by Michael Riddick

Preview / download PDF in High Resolution

Preview Italian version at Antiqua Nuova Serie

Fig 1: A gilt bronze pax of the Virgin and Child, formerly in the collection of the Baron of Monville (Thomas Charles Gaston), by Moderno and probably cast by Moderno & Associated Makers, ca. 1528-35 (image courtesy De Gurbert Antiques, France; left); a colored maiolica pax of the Virgin and Child, after Moderno (Museo Civico di Modena, inv. 1437; center); a blue and cream maiolica pax of the Virgin and Child, after Moderno (Victoria & Albert Museum, inv. 635-1891; right)

A unique maiolica plaque based on a devotional pax representing the Institution of the Rosary was recently identified in the art market1 (fig. 4, right) and relates to another similar maiolica pax from the same workshop preserved at the Museo Civico di Modena (fig. 1, center) which reproduces a pax of the Virgin and Child by Galeazzo Mondella (called Moderno) (fig. 1, left).2 While the art market pax is painted only in light blue upon a cream base the Modena pax is dynamically painted in blue, yellow, green and burgundy. However, another example of Moderno’s pax, only in light blue on a cream ground, is preserved at the Victoria & Albert Museum (V&A) (fig. 1, right).3 The V&A’s receipt of this maiolica pax provides a terminus ante quem for its creation before 1891. The maiolica paxes made after Moderno’s pax appear to descend from the same workshop mould, adjudged by the upper suspension flange unique to these maiolica paxes and not present on examples of the original bronze examples known in various private and museum collections. A similarly styled suspension flange is also applied to the art market pax depicting the Institution of the Rosary, to be discussed and suggests an origin in the same maiolica workshop.

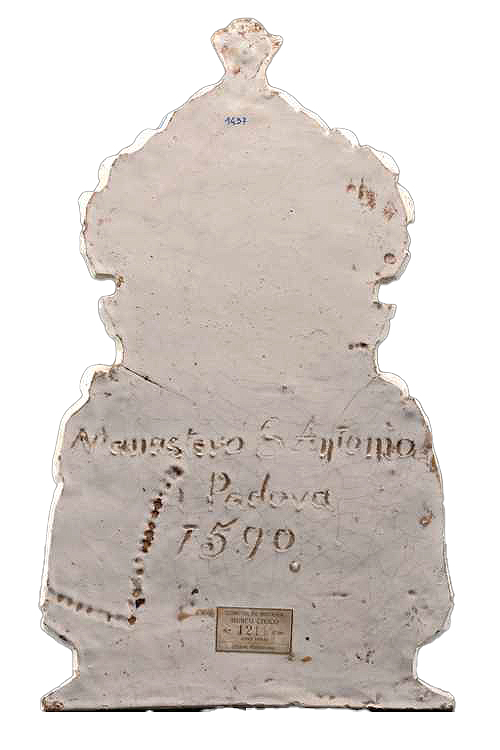

Fig 2: Reverse of a colored maiolica pax of the Virgin and Child, after Moderno (Museo Civico di Modena, inv. 1437)

The reverse of the Modena pax (fig. 2) features an inscription: Monastero S. Antonio / Padova / 1590, suggesting the origin of location for where the maiolica factory acquired its model: the Convent of Saint Anthony in Padua whose holdings include a quantity of other important works from the Renaissance and later periods, partitioned into various museums including the Antonian Museum established in 1895. The “1590” on the reverse of the maiolica pax is enigmatic. An immediate thought is that it could represent a possible date. The original pax by Moderno is thought to have been conceived in 14904 and as the present author has noted, was continually produced by his son and nephews between 1528-35.5 It is uncertain if the four-digit number refers to the year 1590 or possibly refers to an inventory number within the maiolica workshop responsible for its facture. If referring to a date, it is to be wondered if the pax itself was inscribed with this date, although only one dated example of this pax is presently known.6 It could alternatively relate to a documented year of receipt of the object in the monastery’s records but this seems less likely.

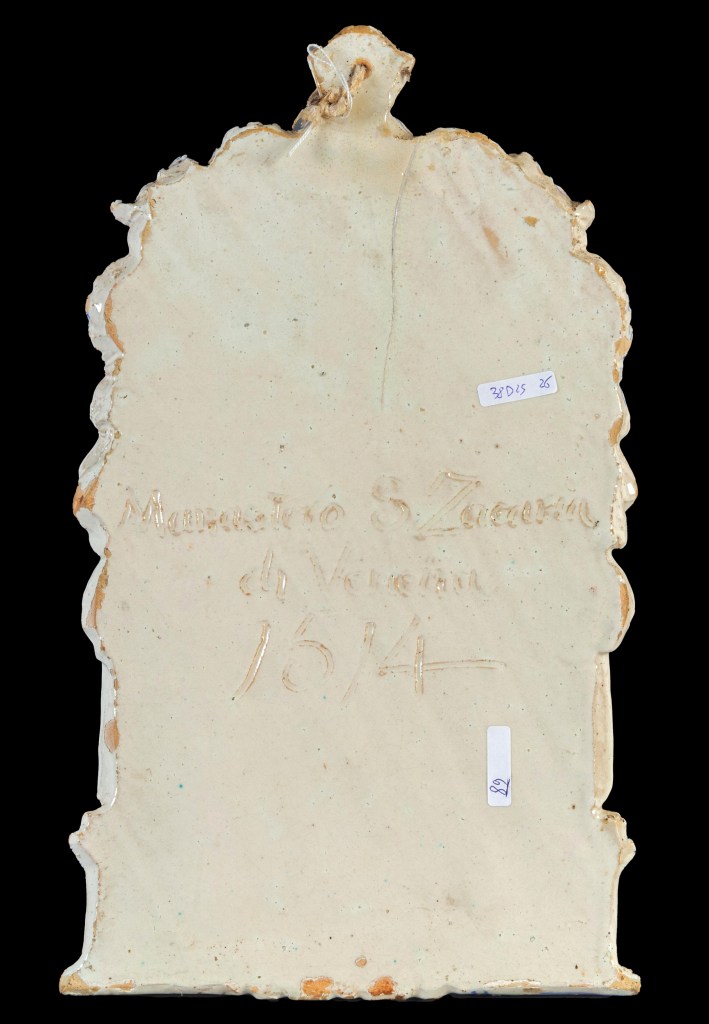

Fig 3: Reverse of an art market blue and cream maiolica pax representing the Institution of the Rosary (Aste Boetto, Italy, 17 June 2025, Lot 267)

Another pax depicting the Institution of the Rosary, previously mentioned, is scarcely noted in literature, and is also reproduced by this same maiolica workshop (fig. 4). The reverse of the maiolica pax features a similar inscription: Monastero S. Zacaria / di Venezia / 1614, referring to the Church of San Zaccaria in Venice (fig. 3). In lieu of what would otherwise be an empty blank ground on the lower surface of the relief, a coat-of-arms has been painted by the maiolica artist involved in its production and may possibly reference the Contarini family crest, one of the founding families of Venice.

Fig 4: A silver pax representing the Institution of the Rosary (Church of San Zaccaria, Venice; left); an art market blue and cream maiolica pax representing the Institution of the Rosary (Aste Boetto, Italy, 17 June 2025, Lot 267; right)

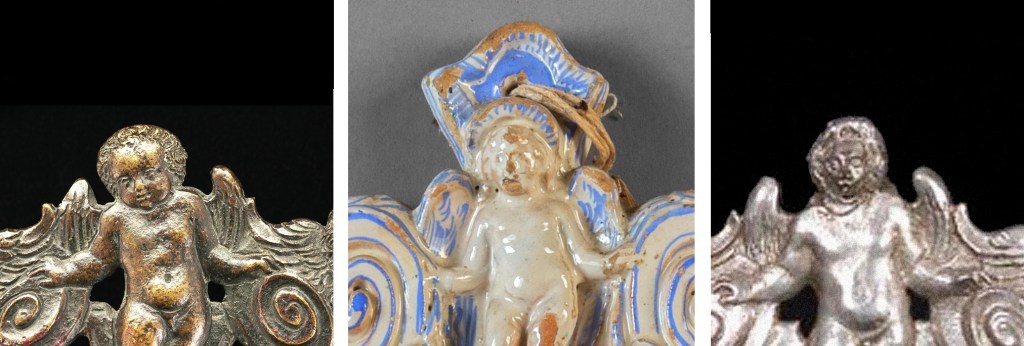

The original prototype for the maiolica version indeed survives in the Church of San Zaccaria in Venice, identified by a fine silver pax (fig. 4, left). Unlike the maiolica pax reproducing Moderno’s Virgin and Child, this maiolica pax depicting the Institution of the Rosary is partly taken from the original example at San Zaccaria and is partly remodeled freely by an artist active in the maiolica workshop. For example, the feature of the Virgin and child Christ have been reworked and are more diminutive in-scale while the capitals atop the columns are reworked as well as the winged putti along the frieze of their plinths. Nonetheless, a confirmation of the Zaccaria pax serving as a master model for the maiolica workshop is found in the unique head of the cherub atop the pediment of the pax whose characteristics are coeval with the maiolica version (fig. 5). The same head of the cherub is quite probably a later replacement on the silver original, possibly having broken off at some point in its history. The original design of the head of this cherub is featured on a bronze aftercast of the Zaccaria pax preserved at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC (NGA; figs. 5, left, and 6).7 The NGA pax features the same silhouetted characteristics of the original silver pax but adds intentional chasing to articulate the finer details that may have been lost in translation from being cast after the original model.

Fig 5: Detail of a bronze pax of the Institution of the Rosary (National Gallery of Art, DC, inv. 2002.102.2; left); detail of an art market blue and cream maiolica pax representing the Institution of the Rosary (Aste Boetto, Italy, 17 June 2025, Lot 267; center); detail of a silver pax representing the Institution of the Rosary (Church of San Zaccaria, Venice; right)

Fig 6: A bronze pax of the Institution of the Rosary (National Gallery of Art, DC, inv. 2002.102.2

While the frame is the unique invention of the silversmith probably responsible for the Zaccaria pax, the central composition—depicting the Institution of the Rosary—is adapted from an extant design that must have circulated in Venice during the last quarter of the 16th century. Evidence for this is observed in a much more commonly found variant of the relief in an alternative, probably contemporary, oval frame. This earlier version features more of the composition along its margins, which are otherwise lost on the silver Zaccaria pax. The composition is scarcely discussed in plaquette literature and to the present author’s knowledge, is only discussed in any depth by Charles Avery in citing an example at the Museo Civico di Amadeo Lia.8

Avery noted the composition’s feature of Mary handing a string of pearls to Saint Dominic, referencing that saint’s vision of the Virgin. The scene likewise features Saint Catherine of Siena who also is frequently associated with the rosary and who likewise is described as having experienced a vision of the Virgin. Avery wondered if the composition may have originally been commissioned by the Dominicans sometime after the Battle of Lepanto in 1571.9 During the late 15th and early 16th century the Monastery of San Zaccaria was occupied by a Benedictine order of nuns, suggesting they were not involved in the original commission of this composition but must have appreciated the extant design on account of their use of the rosary and dedication to the Virgin, thus prompting its possible feature on the Zaccaria pax.

While a quantity of examples of the Institution of the Rosary composition exists in ecclesiastic and private and public collections,10 the most remarkable cast of this relief was formerly with Julius Böhler and is today preserved at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (fig. 7). This example must be very close to the original prototype as it features an open ground in the upper portion of the scene which is modified on later casts like the winged putti heads flanking the upper portion of the Zaccaria pax or on later and more crude casts of the ovular version which feature integrated winged angels hovering above the scene.

Fig 7: An openwork bronze cast pax depicting the Institution of the Rosary, Venice, ca. 1575-1600 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, inv. 08.175.13)

While the silver Zaccaria pax probably dates to the early part of the 17th century,11 it is unknown if the numbers on the back of the maiolica version reflect a presumed date for its origin (1614). That the silver Zaccaria pax lacks any hallmarks or inscribed dates it must therefore be presumed that the numerals used on the maiolica workshop’s reproductions of these paxes most probably reflect internal workshop catalog or inventory numbers.

These interesting maiolica paxes may have an origin in the Emilia-Romagna region sometime during the last third of the 19th century, exhibiting the colors and detailed mouldings characteristic of the period’s revival of interest in this antique style of ceramic work.

Fig 8: Bronze plaquette of the Madonna with the Infant Christ and John the Baptist (John R. Gaines collection, Morton & Eden sale, 8 December 2005; left); colored maiolica holy water stoup depicting the Madonna with the Infant Christ and John the Baptist, Deruta, 17th century (Bonhams auction, 14 May 2008, Lot 22; right).

While these modern maiolica paxes are an outlier in the subject of plaquette literature it should be noted that other early examples of this practice exist like a painted maiolica pax reproducing Moderno’s Dead Christ Supported by Mary and John, probably made in Deruta during the 17th century. Two other popularly diffused plaquette reliefs were likewise translated in maiolica like a Pieta attributed to Jacobus Cornelis Cobaert, reproduced on two relief panels of a large glazed earthenware tabernacle preserved at Museo Castello del Buonconsiglio in Trento12 and an anonymous plaquette of the Madonna with the Infant Christ and John the Baptist, also reproduced in Deruta during the late 17th century for a maiolica water stoup (fig. 8). A similar treatment is witnessed on an 18th century Portuguese maiolica water stoup reproducing a well-circulated Spanish plaquette representing the Ecce Homo.13

Endnotes:

[1] Aste Boetto auction, 17 June 2025, lot 267.

[2] Museo Civico di Modena, inv. 1437.

[3] Victoria & Albert Museum, inv. 635-1891.

[4] Douglas Lewis (1989): The Plaquettes of ‘Moderno’ and His Followers in Studies in The History of Art, vol. 22, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, pp. 105–07 and Francesco Rossi (2006): Placchette e rilievi di bronzo nell’età del Mantegna, Mantova e Milano. Skira, no. 32, pp. 53-56.

[5] Michael Riddick (2023): Moderno & Associated Makers – A Partnership between Galeazzo Mondella’s Son and Nephews. Renbronze.com (accessed May 2025).

[6] A dated example with the year 1490, was in the collection of Alfred Higgins, offered at a Christies auction on 29 January 1904, lot 47 and purchased by the collector Paul Garnier.

[7] National Gallery of Art, DC, inv. 2002.102.2.

[8] Charles Avery (1998): La Spezia. Amedeo Lia Civic Museum. Sculptures, Bronzes, Plaques, Medals. CR La Spezia Foundation, p. 280, no. 199.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Another example is in the Berlin collections (inv. 1382) and others were in the private market including one formerly with the present author and others offered at Christies, 7 July 2015, lot 533 and Koller auction house around 2013-14. An extended variant of the relief in which the subject exchanges its elaborate frame for an integral stepped filet frame with a round suspension loop—popularly used in Spain by various provincial workshops—is known by an example at the Museo Lazaro Galdiano museum and in the art market like one formerly with Guilliaume Convert in France and two offered for sale at a Koller auction (see above) and an Alcala Subastas sale in 2013.

[11] Hampel auction, 17 May 2003, lot 147. The pax features an arched top and formerly had a handle. It appears to use the entire impression of a pax as its model for the relief.

[12] With thanks to Neil Goodman for bringing this to my attention (email communication, 2014).

[13] Present author’s database.

Leave a comment