced before his expulsion following accusations and convictions of conspiracy in September of 1489, of which Eustachi was also subject when both were stripped of their properties.22

The Medici bank building was next granted to Ludovico il Moro’s legitimized daughter, Bianca Giovanna Sforza, and her promised husband, the condottiero, Galeazzo Sanseverino, who took up temporary residence in the building while waiting for the completion of his property in Borgo delle Grazie.23 Galeazzo had played an active role in the arrest of Eustachi and Terzaghi.24

As a patron-of-arts, it is possible that despite such a short or intermittent stay at the building, Galeazzo could have taken an interest in potential modifications to it. Even if not realized, ideas could have been proposed, perhaps realized later under the discretion of Galeazzo’s brother, Antonio Maria Sanseverino, who would become beneficiary of the building in 149525 after a brief return of the Medici through reconciliations initiated by Piero di Lorenzo de Medici in October of 149226 followed by a subsequent Medici exile in March of 1495.27

It is worth noting that during Galeazzo’s residence at the bank building he was actively commissioning both Bramante and Leonardo da Vinci for projects at his Borgo delle Grazie property and for pageantries involving his formal wedding of 1490.28 It is documented that Leonardo visited and stayed with Galeazzo as early as January of 1491,29 and it remains unclear whether this refers to a stay with Galeazzo at his Borgo delle Grazie property or a possible stay at the Medici bank building although the former is most often presumed in spite of being reduced to a construction site between 1489-92. During his documented visit with Galeazzo, Leonardo was designing festival arrangements for one of Galeazzo’s jousting competitions in honor of Ludovico il Moro, and his wife, Beatrice d’Este.30 It remains possible Leonardo, Bramante or both artists could have visited Galeazzo during his temporary residence at the bank building, perhaps offering insights or suggestions on its condition. If the tondi along the façade remained stripped and unreplaced it stands to reason that either artist may have had a role in suggesting replacements or referring artists in their circle who could have executed the tondi busts during the early 1490s or after Galeazzo’s brother, Antonio Maria, took over the residence in 1495.31 Bramante’s innovate use of terracotta, both architectural or decorative, would have offered ample resources to Galeazzo as would Leonardo who is documented for his delight in the art of modelling in clay and who—in a manuscript of the early 1490s—cited the many terracotta “heads of old men in relief” he had made (fig. 7).32

Fig. 7: Terracotta tondo from the Medici bank possibly by Giovanni Battaggio (?), ca. 1490s, Milan (left; Castello Sforzesco, inv. 1538); red chalk sketch depicting the Head of and Old Man by Leonardo da Vinci, ca. 1490, Milan (right; Louvre, inv. 2249, Recto)

A drawing in the Ambrosiana Library (fig. 8), signed by Leonardo’s pupil, Giovanni Francesco Melzi,33 features the notation: “August 14, 1510, first taken from relief,” and refers to one of Leonardo’s teaching principles expressed in the early 1490s that, “the painter must first train his hand by copying drawings of good masters, and once this training is done with the judgment of his teacher, he must then train himself by copying good reliefs.”34 Leonardo also wrote during this time that he had practiced “no less in sculpture than in painting, and that he achieved both to the same degree.”35 The master responsible for the tondi appears to have been familiar with Leonardo’s artworks and anatomical knowledge adjudged by the feature of the deeply sunken cheeks, protruding chins, sagging jowls and exaggerated sub-mental fullness between the chin and neck featured on the Medici bank tondi and indicating their author may have had a first-hand knowledge of Leonardo’s sculpted models like that copied by Melzi in the aforenoted drawing.

Fig. 8: Terracotta tondo from the Medici bank possibly by Giovanni Battaggio (?), ca. 1490s, Milan (left; Castello Sforzesco, inv. 1541); red chalk sketch depicting the Head of an Old Man in Profile Facing to the Right by Giovanni Francesco Melzi, 1510 (right; Biblioteca Pinacoteca Ambrosiana, Milan Cod. F. 274)

While the tondi are sculptures that cannot be easily homogenized with the period and region, it remains doubtful they would belong to Leonardo’s own hand on account of their difference in style from any of his firm pictorial works. Nonetheless, the advanced characteristics of the sculpted tondi do indicate Leonardo’s influence during his activity in Milan, shaping the artistic milieu of his contemporaries. As noted by Pietro Marani, there is a particular consonance between some of the extraordinary features of the Medici Bank tondi busts and the character of the facial types (fig. 9) realized by the Leonardo-inspired Master of the Pala Sforzesca36—now identified as Giovanni Angelo Mirofoli—active in Milan during the mid-1490s and who worked on paintings earlier at Milan’s cathedral in 1486, and at San Satiro under Bramante’s supervision as early as 1483.37

Fig. 9: Detail of a painted panel of Christ as Salvator Mundi by Giovanni Angelo Mirofoli, formerly called the Master of the Pala Sforzesca, ca. 1490-94, Milan (left; Fitzwilliam Museum, inv. PD.4-1955); terracotta tondo from the Medici bank possibly by Giovanni Battaggio (?), ca. 1490s, Milan (center; Castello Sforzesco, inv. 1541); Metal point sketch of a Head of a Man seen three-quarters to the right attributed to Giovanni Angelo Mirofoli (right; Louvre, inv. 2416, Recto)

If the tondi were commissioned during Galeazzo Sanseverino’s tenure at the bank building or his brother’s subsequent residence in the building after 1495, we might conclude the tondi could be the work of a yet-to-be-identified sculptor operating in the ambit of Leonardo and perhaps someone in the orbit of Mirofoli during the 1480s-90s. Michael Kwakkelstein has noted the probable use of Leonardo’s terracotta models by Mirofoli, indicating a potential affinity between sculptors and painters among the Leonardeschi.38

Another consideration for the association of the tondi with the Sanseverino brothers is due to their portrayal of fiercely articulated military generals or emperors. As condottieri, and on account of the legacy of their father— Roberto Sanseverino d’Aragona, called the “new Achilles”—the subject of war heroes would have been representative of their family heritage. If all thirteen tondi were commissioned collectively by the Sanseverino we might ponder if they represent the twelve paladins and their central leader, Charlemagne. We may note Galeazzo’s letters to Isabella d’Este in 1491 in which they exchanged views on the virtues of the paladin heroes Orlando and Rinaldo, for example.39 Galeazzo’s mentorship under the scholar and master-at-arms, Pietro del Monte, would have also stoked his interest in the legends of ancient war heroes.

Further encouraging a sponsorship of the busts under Sanseverino patronage is the often-overlooked investment after March of 1495 when Antonio Maria Sanseverino took ownership of the building and was granted 1,000 ducats to “have it treated as he wishes.”40 While it is unknown to the present author whether Antonio Maria was ever an art patron, his brother’s slightly earlier residence at the bank building may have been impetus for ideas or plans on its enhancement. However, the extent of any renovations implemented with this budget is unknown and Antonio Maria seems only to have briefly resided over the property, as Giuliano de Medici is presumably resident there in 149641 until the fall of the Sforza dynasty in September of 1499 when the invading French king assigned the property to Catellano Trivulzio.42

Little else is known of the bank’s history until we learn from a plaque preserved at the building which commemorates major renovations occurring in 1688 by its then owner, Count Barnaba Barbò.43 This project may have involved some restorative work on the tondi and their probable relocation to the bank’s courtyard. The presence of the tondi within the courtyard is certainly confirmed in 1791 when an edition of Giorgio Vasari’s Vite has a note by Venanzio de Pagave mentioning the “colossal terracotta heads (in the courtyard)…heavily corroded by time…are protruding from the wall between the arches and porticoes.”44 The building remained within the Barbò family until 1802 when it was sold to the councilor Agostino Pizzoli, who later ceded it in 1822 to Carlo Vismara. By 1855 it would become the possession of the Valtorta family.45

As discussed in detail by Vito Zani, the tondi were restored and perhaps some were altogether recreated by the sculptor Stefano Girola on behalf of the bank building’s owner, Carlo Vismara, between 1822-27.46 In 1827 the Milanese guide, Giuseppe Caselli notes the presence of thirteen busts, which had been restored by that sculptor.47

During the 1860s further major renovations to the building and its façade were made by Giovanni Battista Valtorta.48 In 1862 the tondi were removed from the bank’s courtyard and there were only eleven remaining at-this-time.49 Two must have been lost between 1827/41-62. Toward the end of 1862 the art dealer, Giuseppe Buslini, acquired the busts, selling eight of them in 1873 to what is now the Raccolte d’Arte Applicata of the Castello Sforzesco in Milan.50

It could be assumed the remaining three tondi of the eleven which survived are those that ended up at the Villa Cagnola, certainly after Buslini’s acquisition of the group. Confirming this is Carlo Bossoli’s painting which shows the absence of these busts along the villa’s southern façade in 1859, as noted by Zani.51 It could be presumed Buslini was unsuccessful in selling the three tondi to the museum on account of their recent authorship, excessive restorations, or lackluster condition. This would attest to Giuseppe Mongeri’s comments on how “seven or eight [busts], show the work of an older and more excellent hand than the rest.”52 Buslini may therefore have sold the final three busts not long after 1873. It would have likely been Carlo Cagnola who acquired them, being a prominent collector of the period whose interests and acquisitions remain preserved at the Villa Cagnola. The addition of the busts along the southern façade of the villa would have followed the completion of the romantic gardens he installed along the Western façade of the villa, completed around 1860.53

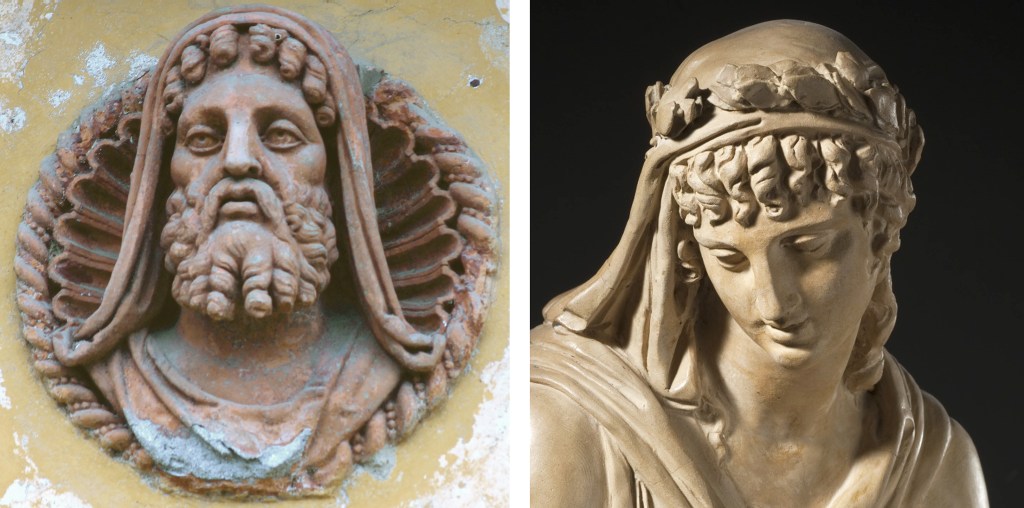

Fig. 10: Terracotta tondo of an old bearded man along the southern facade of the Villa Cagnola, Gazzada, probably by Stefano Girola, ca. 1822-27 (left); detail of a terracotta figure of an Allegory of Peace attributed to Camillo Pacetti (right; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, inv. M.80.44)

Zani has already pointed out the evident differences between the five restored tondi at the Castello Sforzesco (fig. 11) and the three that remain unrestored, still showcasing the various corrections, remodeling and perhaps reinvention applied to them. Zani particularly notes two busts which are especially new in appearance, both stylistically and in respect to their state of preservation (fig. 1, right-hand middle row).54 These latter two may correspond with the tondo of an old bearded man belonging to the suite preserved at Villa Cagnola (fig. 1, bottom row, left; fig. 10, left) whose apparent neo-classical manner is likewise already noted by Zani. It would be convenient for us to associate these three tondi with the restorations and possible reinventions imposed by Stefano Girola on behalf of his patron and the villa’s former owner, Valtorta. The effigies superficially relate to Girola’s other busts and statuary like his Virgil at the Palazzo Cavriani in Mantua and the series of busts that run along the gate of that same palace. The influence of Girola’s mentor, Camillo Pacetti, is suggestively evident in the Cagnola tondo of an old bearded man when compared against the terracotta Allegory of Peace attributed to Pacetti at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (fig. 10).

The group of three classically inspired tondi of Roman emperors or generals—one at the Castello Sforzesco55 and two at the Villa Cagnola56—comprises a potentially unique suite. These present challenges to understanding their true character on account of the extreme wear or restorative characteristics made to them. However, their thematic classicized features—notably distinct from their counterpart grouping of fiercely portrayed effigies—presents a congruence that would lead us to assume they too are altogether the invention of Girola or may have belonged to an alternate intervention, possibly due to Count Barbò’s renovations of the late 17th century with additional later restorations made by Girola. Their continuity of subject—presumably effigies of imperial Roman leaders—were less known in late 15th century Milan and popularized later through the diffusion of imagery derived from Titian’s Eleven Caesars although the impetus of these motifs can be traced back to the profile portraits of emperors popularized through the publication of Suetonius’ Lives of the Caesars in 1470.

Fig. 11: Five terracotta tondi from the Medici bank in Milan, possibly by Giovanni Battaggio (?), ca. 1490s (Castello Sforzesco, invs. 1541, 1538, 1539, 1536, 1542)

While the maker of the coherent, restored and confidently old Medici bank tondi busts have a shared yet-to-be identified author (fig. 11), a cursory overview of Quattrocento sculpture in Milan yields only one stylistic corollary in the work of Giovanni Antonio Piatti whose sole autograph and dated high-relief sculpture of 1478, depicting Plato, is preserved at the Casa Piatti. In accord with his contemporaries, Piatti was instrumental in the highly expressive sculpture emerging in Lombardy and Milan during the 1470s-80s when gothic sentiments gave way to burgeoning Renaissance styles.

The reconstruction of Piatti’s style is still questioned for a variety of reasons too complex to outline in this article,57 and I defer only to his singularly known autograph work. Like the Medici bank tondi, Piatti’s inventive fictional portrayal of a classical figure like Plato58 aligns with the equally fictive and inspired portraits of ancient heroes and emperors of the Medici bank busts.

Fig. 12: Terracotta tondo from the Medici bank possibly by Giovanni Battaggio (?), ca. 1490s, Milan (left, right; Castello Sforzesco, inv. 1541); detail of a stone relief depicting Plato by Giovanni Antonio Piatti, 1478 (center; Casa Piatti, Milan)

Stylistically, the best preserved tondo from the Sforzesco group, retaining most of its original composition, is readily comparable to Piatti’s autograph effigy of Plato (fig. 12). Especially commensurate is the fleshy character of the face wrapped around high cheek bones, the deeply set eyes, contorted brows which descend downwardly at a 45° angle, and the depressor supercilii along the center forehead which droops with a fleshy ridge above the nose in the manner of an eaves. The prominent orbital bags beneath the eyes as well as the pouted lower lip are likewise coeval. The treatment of the hair is similar, albeit, more easily rendered in the modeling of clay versus the chiseling of stone. The way the eyebrows rise and sharply curve along the brow line of Plato—terminating just ¾ in length above each eye—is also alike. Lastly, the exaggerated and deeply set nasolabial wrinkle descending beneath the nose is a feature observed on Piatti’s Plato and all five restored Sforzesco tondi.

Fig. 13: Detail of a marble relief sculpture depicting the Dead Christ Supported by Angels by Martino Benzoni, ca. 1468 (left; Walters Art Museum, inv. 27.198); terracotta tondo from the Medici bank possibly by Giovanni Battaggio (?), ca. 1490s, Milan (right; Castello Sforzesco, inv. 1539)

Some comparable features are also represented in one of Piatti’s earliest possible collaborators, Martino Benzoni,59 whose inventions hint at this same stylistic approach, particularly as concerns the articulation of the brow line, corrugator and procerus muscles above the nose (fig. 13). Benzoni—similar in age to Piatti—shares some stylistic idiosyncrasies, particularly observed in the earthy-vein riddled articulation of hands and in the coarse expression of their figures. Piatti collaborates again with Benzoni, and others, in executing the monument of Giovanni and Vitaliano Borromeo and documents indicate both artists were frequently in contact with one another.60 One could postulate whether they may have trained under the same master, presumably while actively working at the Milan Cathedral as teenagers.

It is certain Piatti involved himself in stone sculpture as evinced by the autograph Plato as well as the little documentary evidence concerning his career which firmly dates from 1468 until his death in February of 1480. Despite the apparent idiosyncrasies shared between Piatti’s autograph work and the terracotta Medici bank tondi, it is improbable the tondi would have involved Piatti. Foremost is that Piatti is not known to have worked in terracotta, and secondly, he was deceased six years before the bank building ever fell out of Medici hands. His age presents further problems, and though considered a master presiding over large commissions in his late 20s he would have only been 12-to-15 years old when Filarete sketched the Medici bank’s façade in his Treatise (fig. 2). Assuming Piatti could have made the tondi would be absurd if assuming the surviving tondi belonged to the original façade which they likely do not on stylistic grounds.

While Piatti’s direct connection with the prominent Piatti family of Milan is unestablished, we can however note a certain other Giovanni Piatti—an appointed deputy of the Ospedale Maggiore—who in April 1461, was tasked with his fellow deputy, Antonio Vimercati, to inspect and appraise the work executed by Filarete at the Ospedale Maggiore.61 As an administrative official for the city and the ducal court, Giovanni Piatti’s responsibilities were varied and his presumably close relative, a certain Giorgio Piatti, was also variably involved in lease and occupancy arrangements within the city and was intermingled with other local mercantile families like the Trivulzio and Colleoni and was himself a creditor to the Medici bank while under Pigello Portinari’s auspices.62 If the sculptor was an immediate relative, these potential family connections would have been instrumental in Giovanni Antonio Piatti’s earliest activity learning and working in the construction environment of the Milan Cathedral and elsewhere.

It could be presumed both stone carvers, Piatti and Martini, being of similar age, may have adopted their stylistic tendencies under the influence of a sculptor active at the cathedral or within the ambit of the various construction projects occurring in Milan at-that-time. While neither artist could be responsible for the Medici bank tondi since neither are known to have worked in terracotta, they may have been influenced by a common master and there were certain work environments within which stone masons and terracotta workers collaborated closely, beginning with the construction undertaken at the Ospedale Maggiore in 1457. Benzoni is certainly present at this project in 1463, executing work for two doors near the Navigli area of the complex.63 If Piatti is indeed related to the Ospedale Maggiore deputy of the same namesake, we could likewise assume Piatti worked in that same environment. Alessandro Barberie and Paola Bosio suggest a similar relationship among stone masons and terracotta workers in the construction efforts for the Medici bank in the late 1450s and early 1460s. The terracotta festoons and decorative elements of the bank are believed to have been conceived in the same working environment within which the bank’s marble portal was produced.64

One enigmatic character seemingly pervades all the themes reviewed thus far in this article, that is, Giovanni Battaggio da Lodi, best known for his accomplishments as an architect and engineer for the ducal court and whose work as a sculptor of terracotta is largely dismissed or unknown.65

Although Battaggio’s early activity is mostly a mystery, we find him working on terracotta fixtures and doors at the Ospedale Maggiore in 1465.66 It is possibly in the context of this vague early period that Battaggio may have had a role in influencing stone sculptors like Piatti and Benzoni. While this early period accentuates Battaggio’s focus on terracotta work his engagement in engineering follows in subsequent years when in 1479 he is appointed as official engineer for the city of Milan and in 1480 becomes the official ducal engineer, being a favorite of Ludovico il Moro.67

Traditional accounts, though unconfirmed, suggest Battaggio collaborated with both Bramante and Fonduli on the sacristy of San Satiro in the early 1480s.68 This professional relationship with Fonduli—who was destined to become Battaggio’s son-in-law—solidified into a formal partnership by 1484.69 The division of labor is clearly illustrated by the Palazzo Landi façade in the 1480s: Battaggio provided the overall design, while Fonduli executed the sculpted elements, notably its tondi busts (fig. 14).70 Battaggio’s distinct artistic style in these efforts is presumed to have been assimilated by his pupil, Fonduli, whose works should hint at a reflection of his master’s style.

Fig. 14: Terracotta tondo bust by Agostino Fonduli, ca. 1480s (Palazzo Landi in Piacenza)

Battaggio’s presumed activity at San Satiro as well as his efforts concerning the Milan Cathedral71 align with the previously discussed painter, Giovanni Angelo Mirofoli, whose presence at these locations could account for the possible reflection of what may have been Battagio’s influence over Mirofoli’s painted works (fig. 8). Battaggio would have also known Leonardo’s collaborator, Ambrogio de Predis who, along with Fonduli, lived near Battaggio in the Porta Ticinese area of Milan. Leonardo’s tenure at Ambrogio’s home when first arriving in Milan would have placed Leonardo in Battaggio’s immediate vicinity and Ambrogio’s later guarantee of the contract for Fonduli’s (and Battaggio’s) work at the Palazzo Landi confirm their probable amity.72 It could even be pondered if Leonardo’s elevated interest in terracotta modeling during his stay in Milan may be due to this early and on-going proximity with Battaggio and Fonduli.

By 1488 we are certain of Battaggio’s dual roles as both an engineer and a terracotta modeler as adjudged by the contract arrangements for the Chiesa dell’Incoronata in Lodi for which he provided architectural designs and “worked in terracotta, both by hand and with a mold,” a procedure which he again reiterated while initiating subsequent work on the Santa Maria della Croce in Crema in 1491.73 These documents firmly place Battaggio’s activity as a worker and modeler of terracotta from 1488-92, the time in which it is earlier suggested Galeazzo Sanseverino may have initiated a possible commission or plan for the execution of the Medici bank tondi.

Battaggio’s professional trajectory also directly intersected with Leonardo da Vinci’s during this precise moment in Milan around 1490, suggesting a shared intellectual environment and possibly a reciprocal involvement in the production of detailed architectural models. The most definitive evidence of their professional overlap occurred that year when both men—alongside Francesco di Giorgio Martini—competed for the prestigious and highly technical project of the Milan Cathedral lantern. Each submitted structural wooden models for review.74 If the Medici tondi busts are Battaggio’s workmanship, this could explain the character of Leonardo’s influence upon their design, being a moment-in-time when both artists were in collaboration.

The connection between Leonardo and Battaggio was intellectual as well as professional. Leonardo memorialized Battaggio in his personal writings, transcribing a philosophical observation directly attributed to the architect. In the Codex Atlanticus, under the date of 23 April 1490, Leonardo recorded Battaggio’s proverb: “If you want to teach someone something you don’t know, have him measure the length of something you don’t know, and he will know the length you didn’t know before.”75

This entry—recorded on a sheet marking the beginning of a major section of Leonardo’s notebooks—underscores a genuine intellectual dialogue between the two figures. The proverb itself emphasizes the two-way nature of specialized education, suggesting that the process of explaining a concept for absolute clarity yields new insights for the teacher as well as the student.

It is perhaps noteworthy or contextually coincidental that Leonardo’s sheet which documents his stay with Galeazzo Sanseverino in January of 1491 has a dated heading at its top margin which reads: 23 April 1490, being the same date in which Leonardo annotates and records the proverb by Battaggio, noted in the margin of a separate sheet within the codex, presumably an impulsive instance of note taking.

Battaggio emerges as a pivotal, if enigmatic, figure in the network of relationships that may theoretically have led to his creation of the terracotta busts for the Medici bank façade. Though primarily lauded as an engineer and architect–a master of such high esteem and accomplishment that the ducal court revered him, and documents referred to him as ‘the Milanese’ despite his Lodigiano roots.76 While his architectural achievements are recognized, we are left to speculate about his sculptural output, looking to figures like his pupil Fonduli for contextual links to the Medici tondi, which have, at times, been loosely associated with that artist. The Medici tondi, therefore, could be our only surviving testament of a gifted master’s work, a talent nurtured by burgeoning Renaissance ideas and the profound influence of a contemporary like Leonardo da Vinci.

Assuming Battaggio’s possible authorship of the Medici bank tondi would not only enrich our understanding of his diverse talents but also underscore their exemplary status in Milanese art, echoing Giuseppe Bertini’s discerning judgment that Battaggio was “the most interesting architect active in Lombardy during the last quarter of the 15th century aside from Bramante.”77

Endnotes:

1 Roberta Martinis (2003): Il palazzo del Banco Mediceo: edilizia e arte della diplomazia a Milano nel XV secolo in Annali di architettura. Rivista del Centro internazionale di Studi di Architettura Andrea Palladio di Vicenza, pp. 37-57; R. Martinis (2021): Anticamente moderni. Palazzi rinascimentali di Lombardia in eta sforzesca. Quodlibet Studio.

2 Ibid.

3 Antonio Averlino detto il Filarete. Trattato di architettura, ex. cat., curated by A.M. Finoli and L. Grassi, I-II, Milan 1972, pp. 698-704.

4 Giuseppe Caselli (1827): Nuovo ritratto di Milano in Riguardo alle belle arti, Milano, p. 202; Giulio Ferrario (1843): Memorie per servire alla storia dell’architettura milanese, Milano, p. 64; Luigi Zucoli (1841): Descrizione di Milano e de’ principali suoi contorni, Milano, p. 101; Ferdinando Cassina (1844): Le fabbriche più cospicue di Milano, Milan, tavv. 13-14; Giuseppe Mongeri (1862): La porta di via de’ Bossi in Milano, in La Perseveranza, 5 December; G. Mongeri (1864): Un’ultima parola intorno alla porta dei Bossi, in La Perseveranza, 27 January; Jaynie Anderson (1994): Giovanni Morelli museologo del Risorgimento, in Giovanni Morelli collezionista di disegni. La donazione al Castello Sforzesco, a cura di G. Bora, Cinisello Balsamo, pp. 29-30, et al.

5 Laura Basso, Alessandro Barbieri, Paola Bosio, Marilena Anzani and Alfiero Rabbolini (2012): Lavori in Corso al Museo d’Arte Antica di Milano. Le terreotte rinascimentali: studi, scoperte e restauri in Terres cuites de la Renaissance: matière et couleur, Technè, no. 36, pp. 92-101; Alesandro Barbieri and Paola Bosio (2011): Il cantiere delle terrecotte nel Museo d’Arte Antica del Castello Sforzesco attività di ricerca e primi risultati in Terrecotte nel Ducato di Milano. Artisti e Cantieri del Primo Rinascimento. Milan, pp. 195-239, fig. 3, p. 201.

6 Vito Zani (2014): Tre inediti medaglioni in terracotta e gli spolia del Banco mediceo di Milano. AntiquaNuovaSerie.it (accessed September 2025).

7 Adjudged by documentary evidence presented in G. Caselli (1827): op. cit. (note 4) and G. Mongeri (1862): op. cit. (note 4).

8 Elena Caldara (2003): Il Banco Mediceo di Milano e Castiglione Olona: un legame possible in Solchi, 1-2, pp. 1-14.

9 Archivio di Stato di Modena, Cancelleria Ducale, Carteggio Ambasciatori Estensi, Milan, b. 7. Giacomo Trotti to the Duke of Ferrara, 1492 May 15, Milan, in Roberta Martinis (2008): L’architettura contesa. Federico da Montefeltro, Lorenzo De Medici, gli Sforza e palazzo Salvatico a Milano, Mondadori, Milano, p. 12. See also Edoardo Rossetti (2005-06): L’incompiuto palazzo del castellano Filippo Eustachi a Porta Vercellina, in Archivio storico lombardo, s. XII, XI, pp. 431-61 and Matteo Ceriana and Edoardo Rossetti (2015): I baroni per Gaspare Ambrogio Visconti in Donato Bramante, da Urbino a Milano: Pittura, miniatura, scultura. Milan, Skira, pp. 196-97, 365-66; R. Martinis (2003): op. cit. (note 1), Appendix, doc. 12, p. 52; and A. Giulini (1912): Bianca Maria Sanseverino Sforza, figlia di Ludovico il Moro in Archivio storico Lombardo, XXXIX, pp. 233-52.

10 E. Rossetti (2005-06), ibid. and R. Martinis (2003): op. cit. (note 1), p. 39, Appendix, doc. 3, p. 50.

11 Fondo Mediceo avanti il Principato, LXXIV, 15, 27 November 1492.

12 See endnote 10.

13 See endnote 9.

14 E. Rossetti (2005-06): op. cit. (note 9); M. Ceriana and E. Rossetti (2015): op. cit. (note 9).

15 Luca Giordano (1990): L’architettura, 1490-500 in La basilica di S. Maria della Croce a Crema. Crema, pp. 42-45 and footnotes on pp. 53-55; Maria Luisa Ferrari (1974): Ilraggio di Bramante nel territorio cremonese: Agostino De Fonduli in Studi bramanteschi, Atti del Congresso, Rome, pp. 223-32. Although generally accepted, Fondulis’ activity at the Palazzo Landi is less secure but is inferred by several documents. Giorgio Fiori (1967): Le sconosciute opere piacentine di Guiniforte Solari e di Gian Pietro da Rho. I portali di S. Francesco e di palazzo Landi in Archivio Storico Lombardo, Series 9, Vol. 6, p. 139.

16 M. Ceriana and E. Rossetti (2015): op. cit. (note 9); Aldo Galli (2019): Agostino de Fonduli: all’Antica Head in A Taste for Sculpture, VI. Brun Fine Art, London, pp. 6-17.

17 Piero Gazzola (1939): La casa dei Medici in porta Vercellina a Milano in Atti del IV convegno nazionale di Storia dell’Architettura, Milan, pp. 153-62.

18 Richard Schofield (2016): Bramante and the Palazzo Eustachi in Early Modern Italy and Europe. Models and Languages. Viella, Rome, pp. 262-87.

19 R. Martinis (2021): op. cit. (note 1), pp. 587-88.

20 Elena Caldara (2002): Medaglioni con teste virili in G. Agosti, M. Natale and G. Romano, eds., Vincenzo Foppa: Un protagonista del Rinascimento. Milan, p. 145; various authors (2005): Medaglione con busto di imperatore e Medaglione con busto virile, in La Pinacoteca del Castello Sforzesco a Milano, curated by L. Basso and M. Natale, Milan, pp. 56-59. For the relationship to Fondulis see Sandrina Bandera (1997): Agostino de’ Fonduli e la riscoperta della terracotta nel Rinascimento Lombardo. Crema, pp. 41-42. In the present author’s opinion, the only surviving Medici bank tondo that could stylistically relate to Fondulis’ hand might be the bust of a Roman emperor preserved at the Castello Sforzesco (inv. 1540).

21 E. Rossetti (2005-06): op. cit. (note 9).

22 Nadia Covini (1993): Filippo Eustachi in Dizionario biografico degli italiani, vol. 43, Rome, Istituto dell’Enciclopedia italiana, p. 538.

23 Archivio di Stato di Firenze, Fondo Mediceo avanti il Principato, b. 50, l. 163, Pietro Alamanni to Lorenzo de Medici, dated 18 September 1489.

24 Roberto Damiani: Entry on Galeazzo Sanseverino from Condottieri di Ventura, condottieridiventura.it (accessed September 2025)

25 Archivio di Stato di Modena, Cancelleria Ducale, Carteggio Ambasciatori Estensi, Milano, b. 9, Giacomo Trotti al Duca di Ferrara, Milano, 12 March 1495; and Archivio di Stato di Milano, Sforzesco, Milano città, 1120, Il duca a Bartolomeo Calco, Vigevano, 20 March 1495.

26 R. Martinis (2003): op. cit. (note 1).

27 Ibid. See also endnote 25.

28 Edoardo Rossetti (2021): Milano, Palazzo Sanseverino alle Grazie. SUPSI, neorenaissance.supsi.ch (accessed September 2025); Martin Kemp and Pascal Cotti (2010): La Bella Principessa. Hodder & Stoughton, pp. 79-80.

29 Arundel Codex, c. 250r, dated 26 January 1491. See also Francesco Malaguzzi Valeri (1867): La corte di Lodovico il Moro: la vita privata e l’arte a Milano nella seconda metà del Quattrocento. Milano, 1913 ed., p. 556.

30 Ibid.

31 See endnote 25.

32 Edoardo Villata (2018): Some Notes on Leonardo da Vinci as a Sculptor in Leonardo da Vinci & the Budapest Horse and Rider. Budapest Museum of Fine Arts, pp. 73-91; E. Villata (2011): Leonardo plastiatore tra Firenze e Milano: proposte di metodo e di attribuzione in Terrecotte nel Ducato di Milano. Artisti e Cantieri del Primo Rinascimento, pp. 271-87. The text is documented in the Codex Atlanticus, Augusto Marinoni (2000): Leonardo da Vinci, II Codice Atlantica della Biblioteca Ambrosiana di Milano. 3 vols, Florence, fol. 888r (324r).

33 Ambrosiana Library, Codice F 274 inf. 8.

34 ‘Il pictore debbe prima suefare la mano col ritrarre disegni di mani di bon maestro, e fatta detta suefationi, col giuditio del suo precettore, debbe di poi suefarsi col ritrarre cose di rilievo bone con quelle regole che di sotto si dirà.’ Formerly Ms. Bibliotheque Nationale, Institut de France, Paris, 2038, fol. 10a; see Jean Paul Richter (1970): The Literary Works of Leonardo da Vinci, 3rd ed., New York, vol. 1, p. 303, no. 485.

35 ‘[…] non meno in scultura che in pittura, et essercitando l’una e l’altra in un medesimo grado’, Ibid., fol. 25a; see J.P. Richter (1970): op. cit. (note 34), vol. 1, p. 369, no. 655.

36 Pietro Marani (1988): Maestro della Pala Sforzesca in Pinacoteca di Brera. Scuole lombarada e piemontese 1300-1535. Milan, pp. 325-30.

37 Antonio Mazzotta (2022): Alcuni indizi per l’identificazione del ‘Maestro dell apala sforzesca’ in Prospettiva, pp. 78-85.

38 Michael Kwakkelstein (2003): The Use of Sculptural Models by the Master of the Pala Sforzesca in Raccolta Vinciana, vol. 30, pp. 149-78.

39 The letters are preserved in the State Archives of Mantua. See also Julia Cartwright (1945): Beatrice d’Este, Duchessa di Milano. Milan, Edizioni Cenobio, pp. 75-87.

40 Archivio di Stato di Modena, Cancelleria Ducale, Carteggio Ambasciatori Estensi, Milan, b. 4, Giacomo Trotti to the Duke of Ferrara, Milan, 23 February 1486.

41 R. Martinis (2003): op. cit. (note 1).

42 Ibid.

43 Vincenzo Forcella (1892): Iscrizioni delle chiese e degli altri edifici di Milano, vol. X, Milan, p. 107, n. 123.

44 Gian Alberto Dell’Acqua (1983): Le teste all’antica del Banco Mediceo a Milano, in Paragone, 34, pp. 48-55, see p. 49.

45 C. Casati (1885): Documenti sul palazzo chiamato “Il Banco Mediceo in Archivio storico lombardo, series 2, XII, p. 588.

46 V. Zani (2014): op. cit. (note 6); in G. Caselli (1827): op. cit. (note 4), p. 202; G. Ferrario (1843): op. cit. (note 4), p. 64.

47 Ibid.

48 G. Mongeri (1862): op. cit. (note 4).

49 Ibid.

50 G. Mongeri (1864): op. cit. (note 4).

51 V. Zani (2014): op. cit. (note 6); see also Miklòs Boskovits and Giorgio Fossaluzza (1998): La collezione Cagnola. I dipinti dal XIII al XIX secolo. Busto Arsizio, p. 244, cat. 98.

52 G. Mongeri (1862): op. cit. (note 4).

53 Villacagnola.com

54 Castello Sforzesco, invs. 1535 and 1537.

55 Castello Sforzesco, inv. 1540.

56 Both are located along the portico wall of the Villa Cagnola’s southern façade.

57 A discussion that touches upon the troubles in defining Piatti’s style is presented in Mirko Moizi and Andrea Spiriti (2023): Scultori dello Stato di Milano (1395-1535), Accademia di architettura, Mendrisio, Universita della Svizzera italiana, pp. 7-28, see particularly pp. 17-19.

58 Ulrich Pfisterer calls attention to this and suggests Piatti’s effigy of Plato may have also served as a self-portrait. U. Pfisterer (2022): Plato in Mailand. Giovanni Antonio Piatti erschafft sich 1478 ein Denkmal in Viaggio nel Nord Italia in Studi in cultura visiva in onore di Alessandro Nova. Florence, pp. 288-92.

59 The earliest document possibly referring to Piatti involves the 1464 registers of Milan cathedral where he and the sculptor Martino Benzoni collaborated on stone carving. Federico Maria Giani (2010-11): Ricerche sull’altare di San Giuseppe nel duomo di Milano, tesi di laurea, Università degli Studi di Milano, p. 169.

60 Laura Cavazzini (2004): Il crepuscolo della scultura medieval in Lombardia. Florence, pp. 141-43.

61 Giuliana Albini (2011): Materiali per la storia dell’Ospedale Maggiore di Milano: le Ordinazioni capitolari degli anni 1456-1498 in Reti Medievali Rivista, 12, 1, University of Naples Federico II, Firenze University Press, pp. see Registro 2, c. 130, 643, documented 16 April 1461.

62 Nadia Covini (1998): L’esercito del duca: organizzazione militare e istituzioni al tempo degli Sforza, 1450-1480 in Nuovi Studi Storici, 42, pp. 431-55.

63 Pio Pecchiai (1927): L’Ospedale Maggiore di Milano in Storia e nell ‘arte, Milano, p. 455.

64 A. Barberie and P. Bosio (2011): op. cit. (note 5).

65 The two terracotta busts above the side portals of the Chiesa dell’Incoronata in Crema could be his work but this is not entirely certain. Antonio Gussalli (1905): L’opera del B. nella chiesa di S. Maria di Crema in Rassegna d’arte, V, pp. 17-21; Aldo Foratti (1917): L’Incoronata di Lodi e il suo problema costruttivo in L’Arte, XX, p. 219.

66 Gian Piero Borlini (1970): Battaggio, Giovanni, detto anche Giovanni da Lodi in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani – Volume 7, Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana fondata da Giovanni Treccani.

67 Ibid.

68 Ibid.

69 G. Fiori (1967): op. cit. (note 15).

70 Francesco Malaguzzi Valeri (1915): La corte di Ludovico il Moro.II. Bramante e Leonardo da Vinci, Milan, p. 252.

71 G.P. Borlini (1970): op. cit. (note 66); Battaggio’s activities involving the Milan Cathedral are expressed in letters exchanged between Ludovico il Moro and his brother, Ottaviano, during the early 1480s. Ducal Register, no. 118, c. 119.

72 Ibid.

73 E. Gussalli (1905): op. cit. (note 65).

74 Annali della fabbrica del Duomo di Milano, III, Milano 1880, p. 60 (27 June 1490).

75 ‘Se tu volli insegnare a uno una cos ache tu non sappia, falli measurare la lunghezza d’una cosa a te incognita e lui sapra la misura che tu prima non sapevi. – Maestro Giovanni da Lodi.’ Codex Atlanticus, ff. 75, 76v-b.

76 G.P. Borlini (1970): op. cit. (note 66)

77 Giuseppe Bertini (2010): Center and Periphery: Art Patronage in Renaissance Piacenza and Parma in The Court Cities of Northern Italy. Cambridge University Press, pp. 71-137.

Leave a comment