by Michael Riddick

Preview / download PDF in High Resolution

Preview Italian version at Antiqua Nuova Serie

PART 5 of a SERIES OF FIVE PLAQUETTE STUDIES CONCERNING MODERNO AND HIS SCHOOL

Galeazzo Mondella, called Moderno, was the most prolific producer of small bronze reliefs of the Renaissance. While some of his productions were evidently conceived as independent works-of-art others were likely intended to be grouped in a series. Further examples ostensibly sought to preserve creations conceived by him originally in more precious materials.

Throughout the course of scholarship various bronze plaquettes attributed to Moderno have instead been reallocated to followers or presumed anonymous workshop assistants. These artists are today identified by pseudonyms like the Master of the Herculean Labors, the Coriolanus Master, Master of the Orpheus and Arion Roundels, Master of the Corn-Ear Clouds, the Lucretia Master, et al.

While many of these pseudonyms have been applied only in the last few decades, the proposed identity of these artists or their possible reassessment back to Moderno has been little explored due to an absence of information or further critique. However, certain observations may yield reasonable suggestions concerning their context or authorship, particularly as regards the work of Matteo del Nassaro, a gem-engraver whom Giorgio Vasari noted had been a pupil of Moderno as well as a pupil of Moderno’s Veronese contemporary Niccoló Avanzi.

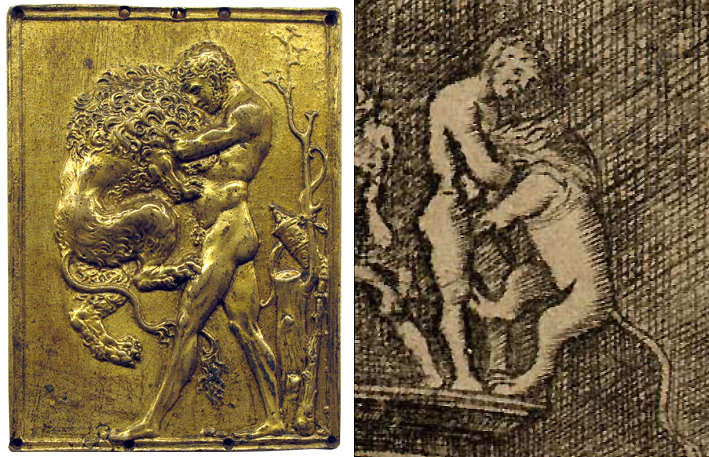

Fig. 1 – Bronze plaquette of a Battle Scene attributed to Moderno, b. 1504 (left; Sandro Ubertazzi collection); obverse of a bronze medal depicting the Battle of Cannae, after Moderno, ca. 1506-07 (right; National Gallery of Art, DC, inv. 1957.14.273.a)

The authorship of a medal memorializing the Battle of Cannae (fig. 1, right) has been debated, with scholars sometimes attributing it to two different artists. While the battle scene on the obverse has traditionally been credited to Galeazzo Mondella, called Moderno, or his workshop, it has also been attributed for the past century to an anonymous artist within Moderno’s circle, identified as the Coriolanus Master. This attribution stems from the fact that the same battle scene appears on a series of plaquettes depicting scenes from the story of Coriolanus, collectively preserved on an inkstand at the Victoria & Albert Museum (cover and fig. 2), and alternatively titled Coriolanus Fighting Under the Walls of Rome. However, as the present author and others have argued, the original relief is properly attributed to Moderno.1 The medal itself is not Moderno’s original invention, but rather an adaptation of his model by another artist, who added a unique inscription and verso. A Battle of Cannae medal adorns the hilt of a sword once owned by Gonzalo de Córdoba, providing a terminus ante quem of 1504-15 for Moderno’s original design, and likely predating 1504 by several years.2 Evidence suggests Moderno’s model was initially conceived in a circular format (fig. 1, left), exhibiting a more complete scene compared to the rectangular version on the Coriolanus inkstand, with figures truncated at its margins.

Fig. 2 – Gilt and silvered bronze inkwell attributed to the Coriolanus Master, ca. 1500, Italy (Victoria & Albert Museum, inv. M.167-1921; photos thanks to Antonia Boström and Freya)

The association of Moderno’s Battle Scene design, featured along with a series of three additional small relief scenes portraying the story of Coriolanus on the V&A inkstand, have entailed their loose association with Moderno. Èmile Molinier first compared these reliefs with the plaquettes produced by the artist signing IO.F.F.,3 mistakenly believed at that time to be the gem engraver Giovanni delle Corniole. Wilhelm von Bode attributed them to Moderno4 while Eric Maclagan5 and Ernst Bange6 opted for an association with an unidentified artist within Moderno’s immediate environment. Seymour de’ Ricci followed this assessment and dubbed the artist his conventionally accepted epithet: the Master of Coriolanus.7 To this suite of Coriolanus themed plaquettes, several others have been added on account of their format, scale, and general style.

The disassociation of these reliefs from Moderno are due to certain qualities that distinguish them from Moderno’s more popularly known works. They are unique in their simplified form and were judged ‘banal’ by Doug Lewis8 while Francesco Rossi described them as ‘dry in their modeling and less compositionally elegant.’9 In the present author’s opinion, they are reminiscent of Girolamo Mocetto’s graphic style, emblematic of a particular austerity and naivety steeped in 15th century modalities. Mocetto’s preference for repeated physiognomic characteristics and his penchant for isometrically aligned heads and figures10 is echoed in the suite of reliefs attributed to the Coriolanus Master (figs. 3 and 17, left).

Fig. 3 – Painted fresco fragment depicting the Continence of Scipio, attributed to Girolamo Mocetto, ca. 1515 (Museo Castelvecchio, Verona)

Mocetto and Moderno may have been aware of one another. They were both close in age and Mocetto may have been apprenticed in Mantua11 while Moderno is presumed active there during the early 1490s.12 Mocetto is also believed to have been active in Verona and Vicenza but probably spent most of his time in Venice near his original home in Murano. The two artists may have intersected in Venice during certain periods. At minimum, Mocetto may have been be aware of Moderno’s inventions, as observed in his possible quotation of Moderno’s Standing Hercules and the Nemean Lion along the upper right margin of a print representing an antique sacrifice (fig. 4).13

Fig. 4 – Gilt bronze plaquette of Standing Hercules and the Nemean Lion by Moderno (left; Museo Nazionale del Bargello, inv. 427); detail of a print of an Antique Sacrifice by Girolamo Mocetto, ca. 1510-30 (right; British Museum, inv. 1845,0825.593)

Apart from his incumbency as head of the goldsmith’s guild in Verona from 1506-07,14 Moderno appears to have spent a considerable amount of time in Venice during the first decade of the 16th century emphasized by commissions he received from Venetian clients during this period. This is indicated by inscriptions featured on casts of his small Madonna and Child with Two Standing Angels reliefs datable to this period as well as his masterpiece group of the Flagellation of Christ and Sacra Conversazione for the Venetian Cardinal Domenico Grimani and the elaborate sword hilt he probably executed for the Venetian commander Giorgio Cornaro.15 Moderno’s presence in Venice is also attested by a contemporary painted enamel Venetian bowl reproducing a derivative of his Battle Scene design also known by a remarkable shell cameo of the same subject formerly in the Orléans collection that is possibly by Moderno or his pupil Matteo del Nassaro.16 Moderno’s models were circulated in Venice while he was still alive, as attested in a document from 1522 citing a Venetian goldsmith in possession of a ‘Saint George on horseback with a dragon, in the form of a wax model by the hand of Moderno,’ which was to be used in the production of a diamond brooch.17

It is worth noting around 1495-1510, Moderno’s Veronese peer, Michele de Verona, treated the subject of Coriolanus’ family persuading him to spare Rome for a painted cassone.18 However, Michele’s compositional treatment has little in common with the same subject presented on the Coriolanus plaquette of the same scene (fig. 2, right). Nonetheless, the vignette style and subject material of cassoni seem directly related to the plaquettes that comprise the V&A inkwell and those other related plaquettes currently assigned to the Coriolanus Master.

Moderno’s awareness of cassoni, of which Verona was a center of production, is suggested in his Entombment plaquette of the late 1490s in which the classicized tomb of Christ features a relief program that Lewis notes are inspired by an awareness of cassone reliefs depicting the abduction and return of Persephone.19 Moderno reinvents this theme in a Christianized context through the very small, but articulate, small relief portrayal of the legend of St. Helen (figs. 5 and 7, left).

Fig. 5 – Detail of the lower register of a plaquette of the Entombment of Christ by Moderno (National Gallery of Art, DC, inv. 1957.14.295)

Not well expounded in literature is the correlation between the plaquettes assigned to the Coriolanus Master and pastiglia caskets20 which are a diminutive corollary to Italy’s cassone production and whose chief production center is believed to have been in Venice and possibly also Ferrara and Mantua during the last two decades of the Quattrocento and into the first half of the Cinquecento.21

Pastiglia boxes, frequently given as wedding or engagement gifts, particularly among Ferrarese and Mantuan brides, are noteworthy. While they may have held natural objects, toiletries, or trinkets, they are also believed to have served as storage for collectibles such as coins, medals, and seals.22 This is of interest because Francisco de Holanda, writing in the mid-16th century, identified Moderno as a maker of lead seals.23 This raises the possibility that Moderno’s production of lead seals may have, directly or indirectly, connected him to those who created the lead moulds needed for pastiglia casket reliefs. Furthermore, if pastiglia caskets were used to store seals, medals, and possibly plaquettes, Moderno would likely have been aware of them. His procurement of metals necessary for the facture of lead seals would also have placed him in the same material market as those involved in producing pastiglia caskets.24

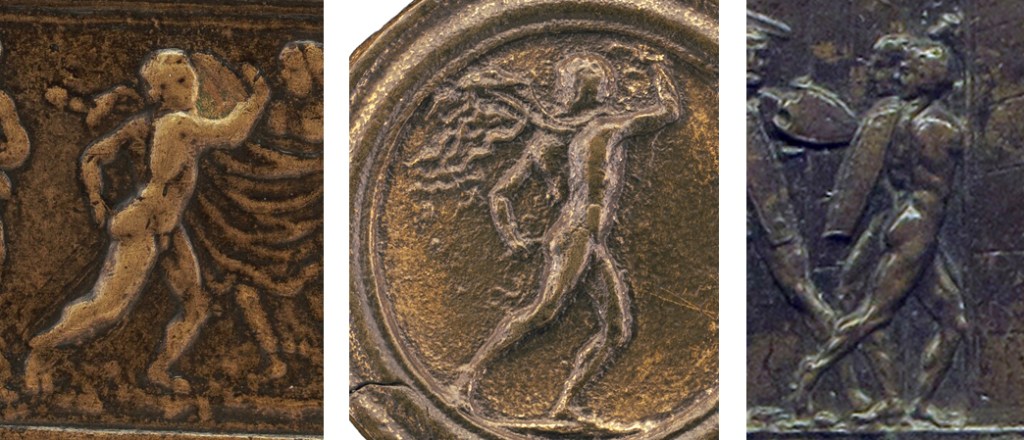

Holanda’s citation of Moderno’s production of lead seals is hardly—if at all—ever discussed in plaquette literature. However, we may note here the closest parallel to the Coriolanus reliefs which are observed in a suite of what Lewis described as Moderno’s ‘miniature tondi.’25 These extremely small compositions, only 3 to 4 cm in diameter (fig. 6), reflect the average size of seals produced during the Renaissance and may represent a preservation in bronze of what would have originally been designs for lead seals produced by Moderno.

Fig. 6 – From top-left to bottom-right: small bronze plaquettes by Moderno, ca. 1495-1510, depicting Marcus Curtius (Victoria & Albert Museum, inv. A.450-1910); A Nude Man (National Gallery of Art, DC [NGA], inv. 1957.14.342); Running Hercules (NGA, inv. 1996.82.2); Vulcan, Victory and Cupid (NGA, inv. 1957.14.311), and David and Goliath (NGA, inv. 1996.82.1)

Lewis dates these seals around the first years of the 16th century and we might accept they reflect his activity in Venice during this period. Venice was a city prolific in the production of seals in addition to Rome, Milan, Florence, and Ferrara.26 Moderno’s seal depicting a Running Hercules (figs. 6, top-right and 7, center) hearkens back to his cassone-inspired relief program on the facade of his Entombment relief and borrows a similarly posed small figure for his Running Hercules (fig. 7, left). Notably, the same pose is reprised on the soldier entering a gate on an Unidentified Military Scene ascribed to the Coriolanus Master (figs. 7, right and 15, right), matching precisely in scale that of the Running Hercules and suggesting both may have derived from a small master model in Moderno’s workshop. The manipulation of this model in wax echoes the same manipulation of models observed in the treatment and application of pastiglia reliefs where slight modifications are introduced to a model according to the subject or theme of a relief.

Fig. 7 – Detail of the lower register of a plaquette of the Entombment of Christ by Moderno (left; National Gallery of Art, DC, inv. 1957.14.295); detail of a plaquette of Running Hercules by Moderno (center; National Gallery of Art, DC, inv. 1996.82.2); detail of a plaquette depicting an Unidentified Military Scene or Attack on a Gate, possibly by Moderno and/or the Coriolanus Master (right; Museo Nazionale del Bargello, inv. 179B)

Worthy of discussion is a two-sided plaquette: a peculiar medal featuring Moderno’s extremely high-relief bust of Faustina on one side (fig. 8, left) and a low-relief Senatorial Triumph composition on the other. The unusual sculptural feature of Faustina preserves only a portion of what was originally a larger sculpted work by Moderno, known by a single cast at the British Museum which Jeremy Warren identified in 2009 (fig. 8, center).27 The original may have been sculpted in hardstone, possibly incorporated as part of a seal handle. Although a superficial observation, it is interesting that the medallic version of Moderno’s Faustina is reproduced in white lead paste on the lid of two pastiglia boxes attributed to the Workshop of the Roman Triumphs (fig. 8, right).28

Fig. 8 – A bronze high relief-plaquette of Diva Faustina by Moderno (left; National Gallery of Art, DC. inv. 1942.9.175.a); a bronze bust of Faustina by Moderno (center; British Museum, inv. PE 1974,1212.4); a white lead pastiglia relief of Faustina, after Moderno, on a pastiglia box attributed to the Workshop of the Roman Triumphs (right; British Museum, inv. 1884,1110.1)

As earlier noted, the subject matter of the reliefs associated with the Coriolanus Master—portraying themes of ancient Roman legends—directly relate to those same moralizing themes found on cassoni and their diminutive variant in the tradition of pastiglia casket production whose centers of activity were immediately in the orbit of Moderno. The otherwise unusual negative space comprising the upper register of the Coriolanus relief compositions directly relate to the same negative space otherwise filled with gilded decorative punch worked grounds observed on pastiglia caskets (fig. 9).29 This same concept is almost implied in the V&A inkwell whose figural scenes are gilded while their open grounds are entirely silvered, sans losses due to age (fig. 2).

Fig. 9 – A pastiglia casket with white lead paste reliefs on a gilded ground, attributed to the Workshop of the Main Berlin Casket (Victoria & Albert Museum, inv. W.23-1953)

While it tempts to suggest the Coriolanus reliefs preserve what could have originally been intended as lead models used to produce pastiglia reliefs, they do not appear on any known survivals of pastiglia caskets although Moderno’s Battle Scene was used on three known pastiglia caskets attributed to the workshop of Moral and Love Themes.30 The feature of two of Moderno’s designs on pastiglia caskets could suggest his direct or indirect association with such workshops. It is probably not without coincidence that Patrick de Winter has likewise noted the probable influence of Mocetto on the artists responsible for producing the lead moulds employed in pastiglia relief production.31 The formal relationship between Mocetto’s works and the reliefs comprising the Coriolanus inkstand—sans Moderno’s Battle Scene—would seem to suggest the inventor of the Coriolanus reliefs was a pupil or amateur, presumably aware or influenced by Mocetto, and active alongside Moderno during his occasional or extended stays in Venice. The Coriolanus inkwell may represent an original context for how the Coriolanus Master’s attributed reliefs may have once been used. They appear to be a precious metal variant of pastiglia boxes, borrowing their general format, inclusive of decorative pillars used to partition their scenes.

Fig. 10 – Reverse of a bronze medal of Agostino Mazzanti, ca. 1485, by Moderno (left; Castello Sforzesco, inv. 0.9.14); bronze plaquette of a Roman Triumph, here attributed to Moderno, ca. 1500 (center; National Gallery of Art, DC, inv. 1957.14.269); bronze plaquette of a Coriolanus Leaving Rome, here attributed to the Coriolanus Master, after a model by Moderno (right; Berlin State Museums, inv. 1108)

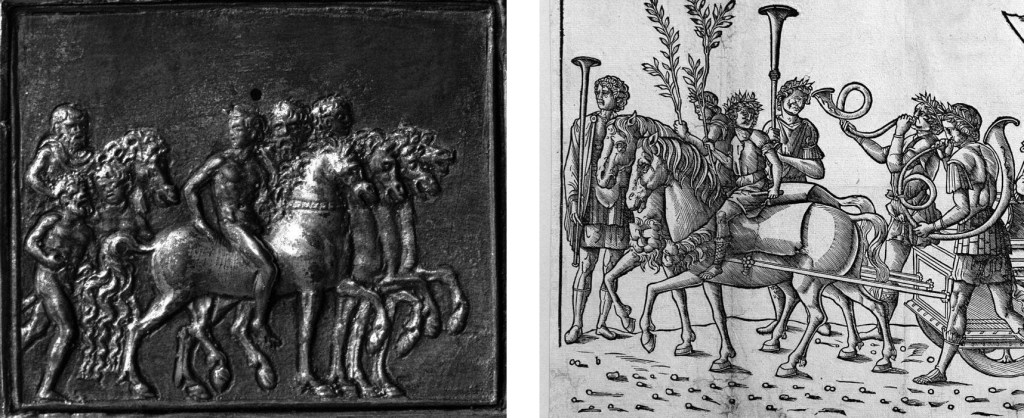

It is already noted the maker of the Coriolanus inkwell appropriated Moderno’s Battle Scene relief, and an additional relief, probably due originally to Moderno, is likewise edited for probable incorporation with the Coriolanus theme. A relief identified as representing a Roman Triumph (fig. 10, center and fig. 12, right)—currently associated with the Coriolanus Master—shares its stimulus in Moderno’s reverse of a medal of Agostino Mazzanti, also featuring a Roman Triumph (fig. 10, left).32 This updated plaquette variation on the theme—here suggested as Moderno’s workmanship on account of it stylistic affinity with his facial types, its fluttering draperies and its relationship with the Mazzanti medal reverse—borrows from that medal’s Triumph composition with regard to the chariot’s ovular wheel and its obfuscation by the tail of the horse in the foreground. In Moderno’s presumably successive treatment of a triumph subject he redacts the densely packed composition for a moderate portrayal of a Roman general brandishing laurel branches from his chariot, now drawn by four horses whose effigy is probably inspired by a northern view of the classical bronze horses originally preserved above the porch of St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice (fig. 11).33

Fig. 11 – Photo of the bronze horses of San Marco, Venice by William Henry Goodyear, ca. 1900 (Brooklyn Museum)

An immediate cognate to this Triumph scene—in respect to figural scale, style, and subject—is that of an Allegory of Victory also associated with the Coriolanus Master, but here judged stylistically still within the parameters of an attribution to Moderno (fig. 12, left). This scarce relief is known by only two examples preserved at the National Gallery of Art, DC, 34 and Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte in Naples.35

Fig. 12 – Bronze plaquette of an Allegory of Victory, here attributed to Moderno, ca. l500 (left; National Gallery of Art, DC, inv. 1957.14.270); bronze plaquette of a Roman Triumph, here attributed to Moderno, ca. late 1500 (right; National Gallery of Art, DC, inv. 1957.14.269)

While most plaquette catalogers have defaulted to assigning these reliefs to subjects pertaining to Coriolanus, we ought to instead consider that they may alternatively preserve a variety of reliefs Moderno originally conceived for bronze desktop objects. The inkwell which survives at the Victoria & Albert Museum appears to be a memory of the utilitarian luxury objects Moderno may have produced for his patrons of this kind. The scenes of a Roman Triumph and Allegory of Victory (fig. 12) may thus belong to what could have been an object specific to a theme portraying Roman triumphs. It may have included additional reliefs of alike manner and subject that simply do not survive or were never copied or reproduced with any degree of seriality. The rarity of the Allegory of Victory is itself a testament to the scarcity of such survivals and we may note also a relief to be discussed, known by a singular example in the collection of Sandro Ubertazzi, which is likewise emphatic of this observation.

The cognate Triumph and Allegory of Victory may have been conceived before the various other small reliefs that assume this format in and around Moderno’s workshop activity. The Triumph’s affinity with Moderno’s medal reverse for Mazzanti, presumably made during the late 1480s, may situate it also during this period, and could correlate to Moderno’s presumed presence and activity in Mantua during this period and probably exposed to the magisterial series of the Triumphs of Caesar being executed by Andrea Mantegna at that time. A reasonable recipient for such an object incorporating these reliefs could have been the condottiero Francesco II Gonzaga, Marquis of Mantua, whom Lewis likewise presumes was one of Moderno’s patrons.36 That Moderno took an interest in producing small bronze utilitarian objects is attested by the survival of the equally rare pear-shaped plaquettes depicting the Judgment of Solomon and Justice, Prudence, and Fortitude, both intended as lamp lids that would have been fitted to a preconfigured base.37 Moderno’s treatment of the subject of Solomon’s judgment is also almost certainly due to Mantegna’s popularization of this moral theme in Mantuan art from the last years of the 15th century38 and could suggest Moderno began producing utilitarian objects of this kind in Mantua during the late 1490s.

A slightly smaller relief, approximately half a centimeter shorter than the Coriolanus reliefs—also reflective of a military triumph—is that depicting a Roman General Crowned Between Minerva and Victory. This relief is likewise scarce with only two examples known from a private collection (fig. 13, left) and another in the Berlin State Museums.39 Its border and scale suggest it too may have once served as an accoutrement to a desktop object. A drawing of the subject, attributed to Cesare da Sesto while in Rome, ca. 1505-12 (fig. 13, right),40 may either copy a sketch originally conceived by Moderno, or could be the design Moderno based his composition upon.41

Fig. 13 – Bronze plaquette of a Roman General Crowned between Minerva and Victory by Moderno (left; private collection); pen and brown ink drawing of a Roman General Crowned between Minerva and Victory by Cesare da Sesto, 1508-ca. 1510 (right; Kupferstichkabinett, Staatliche Museen, Berlin, inv. KdZ 5199)

The Triumph plaquette appears to later serve as the basis for the relief adapted to portray Coriolanus Leaving Rome42 as featured on the V&A inkstand (fig. 2, center [left panel]). This new version of the relief excises the chariot rider to create a horseman while the tail of the foreground’s horse is used to cover-up where the wheel of the chariot had been excised. The most impressive addition to the scene is the central rider with his head turned backwards. This motif must have been known in Venice by early 1503 when the artist, Benedetto Bordone, sketched one of twelve Roman triumphs for woodblocks—to be executed by the woodcutter Jacobus Argentoratensis—and published as a series of prints depicting the Triumphs of Caesar in 1504 (fig. 14).43 If not derived from an antique prototype, it is to be wondered if Bordone referenced a circulated version of this plaquette for his design or if the edited plaquette took inspiration from Bordone’s prints during or after 1504. The latter notion is more likely considering the influence this series of prints had among various workshops specializing in decorative arts, including pastiglia productions as observed in caskets produced by the Workshop of the Roman Triumphs.44 The success of the edited plaquette relief is preserved in the more numerous casts which survive, found in its standard rectangular form but also in two differently sized circular variants, the smaller of which may have been intended as a seal matrix. The modification of an extant relief in Moderno’s workshop is an exemplar for the reinterpretation of an existing model to fit into the context of a newly conceived antique theme: in this case, representing a scene from the life of Coriolanus. This modification to Moderno’s design seems more likely due to a different hand and possibly a pupil or assistant active alongside Moderno while in Venice around 1505.

Fig. 14 – Gilded and silvered bronze plaquette of Coriolanus Leaving Rome, after Moderno, from an inkwell attributed to the Coriolanus Master, ca. 1500, Italy (left; Victoria & Albert Museum, inv. M.167-1921); detail of a woodcut print of a Roman Triumph, after Benedetto Bordone, 1504 (right; Kupferstichkabinett, Staatliche Museen, Berlin, inv. 346)

That the various reliefs assigned to the Coriolanus Master may relate to subjects other than Coriolanus is suggested by Ulrich Middeldorf’s skepticism of the identification of the aforenoted plaquette as representing Coriolanus Leaving Rome.45

Two reliefs superficially described as an Unidentified Military Scene and an Unidentified Naval Scene are noted by Pope-Hennessey as being related, as they feature the same group of protagonists.46 The former is often superficially identified as an Attack on a Port or Gate (fig. 15, right) and the latter has been suggested to represent Aeneas Crossing the Styx (fig. 15, left).47 This pair probably formed another themed suite of reliefs intended for a single object, possibly centered around Virgilian or Homeric subjects, as originally proposed by Wilhelm von Bode in assigning the naval scene to a context belonging to the story of Aeneas.

Fig. 15 – A suite of bronze plaquettes possibly by Moderno and/or the Coriolanus Master of an Unidentified Naval Scene or Agamemnon’s departure for Troy (?) (left; Museo Civico Belluno); a scene of Agamemnon Demanding Tribute from Troy (?) (center; collection of Sandro Ubertazzi); and an Unidentified Military Scene or Agamemnon Sacking Troy (?) (right; Museo Nazionale del Bargello, inv. 179B)

To this suite of scenes may be added a previously unpublished singly known relief from the Ubertazzi collection which features the same protagonists and other figures (fig. 15, center).48 One of the chief characters points toward an entrance amid the huddling group. The scenes remain enigmatic and none appear on the Coriolanus inkstand. However, they might possibly represent a series centered on Agamemnon and his sack of Troy with the Naval Scene representing Agamemnon’s departure for Troy, the newly published scene perhaps representing the demand or collection of a tribute from Troy,49 and the Military Scene representing Agamemnon’s subsequent sack of Troy.

Fig. 16 – Detail of a bronze plaquette possibly by Moderno and/or the Coriolanus Master of an Unidentified Naval Scene or Agamemnon’s departure for Troy (?) (left; Museo Civico Belluno); detail of a bronze plaquette of Hercules and the Oxen of Geryon by Moderno (center-left; National Gallery of Art, DC, inv. 1957.14.326); detail of a bronze plaquette of Agamemnon Demanding Tribute from Troy (?) (center, right; collection of Sandro Ubertazzi); detail of a bronze plaquette of the Resurrection of Christ by Moderno (right; National Gallery of Art, DC, inv. 1957.14.299)

The masterful use of anatomy on this latter suite of plaquettes makes it tempting to assign them to Moderno himself rather than the hand of an assistant, but a final judgment remains challenging. On these reliefs the author reintroduces characteristics from previous works by Moderno. For example, the figure central to the Naval Scene borrows Moderno’s earlier figure of Hercules from his Hercules and the Oxen of Geryon relief of around 1487 (fig. 16, left). The shield-bearing protagonist at the right of the Ubertazzi plaquette echoes the figural form and stance of the standing Roman guard on Moderno’s Resurrection and Crucifixion reliefs of the late 1480s (fig. 16, right) while the soldier entering the gate on the Military Scene echoes once again his small-scale Running Hercules seal motif (fig. 7). On this latter relief, the author also invokes a primary character from Antico’s medal of Divia Iulia,50 and borrowing its chief protagonist for the warrior charging into the gate (fig. 17, second from left). The motif derives from an antique statue that was preserved in the Garden Hall of the Medici Palazzo Madama as observed in an early 16th century sketch drawn by Maarten van Heemsskerck, ca. 1532-36 (fig. 17, right) and Mocetto also references this motif in his panel painting portraying the Massacre of the Innocents (fig. 17, left).

Fig. 17 – From left-to-right: detail of the Massacre of the Innocents, oil on panel by Girolamo Mocetto, ca. 1500-25 (National Gallery, London, inv. NG1240); detail of a bronze plaquette of an Unidentified Military Scene or Agamemnon Sacking Troy (?) by Moderno and/or the Coriolanus Master (Museo Nazionale del Bargello, inv. 179B); detail of a medal reverse with a Battle Scene by Antico, ca. 1500-02 (National Gallery of Art, DC, inv. 1957.14.666.b); detail of a pen and grey ink sketch of the Garden Hall of the Palazzo Medici-Madama with Antique Sculptures by Maarten van Heemskerck, ca. 1532-37 (Kupferstichkabinett, Staatliche Museen, Berlin, inv. 79 D a, fol. 48r)

While it is earlier explained that the maker of the Coriolanus inkwell adapts two of Moderno’s extant works to create scenes from the life of Coriolanus, there are two additional reliefs added to the series that portray scenes of Coriolanus and the Women of Rome and the Judgment or Banishment of Coriolanus (fig. 18).51 These two reliefs lack the visual strength and aptitude of Moderno’s work. Particularly unsatisfactory is the awkward scale of the Roman magistrate on the Banishment plaquette and the naïve architectural execution of his plinth52 as well as the equally amateur contubernium portrayed on the Women of Rome relief. Their execution opposes the rather superior execution of architectural forms found in Moderno’s oeuvre, already evident in his earliest large plaquette of St. Sebastian, showcasing his talent in portraying classicized architecture in low-relief.

Fig. 18 – Bronze plaquette of the Banishment of Coriolanus by the Coriolanus Master (Matteo del Nassaro?), ca. 1500-12 (left; National Gallery of Art, DC, inv. 1957.14.271); bronze plaquette of Coriolanus and the Women of Rome by the Coriolanus Master (Matteo del Nassaro?), ca. 1500-12 (right; National Gallery of Art, DC, inv. 1957.14.267)

Contrary to the aforenoted scenario is a larger plaquette where Moderno’s talents at architectural rendering takes precedence while the small-scale figures at the base of the composition appear to be the added work of a lesser hand. A plaquette thought to portray Samson Destroying the Temple is first discussed by Bode in 1904 who considered it an anonymous Italian work of the mid-16th century and tentatively described it as a scene of ‘Samson’s rage’ (fig. 19).53 Bange followed Bode’s assessment of a mid-16th century origin although alternatively considered it a German, Swabian or Augsburg invention.54 A century later, Philippe Malgouyres considered it North Italian and of the early 16th century.55 However, the most thorough examination of this plaquette comes from Trinity Fine Art’s assessment which considered it a work of the early 16th century and belonging to a close follower of Moderno, though lacking his ‘power and lucidity,’ and rightly comparing its figures with the plaquettes ascribed to the Coriolanus Master.56

Fig. 19 – Bronze plaquette of the Samson Destroying the Temple of the Philistines here attributed to Moderno and the Coriolanus Master (Matteo del Nassaro?), ca. 1506-12 (Museo Correr, Venice, inv. Cl. XI n. 0074)

Lewis and Rossi have previously noted how Moderno’s series of four Herculean labors, executed ca. 1487, although set in Rome, relied upon a detailed observation of Veronese architectural antiquities as sources for their visual settings.57 This practice attests to Moderno’s interest in architecture and the ruins of the Samson relief appear to emulate the Roman theater of Marcellus which Moderno may have seen in Rome or accessed through sketches. There is a good possibility Moderno himself prepared the background for the Samson plaquette, given its more refined execution compared to the less skillful figural forms in the relief’s lower register. The feature of ruinous architecture follows other works executed by Moderno and its double-moulded rim-fillet with a single-moulded base rim is a workshop template employed in many of his creations. There are also redacted features in the architecture that recall Moderno’s interpretations like the architectural setting portrayed on his Flagellation relief, for example.

The Coriolanus Master, who presumably had his hand in the addition of the figures along the base of the relief, appears to likewise reference Roman antiquities, such as the figure within the right portico which borrows its pose from a classical figure of Apollo Lykeios, being one of the antiquities kept in Jacopo Galli’s sculpture garden. The figure is distinguished by the projecting right hip and the proper right arm which reaches into the subject’s hair. The figure beneath the central portico echoes the Laocoon sculpture group unearthed in Rome in 1506, providing a terminus post quem for this plaquette, while that same motif is adopted also by Moderno for his representation of Christ on his earlier noted Flagellation relief.

Fig. 20 – Detail of a bronze plaquette of the Death of Lucretia attributed to Moderno (National Gallery of Art, DC, inv. 1957.14.338); detail of a bronze plaquette of Orpheus Losing Eurydice, here attributed to Matteo del Nassaro in the workshop of Moderno (National Gallery of Art, DC, inv. 1957.14.332)

The information presented here aims to differentiate a majority of the plaquettes assigned to the Coriolanus Master and return them mostly to Moderno’s authorship, citing his interest in very small relief work and his probable, albeit presumably limited, production of desktop objects. The earliest reliefs of this type may relate to the suite of small Roman Triumph plaquettes which appear to most closely follow Moderno’s style and appear related to his tenure in Mantua. The suite of reliefs possibly portraying Agamemnon may also be Moderno’s workmanship, and if not, then possibly that of a close collaborator and presumably executed in Venice. The suite associated with Coriolanus appear to depend on Moderno’s models and influence and are thus by an amateur hand or that of a pupil. It is not without possibility that the Coriolanus Master could be the earliest works of Moderno’s only known pupil, Nassaro, who may have been trained by Moderno ca. 1508-12. Giorgio Vasari’s note that Moderno instructed Nassaro in gem-engraving58 would relate to the small-scale production observed in the Coriolanus reliefs. As previously proposed by the present author, Nassaro uses Moderno’s border templates for his production of a series of roundels portraying Arion and Orpheus59 and a similar practice is observed in the Coriolanus Master’s use of Moderno’s templates in the realization of the Coriolanus reliefs. Nassaro even seems to borrow a to-scale impression of Lucretia from Moderno’s roundel depicting the Death of Lucretia for his feature of Eurydice in his roundel of Orpheus Losing Eurydice (fig. 20). If we consider the order in which Vasari notes Nassaro’s instructors, beginning with Moderno and following with Niccoló Avanzi,60 we could predict Nassaro was under Moderno’s influence sometime before 1512 when he is cited in Rome that year alongside Avanzi,61 but following his earlier tutelage in music in Mantua after 1499.62 This would place Nassaro’s training under Moderno sometime during the first decade of the 16th century, a period in which Moderno not only served a two year incumbency as head of the Verona goldsmiths guild, but was also probably abundantly active in Venice and presumably alongside an assistant or pupil.

Endnotes:

1 Douglas Lewis (1989): The Plaquettes of ‘Moderno’ and His Followers in Studies in The History of Art, vol. 22, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC., pp. 105-41; Francesco Rossi (2011): La Collezione Mario Scaglia – Placchette, Vols. I-III. Lubrina Editore, Bergamo, pp. 218-19, no. V.27; and Michael Riddick (2024a): The Battle of Cannae Medal – A German-Italian Crossover? Renbronze.com (accessed April 2025).

2 M. Riddick (2024a), Ibid.

3 Èmile Molinier (1886): Les Bronzes de la Renaissance. Les plaquettes. Paris, nos. 140 and 634.

4 Wilhelm von Bode (1904): Beschreibung der Bildwerke der Christlichen Epochen: Die Italienischen Bronzen. Berlin, Germany: Konigliche Museen zu Berlin, no. 786.

5 Erik Maclagan (1924): Catalogue of Italian Plaquettes. Victoria and Albert Museum, London, p. 41.

6 Ernst Bange thought the artist may have been active in Padua as an imitator of Moderno. Ernst Bange (1922): Die Italienischen Bronzen der Renaissance und des Barock. Zweiter Teil: Reliefs und Plaketten. Vereinigung Wissenschaftlicher Verleger Walter de Gruyter & Co., Berlin and Leipzig, Germany, nos. 506-11, pp. 69-70.

7 Seymour de’ Ricci agreed with Bange’s assessment of a Paduan origin by an artist under the immediate influence of Moderno, dubbing him the “Coriolanus Master.” Seymour de’ Ricci (1931): The Gustave Dreyfus Collection. Reliefs and Plaquettes. Oxford, no. 148, p. 118.

8 Douglas Lewis (1987): The Medallic Oeuvre of “Moderno”: His Development at Mantua in the Circle of “Antico” in The History of Art, vol. 21, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, pp. 77-97, see p. 83.

9 Francesco Rossi (1974): Placchette. Sec. XV-XIX. Vicenza, p. 118.

10 Giorgio Tagliaferro (2011): Girolamo Mocetto in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, LXXV, pp.162-66.

11 David Landau (2016): Printmaking in Venice at the time of Manutius in Aldo Manuzio: Renaissance in Venice. Venice, pp.111–12 and G. Tagliaferro (2011): Ibid., p.164. See also Serena Romano (1985): Rittrato di Fanciullo di Girolamo Mocetto. Modena, Galleria Estense.

12 D. Lewis (1987): op. cit. (note 8) and D. Lewis (1989): op. cit. (note 1).

13 Mocetto’s use of this motif may equally derive from a very similar bronze sculpture in-the-round, attributed to Vittore Gambello in Venice, ca. 1500, an example of which is preserved in the Cleveland Museum of Art. See William Wixom (1975): Renaissance Bronzes from Ohio Collections. Cleveland Museum of Art, no. 110. See also Cleveland Museum of Art, inv. 1975.111.

14 Luciano Rognini (1973-74): Galeazzo e Girolamo Mondella – artisti del Rinascimento Veronese in Atti e Memorie della Accademia di Agricoltura, Scienze e Lettere di Verona, vol. VI, XXV, pp. 95-119.

15 D. Lewis (1989): op. cit. (note 1).

16 For the cameo and Venetian bowl see figs. 17 and 18 in Michael Riddick (2019): Glyptics, Italian Plaquettes in France, and their Reproduction in Enamel. Renbronze.com (accessed March 2025).

17 Clifford Brown (1997): The Archival Scholarship of Antonino Bertolotti – A Cautionary Tale in Essays in Honor of Carolyn Kolb, Artibus et Historiae. Vienna-Krakow, p. 68 ff.

18 National Gallery, London, inv. NG1214.

19 D. Lewis (1989): op. cit. (note 1).

20 Patrick de Winter examines the appearance of plaquette reliefs on pastiglia caskets and Marika Leino slightly expands on the subject in: Patrick de Winter (1984): A Little-known Creation of Renaissance Decorative Arts: The White Lead Pastiglia Box in Saggi e Memorie Di Storia Dell’arte, no. 14, pp. 7–131 and Marika Leino (2013): Fashion, Devotion and Contemplation. The Status and Functions of Italian Renaissance Plaquettes. Peter Lang, Bern, Switzerland.

21 P. Winter (1984), ibid., p. 10.

22 Ibid., p. 9.

23 Francisco de Holanda (1548): Da Pintura Antigua. Edited by Joaquim de Vasconcellos (1930), Segunda Edicao da Renascena Portuguesa Porto, p. 302.

24 In addition to the lead moulds used to produce pastiglia reliefs, workshops also employed a white lead paste to produce the reliefs themselves. See P. Winter (1984): op. cit. (note 20).

25 As described by Lewis in D. Lewis (1987): op. cit. (note 8).

26 Ibid., see his endnote 2.

27 Jeremy Warren (2014): Medieval and Renaissance Sculpture in the Ashmolean Museum, Vol. 3: Plaquettes. Ashmolean Museum Publications, UK, no. 327, pp. 870-71. See also British Museum, inv. PE 1974,1212.4.

28 British Museum, inv. 1884,1110.1 and the Palazzo Barberini, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica, inv. 2108.

29 P. Winter (1984): op. cit. (note 20), p. 11.

30 Victoria and Albert Museum, inv. 82-1890; Castello Sforzesco, Milan (Civiche Raccolte d’arte Applicata), inv. 93; and a private collection (Christie’s auction, 24-26 September 1979, lot 5).

31 P. Winter (1984): op. cit. (note 20).

32 Examples of this medal are preserved at the Castello Sforzesco (reproduced here), the Cabinet des Medailles in Paris and the Goethesammlung in Weimar. The reverse of this medal is also later appropriated and used on a medal of Ottavio Farnese from the third quarter of the 16th century. See D. Lewis (1987): op. cit. (note 8), his endnote 16.

33 Francesco Rossi groups this plaquette with those depicting and Unidentified Military Scene and Unidentified Naval Scene, and interestingly suggests they represent scenes from the story of Tarpeia, noting the Triumph plaquette as possibly representing the triumph of Romulus. F. Rossi (2011): op. cit. (note 1), no. III.15, pp. 122-23. However, this Roman Triumph relief does not appear to relate to the non-bearded characters featured in the other two aforenoted plaquettes.

34 National Gallery of Art, DC, inv. 1957.14.270.

35 Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, inv. 10985.

36 D. Lewis (1987): op. cit. (note 8), see p. 77.

37 D. Lewis (1989): op. cit. (note 1), see figs. 39, 40.

38 See for example the grisaille painting of the subject attributed to Andrea Mantegna and his studio at the Louvre, inv. 5068, Recto.

39 Berlin State Museums, inv. 3047.

40 M. Leino (2013): op. cit. (note 20).

41 We may note Giorgio Vasari praised Moderno for his skills as a draughtsman although only two sketches in the Louvre are the only works associated with him in this capacity (invs. 5077, recto and 5078, recto). See also Giorgio Vasari (1568): Lives of the most Eminent Painters Sculptors and Architects. Vol. 06 (of 10), Fra Giocondo to Niccolo Soggi. Translated by Gaston du C. De Vere, 1913. Macmillan and co. ld. & the Medici Society, London, pp. 79-80.

42 Bange describes the relief as the Dispatch of the Five Consuls to Coriolanus. E. Bange (1922): op. cit. (note 6).

43 David Landau and Peter Parshall (1994): The Renaissance Print, 1470-1550. Yale University Press, pp. 150, 300.

44 P. Winter (1984): op. cit. (note 20), pp. 18-19.

45 Middeldorf notes: ‘the interpretation of this scene is doubtful,’ in Ulrich Middeldorf (1944): Medals and Plaquettes from the Sigmund Morgenroth Collection. Chicago, nos. 254-55, p. 36.

46 John Pope-Hennessy (1965): Renaissance Bronzes from the Samuel H. Kress Collection. Reliefs, Plaquettes, Statuettes, utensils and mortars. London, nos. 91 and 92, pp. 30-31.

47 W. Bode (1904): op. cit. (note 4), no. 780, p. 69.

48 As of 2017, Sandro Ubertazzi’s collection no. 71.

49 The composition of this plaquette loosely recalls Masacio’s Tribute Money fresco at the Brancacci Chapel in Florence.

50 Philippe Malgouyres has made an interesting argument that this medal depicts a portrait of Ippolita Maria Sforza. Philippe Malgouyres (2017): L’Antico et l’Art de la Medaille: Le Travestissement Biographique a l’Antique a la Cour de Gianfrancesco Gonzaga in Rivista Italiana di Numismatica e Scienze Affini, vol. CXVIII, pp. 199-220.

51 Francesco Rossi makes the noteworthy observation that the figure of an enthroned Roman magistrate may have been derived from the figure of Herod Agrippa in the fresco of the Judgment of San Giacomo by Andrea Mantegna at the Cappella Ovetari in Padua. F. Rossi (2011): op. cit. (note 1), p. 119.

52 It is unusual that the common acronym, SPQR, frequently engraved or integrally cast on the independent plaquette casts of this relief does not feature on the inkstand at the Victoria & Albert Museum. Perhaps it was presumed the gilded surface would obfuscate such an inscription or perhaps it was deemed unnecessary due to the references along its inscribed base which already associate the scenes to the story of Coriolanus. See figure 2.

53 W. Bode (1904): op. cit. (note 4), p. 122, no. 1279.

54 E. Bange (1922): op. cit. (note 6), no. 2821, p. 101.

55 Philippe Malgouyres (2020): From Filarete to Riccio. Italian bronzes of the Renaissance (1430-1550). The collection of the Louvre Museum, Paris, Louvre Editions; Mare & Martin, no. 416, p. 426.

56 Trinity Fine Art Ltd. (2008): Works of Art Presented in London Sculpture Week, 13-20, June 2008, no. 7679. This example was acquired by them from the Spink & Son sale, 24 January 2008, lot 88.

57 D. Lewis (1989): op. cit. (note 1); F. Rossi (1974): op. cit. (note 9).

58 G. Vasari (1568): op. cit. (note 41).

59 Michael Riddick (2024b): Proposing Matteo del Nassaro as the Master of the Orpheus and Arion Roundels. Renbronze.com (accessed April 2025).

60 Giorgio Vasari (1568): op. cit. (note 41). See also Henri de la Tour (1893): Matteo dal Nassaro in Revue numismatique, no. 11, p. 542.

61 Alessandro Luzio and Rodolfo Renier (1896): Il lusso di Isabella d’Este in Nuova antologia, no. 64, pp. 323-24.

62 For the dating of Matteo del Nassaro’s training in music see M. Riddick (2024b): op. cit. (note 59) and William Prizer (1978): Marchetto Cara at Mantua: New Documents on the Life and Duties of a Renaissance Court Musician in Musica Disciplina, vol. 32, pp. 87-110.

Leave a comment