by Michael Riddick

Download / Preview High-Resolution PDF

The Origins of the all’Antica Plaquette

The genesis of Renaissance bronze plaquettes is indebted to the revival of glyptic art in Italy, encouraged by the patronage and collecting fervor of popes, cardinals, and Humanist nobles, as well as to the admiration and study of ancient gems by contemporary artists who incorporated them as models in their work.

In particular, the eccentric antiquarian, Cardinal Pietro Barbo—who became Pope Paul II in 1464—was lauded for his passion of antiquity and amassed one of the largest collections of its type during his lifetime. His inventory, begun in 1457, describes his vast collection of ancient coins, cameos, and engraved gems; organizing them into categories of portrait busts, full-length figures, emperors, empresses, and persons of renown.1 It is under his probable patronage that plaquettes—small reliefs produced in bronze—was conceived.

Precious classical gems were esteemed among avid collectors and artists who desired to portray Italy’s ancient golden age in the epoch of the new Renaissance. While most gem collections remained the private property of their owners—shared on special occasion with guests or other erudite collectors—Paul II was rather different in the treatment of his collection, unabashed in sharing with others the prizes he so personally admired while leveraging them to communicate a contemporary image of himself through the lens of a classical ethos.

During the Renaissance, the earliest and most common diffusion of these gems came by way of gesso or wax impressions of them. Gem impressions could be made and delivered with the intent to sell or share examples among collectors. This is attested in several sources, like Filarete’s ownership of a plaster impression of a precious cameo preserved in the basilica of St. Sernin in Toulouse,2 an example of which Paul II must have likewise owned, as he voraciously pursued in vain to purchase the original.3 Lorenzo de’ Medici’s receipt of a plaster cast intaglio of Phaethon,4 owned by Giovanni Ciampolini,5 as well Lorenzo’s request for casts of cameos belonging to Cosimo Sassetti’s collection, are further examples of this practice.6 Wax impressions were also used, such as Luigi da Barberino’s wax impression of a gem on a letter he sent to Nicolò Michelozzi, to offer ‘an impression’ of what it looked like.7

The earliest documented example of a gem impression cast in metal is a lead image of Scylla, reproduced from an antique gem owned by Cyriac of Ancona, of which he gave examples to Teodoro Gaza and Angelo de’ Grassi, the bishop of Ariano Irpino, in 1442.8 It is to be wondered if Paul II, during his earlier years as a Cardinal in service to his uncle, Pope Eugene IV, may have been aware of this practice of Cyriac, as Eugene IV was a great patron of Cyriac during his pontifical tenure. While no documentation has surfaced concerning the reproduction of Paul II’s gems in bronze, there are several points of evidence, discussed in previous scholarship, that encourages this notion. Chief among these are the renovation projects instituted by Paul II at his Palazzo di San Marco residence in Rome (now the Palazzo Venezia), begun while he was still a Cardinal in 1455.9

One of the earliest known portrait medals cast in Rome, presumably made sometime just before 30 August 1464—and the earliest of many to be commissioned and cast for the Cardinal and future Pope—is one profile portrait medal depicting Barbo as a Cardinal with his armorial on the reverse. As noted by George Francis Hill, a subsequent edition of this medal, with an alternative verso, was made portraying the newly planned façade of the Palazzo di San Marco, dated 1464,10 and coinciding with the enlarged building plans for the palace that were drafted upon Barbo’s election to the papacy that year. A slightly later modification to this aforenoted medal’s reverse, bearing the year 1465, and featuring an altogether newly modeled profile portrait of the elected Pope on its obverse, was serially produced in that year (fig. 1) and intended for distribution and internment in the foundation of the new additions being made to the palace, a practice executed by Paul II in true all’antica tradition.11

Fig. 1: Bronze portrait medal of Pope Paul II (obverse), attributed to Cristoforo di Geremia, 1465, with the facade of the Palazzo di San Marco (reverse) (Münzkabinett, Dresden, Germany)

On stylistic grounds, this latter medal is attributed to the Mantuan goldsmith and metal-worker, Cristoforo di Geremia, who was active in Rome under the earlier patronage of the prelate Ludovico Trevisan, another avid collector of gems and antiquities.12 Cristoforo is believed to have entered Paul II’s service not long after the death of Trevisan on 22 March 1465.13

As part of Paul II’s enlargement of the Palazzo di San Marco, begun in 1465, a new roof was added and completed by the year 1467. The roof was made with gilt lead tiles, examples of which incorporated an impression of a medal by Pisanello and another which reproduced the aforenoted portrait medal of 1465, attributed to Cristoforo.14 A vast quantity of these latter medals must have been produced, not only for private distribution by Paul II to his peers, but also for burying in the foundations of the enlarged palace. The medals were coated in wax as a protective seal and inserted in groups of two, three or five into individual dindaroli or terracotta containers (fig. 2), and buried approximately 10 feet apart along its foundation, around doorways and beneath staircases. An archival document from 1466 cites payments for 129 containers,15 thus suggesting a great quantity of medals must have been cast for the purposes of internment alone.

Fig. 2: A collection of 15th century dindaroli discovered at the Palazzo di San Marco (Palazzo Venezia, Rome)

It is due to this prolific production that bronze casts reproducing gems from Paul II’s collection are thought to have emerged from this activity—and as suggested by Luke Syson and Dora Thornton—possibly under the supervision of Cristoforo Geremia.16 This seems possible given Cristoforo’s antiquarian expertise and Paul II’s commission to have Cristoforo restore the historic equestrian monument of Marcus Aurelius in 1466-68.17 However, other bronze founders like Andrea Guacialoti, possibly responsible for Paul II’s medal celebrating his ascension as Pope in 1464, should not be ruled out.18

Cristoforo’s former proximity with Trevisan—a vocal opponent of Paul II19—and his familiarity with that prelate’s possessions—aside from being an antiquaire himself20—must have interested Paul II. It is to be wondered if Cristoforo could have had some role in facilitating or valuing the distribution of antiquities from Trevisan’s estate, perhaps related to Paul II’s almost immediate acquisition of important gems from Trevisan’s collection like the prized Augustan convex carnelian intaglio of Apollo, Marsyas and Olympus,21 often dubbed the ‘Seal of Nero (fig. 3).’22 However, the Pope himself may have simply exercised his newfound power to conveniently acquire such important works from that estate.23

Fig. 3: Carnelian intaglio of Apollo, Marsyas and Olympus, often called the ‘Seal of Nero’ (Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli, inv. 26051)

Plaquette casts of one of Paul II’s gems, and possibly two others, may predate this prolific activity of the casting for the Palazzo di San Marco construction efforts of 1465-67, thought to have been produced in a foundry tentatively dubbed the ‘Officine di San Marco.’24 For example, Paul II’s bronze portrait medal, executed by an unknown hand while still a Cardinal and made sometime before the end of August 1464, is evidence that Paul II already had use of an unidentified bronze founder in service to him. The first plaquette, certain to date probably before September of 1464, is that reproducing Paul II’s white amethyst intaglio portraying Abundance and featuring its original precious mount commissioned by the then Cardinal with his armorial depicted along its lower margin (fig. 4, right). In 1457, the Abundance amethyst was Paul II’s most valuable gem, as recorded in his inventory.25

Fig. 4: Bronze cast after the ‘Felix Gem,’ cast in Rome probably before September 1464 (left; Ashmolean Museum, inv. WA2020.17); bronze cast after an amethyst with an allegorical figure of Abundance with the precious mount of Cardinal Pietro Barbo, probably cast in Rome before September 1464 (right; National Gallery of Art, DC, inv. 1957.14.169)

Another early production could involve bronze plaquette copies of another prized gem: Paul II’s sardonyx cameo of Odysseus and Diomedes with the Palladium, signed by a certain Felix, and later dubbed the ‘Felix Gem.’26 The impression of the gem’s composition is weakly reproduced on these plaquettes and could infer an early experimentation in reproducing the most precious objects from his collection (fig. 4, left).27

Among the surviving casts representing antique gems from Paul II’s collection, the two aforenoted plaquettes are exceedingly rare and approximately half of the known surviving examples of each of them uniquely feature an integrally cast suspension loop, suggesting they may have been cast in proximity of one another and intended to be prized and worn as pendants,28 perhaps allowing the Pope to travel with examples of his favorite objects, or as Francesco Rossi suggests, offered as New Years gifts to his closest confidants and friends,29 like his cousin and fellow antiquaire, Cardinal Marco Barbo, also a resident with him at the Palazzo di San Marco.

That Paul II probably distributed casts of gems to others is inferred by the presence of several plaquettes which appear in relief as spandrels on a colonnade depicted on the interior silver lining of the Shrine of Saint Simeon in Zadar, executed by Tommaso di Martino of Zara, and completed by 30 April 1497 (fig. 5).30 The reliefs are executed with such fidelity to presume the silversmith, Tommaso, was operating with very good contemporary casts of these reliefs, whether in gesso or bronze.

Fig. 5: Details of the gilt silver interior lining of the Shrine of St. Simeon in Zadar by Tommaso di Martino of Zara, 1497, reproducing plaquettes of a Head of Minerva (left) and Julius Caesar (right) (Church of St. Simeon, Zadar, Croatia)

Documents from the 1450s indicate the archbishop of Zadar, Maffeo Vallaresso, was in pursuit of all’antica motifs for a variety of projects he was commissioning in that city. His intent was to provide such resources to local craftsman in the execution of various projects, a tradition established and preserved in the updates made to the Shrine of Saint Simeon by the end of the 15th century. Notably, Vallaresso’s brother, Giacomo, was a Roman member of Paul II’s circle, and Maffeo himself made occasional stays at the Pope’s Palazzo di San Marco, visiting there while the Pope was still a Cardinal and later, in 1466 and 1468.31 Also worth noting is that Paul II was still a Cardinal, when assigned as abbot-commendatore of the Benedictine monastery of St. Krsevana in Zadar in 1447, sending his older brother, Paolo and the cleric, Nicola de Nai of Padua, to fulfill various of those responsibilities on his behalf. The Barbo influence in Dalmatia is further emphasized by Paul II’s other brother’s role of the same kind at the monastery of St. John the Baptist in Trogir beginning in 1468 and had at least four other abbeys under his influence during this period.32 The presence of these plaquettes featured on the shrine of St. Simeon point to a confident origin within Paul II’s sphere and notably involve plaquettes depicting Julius Caesar (fig. 5, right), a Bust of a Classical Youth, Head of Minerva (fig. 5, left), Bust of Diana, and a freehand copy of Apollo, Marsyas and Olympus executed by Cristoforo Geremia, to be discussed.

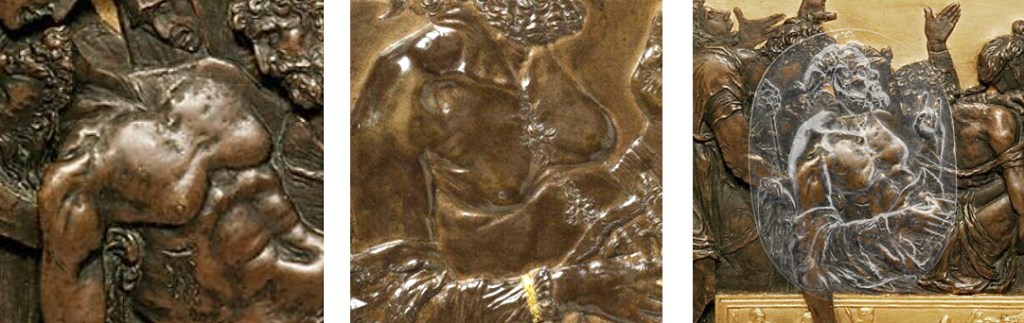

A third plaquette that may have emerged prior to the prolific casting efforts for the Palazzo di San Marco construction projects are those reproducing the Apollo, Marsyas and Olympus gem, or so-called ‘Seal of Nero,’ featuring its integral mount made by Lorenzo Ghiberti in 1428 (fig. 6, left).33 As noted by Douglas Lewis, these casts represent the gem and its setting while it was still in the possession of Trevisan. Their lackluster quality appears to be due to Lewis’ observation that the casts are “pirated from a crudely overlapped (partially doubled) seal impression—presumably on the basis of a carelessly executed wax seal”34 and that the plaquettes utilized this wax impression as a model for their casting. Lewis further suggests that the casts, perhaps made during the 1450s, may be due to Paul II’s ambitions, being unable to directly access the original gem on account of tensions at-that-time with Trevisan, yet desirous of an example of the gem for his own purposes.

Fig. 6: Bronze plaquette of the ‘Seal of Nero,’ probably cast in Rome after a wax seal impression before 1465 (left; Cabinet des Medailles, Bibliothèque Nationale, inv. 442); bronze plaquette after a carnelian of Apollo, Marsyas, and Olympus with later mount, cast probably in 1468 (center; Mario Scaglia collection); gilt bronze medallic reverse of a medal, based upon the ‘Seal of Nero,’ by Cristoforo Geremia, 1468, Rome (right; Palazzo Venezia)

Indeed, upon acquiring the famed carnelian from Trevisan’s estate, Paul II subsequently launched a campaign in celebration of his peace proclamation of 25 April 1468 which employed a multi-faceted use of the gem and its iconography. In close proximity with this event, he appears to have recontextualized the gem by removing its former Florentine-themed setting by Ghiberti and introducing a new band setting relative to his peace proclamation.35 This new setting is reproduced in a very rare variant of plaquette casts of the gem (fig. 6, center).36 On this occasion, Paul II also tasked Cristoforo Geremia with the creation of a portrait medal to memorialize the event.37 In this effort, Cristoforo created a revised portrait of the Pope and a medallic reverse featuring a newly modeled freehand copy of the Apollo, Marsyas and Olympus gem (fig. 6, right).

These events inform us of two noteworthy practices of Paul II: first, that he was possibly inclined to copy in bronze an important object he was unable to obtain; and secondly, that he authorized a bronze contemporary copy of a prized antique gem in his possession.

Giuliano di Scipio

This brings our discussion to a gem-cutter of which there is little known but who was situated in the environment of activity surrounding Paul II, Cristoforo Geremia and a host of other noteworthy patrons, collectors, and artists. Of especial note is his presence at the intersection of Rome and Mantua and his role, whether active or passive, in the realization of one of the masterpieces of Renaissance bronze relief work: the Martelli Mirror.38

On 17 April 1470, and just two years after Paul II’s campaign promoting his peace proclamation, he instituted a papal bull establishing a new pattern for the jubilee cycle. To celebrate he commissioned the gem-engraver, Giuliano di Scipione Amici, to execute a carnelian intaglio portrait commemorating the event (fig. 7). The carnelian is the only known documented work of Giuliano, recognized in 1929 by Ernst Kris,39 and following upon earlier published records of the Papal Treasury discovered by Eugène Müntz.40 The carnelian is inscribed, ANNO PUBLICATIONIS JUBILEI, referring to the jubilee, and thus informing that Giuliano’s carnelian intaglio portrait of the Pope must have been completed between mid-April 1470 and the end of that year. Approximately four months after the Pope’s unexpected death, in 1471, Giuliano petitioned to the Apostolic Chamberlain of the Papal Treasury for payment concerning the carnelian portrait as well as payment for other items he had either gifted or worked-on for the Pope.41

Fig. 7: Carnelian intaglio portrait of Pope Paul II by Giuliano di Scipio, 1470, Rome (Palazzo Pitti, Museo degli Argenti, inv. Gemme no. 323)

Paul II was without hesitation in having bronze casts produced after Giuliano’s contemporary gem (fig. 8).42 Such casts inform us of Paul II’s continued interests in the seriality of bronze as a prestigious medium through which to convey not only his interests in antiquity but also the continuing promulgation of his public image and legacy. The plaquette copies were likely made in conjunction with the jubilee and before the death of the pope on 26 July 1471.43 These bronze casts also reproduce the carnelian’s original setting and this too is quite possibly Giuliano’s invention.

Fig. 8: Bronze plaquette, 1470, after a carnelian intaglio portrait of Pope Paul II by Giuliano di Scipio, Rome (private collection)

It ought to be recognized that gem-engraving frequently belonged to the realm of the goldsmith and that while Giuliano’s expertise may predominantly have involved the working of hardstones, he probably also worked with other precious materials and may have likewise had some involvement, even if only administrative, in the bronze casts that reproduce his masterful carnelian intaglio of the Pope. One detail that may attest to Giuliano’s powers as a goldsmith is the uniquely preserved and rare example of two entirely gold casts of Giuliano’s intaglio which survive in the Vatican Medagliere in Rome and at the Museo Correr in Venice.44

In the sparse art historical discourse available concerning Giuliano he is frequently cited as only a gem-engraver and dealer of antiquities. However, the accounts of his petition to the Apostolic Chamberlain seem to have been somewhat misread in contemporary scholarship. Modern literature suggests that Giuliano had something to do with the dispersal and sale of Paul II’s collection of gems from the Papal Treasury following Paul II’s death and while Giuliano may very well have been appointed such a role from the incumbent Pope Sixtus IV, there is more to be observed in the notes concerning the record of his requests.

On 30 November 1471, during the settlement of debts owed to Giuliano from the Papal Treasury, he described several carved-gems he sought payment for from Paul II’s estate, noting that four of them were already in Cardinal Francesco Gonzaga’s possession and that the carnelian portrait he had made of Paul II was in Domenico di Piero’s possession.45

We can presume Domenico, a successful Venetian merchant and dealer of hardstones and other antiquities, probably reserved Giuliano’s intaglio for his own commercial or personal interests, seeing that he was likely fond of the prominent Venetian pope and fellow native. Domenico was often on the forefront of events concerning the exchange and acquisition of precious carved-gems throughout Italy and was probably able to reserve and secure Giuliano’s carnelian portrait of the Pope, among various other of Paul II’s antiquarian collection, quite soon after Paul II’s death. Over a duration of time Domenico had sold a number of antique gems to Paul II46 and may have been able to secure Giuliano’s carnelian and other gems, inclusive of the prized Apollo, Marysas and Olympus,47 on probable outstanding debts due to him from Paul II, and thus the Papal Treasury.

Confounding, however, is how or why Cardinal Francesco Gonzaga was in possession of four of these gems from Paul II’s collection in November of 1471. Had Paul II earlier given or loaned these to the Cardinal before he died?48 This seems unlikely despite their good terms. Rather, the answer is simpler given some further context and a bit more data.

Foremost is the realization that these gems were not antique, as has often been assumed. It is noted in the records of Giuliano’s petition to the Apostolic Chamber, that these four gems in Cardinal Gonzaga’s possession were gifts he had given to the Pope, apparently his own creations, which explains why, at the beginning of his petition, he had to give valuations of them based upon what other patrons had offered him for them. It also explains why he willingly suggests not receiving a payment for them and to have them returned to him while receiving payment only for the works he had been contracted to do for Paul II. That is, payment for the carnelian intaglio portrait he had executed for the jubilee as well as payment for a cameo he had worked on for five months whose stone had been imported from France. This latter object is probably the cameo portrait of Paul II which is recorded in Cardinal Francesco Gonzaga’s posthumous inventory of 1483, which Clifford Brown had originally suggested might be a work made by Giuliano.49

The reason Cardinal Gonzaga would have been in possession of these gifts made by Giuliano for Paul II, is because the Cardinal not only had an interest in them for himself, but was also, during this period, quite likely to have been a regular patron of Giuliano’s, as he is documented to have certainly been in the Cardinal’s service a decade later during the early 1480s.50

Cardinal Francesco Gonzaga was one of the few Cardinals Paul II elevated to an influential role within the Curia,51 appointing him the Papal legate to Bologna on 18 February 1471. In addition to this, the Cardinal was also on good terms with Paul II’s loyal cousin, Cardinal Marco Barbo. Both Barbo and Gonzaga together welcomed Borso d’Este on his visit to Rome to receive Paul II’s blessing in becoming the Duke of Ferrara on 12 April 1471, for example. The Pope had unexpectedly died after the Cardinal had just left for his new appointment in Bologna and did not return to Rome until 4 August 1471. We are thus to presume that between this date and the end of November, the Cardinal was able to secure Giuliano’s engraved-gems from the Papal Treasury and this is indeed a probability given that upon his return, Cardinal Gonzaga, along with Cardinals Bessarion and Giovanni Battista Capranica, were tasked by Pope Sixtus IV to draft an inventory of Paul II’s assets.52 It is presumably at this time that Cardinal Gonzaga secured these gems, knowing that he could either later purchase them from Giuliano or return them to him on his behalf. One or more of these gems likely form part of Cardinal Gonzaga’s posthumous inventory: that of a chalcedony Head of Alexander the Great and a large cameo of a cloaked Faustina, also in chalcedony.53

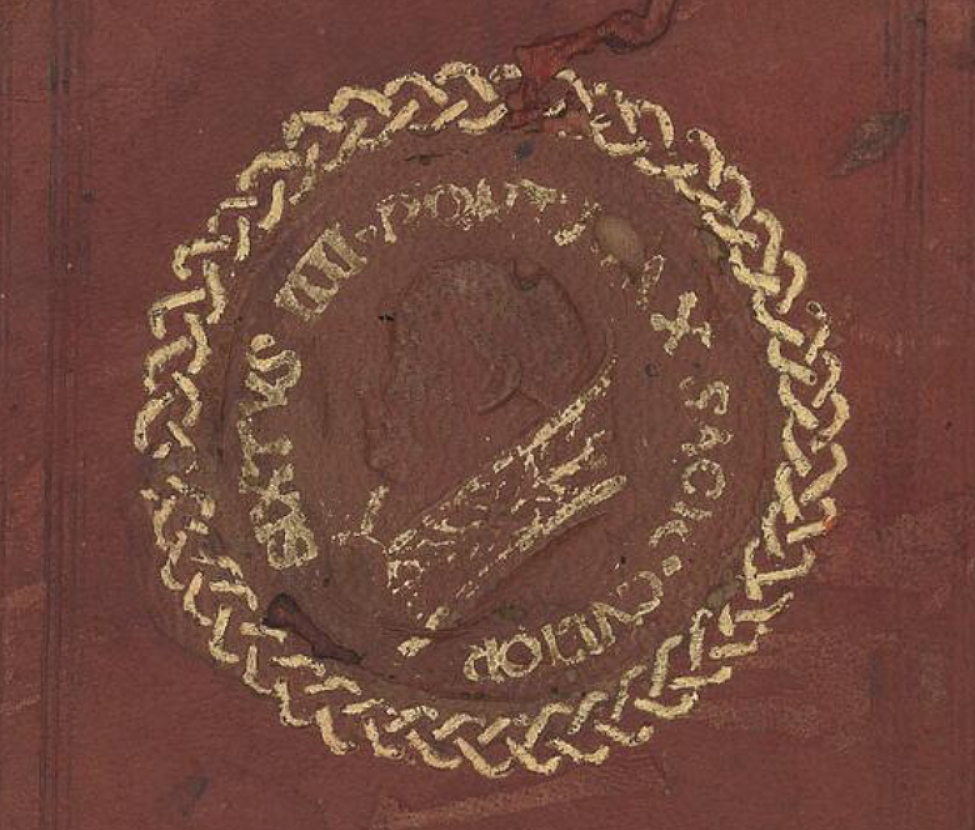

In Giuliano’s carnelian portrait of Paul II, we observe an already accomplished master which must suggest an earlier unidentified repertoire of work, presumably also under Paul II’s patronage and probably also that of Cardinal Francesco Gonzaga, the latter of which is attested by an offer Giuliano had received for one of his gems before 1471 from a certain Galeatio Agnello, whom we identify as a member of Cardinal Gonzaga’s household as late as 1483.54 Of especial note is a signet ring of Paul II from 1464-71, probably used to seal official correspondence (fig. 9). The underside of the ring is inscribed in-relief with the Pope’s title and clearly identifies his ownership of it.55 The surface of the ring depicts facing profiles of Saints Peter and Paul, inspired by early Christian intaglios of the 4th and 5th century and following the tradition of lead seals from the 11th century onward.56 Diana Scarisbrick notes the intaglio on Paul II’s ring was “executed by an artist whose style rivalled that of the best engravers of the age of Augustus, the dignified portraits are lively, combining classical idealization with Christian piety.”57 This achieved naturalism is tantamount to the quality perceived in Giuliano’s portrait of Paul II as well as that of other works, to be discussed.

Fig. 9: Intaglio signet ring of Pope Paul II, probably 1464, possibly by Giuliano di Scipio, Rome (private collection)

In the small effigy of St. Peter, we perceive a precursor to the larger intaglio of Pan (fig. 24)—to be discussed—whose portrait similarly boasts high and narrow cheeks, a thickly protruding upper brow line and wild beard. It could be speculated that this signet ring is the work of Giuliano executed several years before the carnelian portrait of the Pope, and at much smaller scale. Its dependency on antique sources and classical modalities is entirely in line with what would have been Giuliano’s expertise and knowledge.

It should be noted that Giuliano’s petition to the Apostolic Chamber also involved the Chamberlain’s request to have Giuliano update a ‘carnelian of the kingdom,’ possibly for a signet ring, with the new Pope Sixtus IV’s title, as well as a request to ‘redo’ an inscription on a sapphire vessel originally ordered by Paul II, so that it might reflect instead the name of the new Pope.58 Müntz notes that when the body of Sixtus IV was moved in 1610, the papal ring on his finger still had a dedicatory inscription belonging to Paul II: Paulus Venetus Papa Secundus.59 It would seem the former Pope’s successor never completed the task in updating various works earlier commissioned and produced under Paul II’s papacy. Indeed, judging by the sums paid to Giuliano, he does not appear to have fulfilled these requests on behalf of Sixtus IV, at least not in 1471.

Nonetheless, Giuliano’s presumed earlier artistic service to Paul II, could suggest a trusted tenure and relationship characterized by patronage and a shared appreciation for antiquity. Their relationship appears to have been on respectable terms considering the gift of four engraved-gems the Pope had already received from Giuliano. We may also note here the rather informal relationship Giuliano maintained with Cardinal Francesco Gonzaga a decade later, to the degree in which work was completed without any formal contracts,60 and probably also one reason so little documentation survives about this incredibly talented artist.

Paul II’s later commission and reproduction of Giuliano’s intaglio portrait of him informs us of a third important point: that Paul II sponsored the cutting and engraving of modern gems and he took an interest in not only reproducing antique gems from his collection in bronze, but also a contemporaneously made gem, and notably, one made by Giuliano.

This last observation may help resolve questions in plaquette scholarship which have long noted that some all’antica plaquettes derive from legitimate classical gems while others appear to be cast after Renaissance inventions inspired by the antique. It is the present author’s suggestion that Giuliano had an instrumental role in this period of early plaquette production. An immediate observation is that Paul II’s carnelian portrait was made already with the intention of it serving as a model for reproduction in bronze61 or as a seal,62 as the legend on the intaglio is engraved in reverse. It could be presumed that this was not the first time Giuliano had executed a work of this kind, and it is the present author’s suggestion that he is the potential author of one of the most widely diffused and early plaquettes of the 15th century: that reproducing the effigy of the Divine Julius Caesar (fig. 10), to be discussed.63

Giuliano’s feasible exposure to Paul II’s vast collection of antique numismatic objects and more than 821 gems64 would have served as a prime resource for producing contemporary gems inspired by antique glyptics and coins.65 Such an awareness would have provided Sixtus IV the impetus to assign Giuliano the role of assisting in the liquidation of Paul II’s assets in the Papal Treasury. However, it is Paul II’s patronizing of Giuliano which also exemplifies his support for the greatest contemporary artists of his era.

It is possible Cristoforo Geremia may have been witting of Giuliano’s early talents, and possibly during a period before they both fell under the patronage of Paul II. In 1462, Cristoforo cautioned the Marquis of Mantua, Ludovico III Gonzaga, about ‘an excellent craftsman’ making antique cameos in Rome that were counterfeit.66 Whether Giuliano may have been intentional in such a practice during his early career cannot be ascertained67 but if Cristoforo’s comment refers to him, he certainly recognized his capability, and perhaps came to respect his accomplishments when both artists came into the service of the same patron, perhaps even collaboratively. The proposal of Giuliano’s talents in producing convincingly antiquated designs may account for the more than century-long debate concerning the authenticity and age of various all’antica plaquettes discussed in literature on the subject.

Fig. 10: Bronze plaquette of Julius Caesar after a carnelian intaglio here attributed to Giuliano di Scipio, ca. 1466-67 (Palazzo Madama, inv. 1120B)

One of the most influential and widespread all’antica plaquettes is that representing Julius Caesar, previously noted (fig. 10). As with a quantity of other all’antica plaquettes, some scholars have suggested the plaquette representing a profiled bust of Julius Caesar was cast after a classical gem while others have suggested it to be a Renaissance invention inspired by antique models. This latter perspective has received the widest acceptance, especially in recent scholarship.68 The plaquette’s composition appears to derive from a unique blend of both glyptic and numismatic sources, notably a putative portrait of Julius Caesar from the late Augustan era or thereafter, as featured on examples like an amethyst intaglio at the Museo Nazionale in Siracusa69 or a lost carnelian intaglio portrait formerly in the collection of Pierre Louis Jean Casimir, Duke of Blacas (fig. 11).70 71 The unusual modeling of Caesar’s neck particularly seems to derive from such antique glyptic prototypes while the general format of the portrait with Caesar’s cloak, wreath, star and lituus may relate to the Roman portrait coins of the emperor from the 40s BC.72

Fig. 11: Plaster impression after a carnelian intaglio of Julius Caesar, reproduced in 1843 in Trésor de numismatique et de glyptique, formerly in the collection of the Duke of Blacas, and possibly formerly with Cardinal Pietro Barbo (Pope Paul II), before 1471

A majority of plaquette scholars have associated the plaquette with a gem described in Paul II’s inventory as ‘a small head of Julius Caesar in carnelian worth four ducats.’73 Some scholars have further linked this carnelian in Paul II’s collection with one also in Cardinal Francesco Gonzaga’s posthumous 1483 inventory describing a carnelian intaglio of Julius Caesar with the inscription, DIVI JULI, identifying him as the ‘Divine Julius,’74 and clearly related to the plaquette here discussed.75

Scholars have often thought these two carnelians of Julius Caesar to be one-and-the-same on account of Cardinal Gonzaga’s acquisition of a quantity of Paul II’s gems, besides those noted here to be executed by Giuliano, such as antique works like the so-called ‘Felix Gem.’76

However, these two inventory accounts of a carnelian portraying Julius Caesar are possibly two entirely different objects. Namely, the Paul II carnelian is described as ‘small’ and is only given the value of 4 ducats and the inscription, DIVI JULI, is not noted. Cardinal Gonzaga’s carnelian is also valued—at-a-later-date—to be worth 10,000 ducats, to be discussed. Of some note, however, is that the carnelian of Julius Caesar in Cardinal Gonzaga’s inventory is recorded in-between the first listed gem of his inventory: that of the cameo of Paul II, here noted as a possible work by Giuliano, already discussed; and the third gem of his inventory, being that of a chalcedony cameo of Faustina, which we have earlier noted was one of the gems Giuliano originally made as a gift for Paul II and was already in the Cardinal’s possession soon after the Pope’s death. It could stand to reason that the carnelian of Julius Caesar, listed in-between two gems made by Giuliano may inform that it too is a work of Giuliano’s and probably also mounted by him in the gilt silver setting described in the inventory.

If the carnelian of Julius Caesar is Giuliano’s invention, we can stylistically appoint it to an earlier period in his career, sometime before his production of the carnelian portrait of Paul II. Such a production may have been initiated in 1466 when we find in that year, Cardinal Francesco Gonzaga sending a plea to his father in Mantua to borrow a manuscript of Aelius Spartianus so that the text and representations of ancient medals of the Caesars can be referenced because ‘their iconography could not be found in Rome.’77 The Cardinal’s request for this work was intended for use by his court illuminator, Gaspare da Padua, who also happened to be Giuliano’s intermediary for commissions he received from the Cardinal.78 The receipt of this manuscript into the Cardinal’s household is indicative of the interest in such portraits at this date and could place the commission for Giuliano’s Julius Caesar to around 1466-67, a period in which we can assume he had already achieved the graces of both the Pope, and Cardinal Gonzaga.79

It remains uncertain if such a commission would have been executed at the Cardinal’s request or that of Paul II’s.80 Irrespective of this, its possible completion by 1467 would have placed it during the prolific casting activities associated with Paul II’s ‘Officine di San Marco,’ thus encouraging its diffusion through reproductions of it in bronze and probably gesso as well. This idea also foments the notion that the development of plaquettes, with its origins in the reproduction of classical gems and coins—for the sake of preservation and celebration for the antique—emerged with its first contemporary inventions inspired by those same antique sources.81

The diffusion of the Julius Caesar carnelian’s design

A testament to the success of the Julius Caesar carnelian is preserved in the many ways its diffusion served to encapsulate the revival for the antique during the later 15th century and first quarter of the 16th century over a variety of media. The motif’s earliest identified appearance features on an illuminated manuscript produced as early as 1485, to be discussed. However, from this period and into the early part of the next century, it appears as an embossed leather motif on the covers of as many as twenty book bindings executed over a span of several decades in five different locations throughout Italy.82 The motif also appears as a marble tondo at the Casa Botta in Milan, featured on the façade of the courtyard and located just above its entrance.83 As earlier noted, the portrait of Julius Caesar also appears on the interior silver lining of the Shrine of St. Simeon in Zadar, completed in 1497 by the silversmith, Tommaso di Martino (fig. 5, right). A superb gesso or bronze cast of the composition may have passed to that silversmith by way of the shrine’s patron, Maffeo Vallaresso, who visited and stayed with Paul II at the Palazzo di San Marco in 1468, a year after we propose Giuliano completed this work. In 1517 the motif was used in reverse profile, for a woodcut portrait of Julius Caesar depicted in Andrea Fulvio’s Illustrium Imagines, published in Rome.84

Not yet noted in plaquette literature is the feature of the Julius Caesar portrait on a stucco medallion along the lower west wall of an outdoor ambulatory at Horton Hall in England.85 The ambulatory was built for William Knight, ca. 1527-29,86 who was Prothonotary to the Holy See, and later Bishop of Bath and Wells. He visited Rome on numerous occasions, studying at the University in Ferrara and serving as an emissary for the King of England on numerous visits, most notably in 1527 to petition the Pope’s approval for King Henry VIII’s divorce from Catherine of Aragon.87 It is one of the earliest referential uses of a plaquette composition in England with exception of the feature of Master IO.F.F.’s Judgment of Paris inspiring a portion of a frieze along the wood carved mantle of the Great Parlour in Wingfield House, Ipswich, probably made in 1516.88

Also, not well-noted in literature, is the feature of the Julius Caesar plaquette on bronze mortars produced in France, where it appears on at least seven examples datable to the 17th century (fig. 12).89 Other plaquettes descendant of Paul II’s sphere are likewise featured on mortars from this period and Bertrand Bergbauer hypothesizes these models must have initially reached France through Paris during the mid-16th century. This is evinced in part by the presence of terracotta models of these plaquettes which were used as moulds in the pottery workshop of Bernard Palissy, ca. 1510-90, including a mould of the Julius Caesar plaquette.90 91 The interest in incorporating these classical motifs on mortars appears to remain in Southern France throughout the 17th century, where we observe the Julius Caesar plaquette reproduced on mortars made in the workshops of the Master of 1603—active in or around Lyon—and the Master of Provins.92 An interest in the Julius Caesar plaquette a few decades earlier in Lyons, is also observed by a bookbinder who produced a selection of books with this motif on their cover for the library of Marcus Fugger.93

Fig. 12: Bronze mortar with later wooden base, reproducing a plaquette of Julius Caesar, France, 17th century (private collection)

Lastly, Douglas Lewis’ unpublished survey of this plaquette points out its feature on an illuminated miniature equestrian portrait of King Louis XII of France, datable ca. 1498-1503, and featured as one of numerous fictive medallions portraying military heroes along its margins.94 He also notes the motif’s feature on the Ace of Coins from a tarot deck formerly in the collection of Leopold Cicognara, datable to the first decade of the 16th century.95

It is due to this widespread diffusion that the carnelian—sometime after the deaths of Cardinal Gonzaga and Giuliano—that it was apparently mistaken as ancient, as well as remarkably important, and thus valued to be worth 10,000 ducats.96

Proposed origins for the diffusion

of Giuliano di Scipio’s all’antica inventions

While it is apparent Giuliano’s herewith proposed depiction of Julius Caesar was well diffused, this may not have been an arbitrary occurrence, but rather indebted to the immediate Roman environment within which he operated during the 1460s thru to the 1480s and especially by way of his activity surrounding Cardinal Francesco Gonzaga and the retinue of his household, those individuals that were ‘familiares et continui commensals,’97 and who David Chambers notes: “determined the cultural tone of the cardinal’s household in his later years.”98

In beginning this hypothesis, we may follow the subsequent path of the carnelian’s journey. After Cardinal Francesco Gonzaga’s death in 1483, the carnelian was transferred to settle outstanding debts with Francesco’s friend, Alfonso II of Aragon in Naples.99 From this transfer to a Neapolitan environment, we may subsequently note its early reproduction on illuminations tied to that court. Cardinal Francesco Gonzaga’s rapport with Alfonso appears to have borne some influence with his patronized artists in Rome into the Neapolitan environment, most apparent through the previously noted illuminator-miniaturist and antiquaire, Gaspare da Padua, who lived in the Cardinal’s home in Rome and was surely familiar with the carnelian of Julius Caesar.100

In 1485, two years after the Cardinal’s death, Gaspare moved to Naples and entered the service of Cardinal Giovanni of Aragon.101 We may note that as early as 1471, Giuliano also appeared to have had notable ties to Naples, evident by Neapolitans who attempted to purchase his engraved-gems,102 and this could be due to the bonds he shared with his Gonzagan patron and his apparent rapport with Gaspare da Padua. Giuliano’s association with Gaspare is evident in the Cardinal’s requests of Gaspare to commission from Giuliano various works-of-art103 and suggesting that the Cardinal regularly and informally relied upon Gaspare to solicit works from Giuliano which assumes the two of them shared a pre-established acquaintance and working relationship. Gaspare had been in service to the Cardinal since 1466 and is believed to have been trained in the studio of Andrea Mantegna.104 Such camaraderie between Giuliano and Gaspare could be expected as illuminators were often closely linked to goldsmiths, frequently referring to their precious artworks as source material for their elaborate painted border treatments. In 1483, Cardinal Francesco Gonzaga enlisted both Giuliano and Gaspare to help him find antiquities shortly before he died.105

The earliest identified reproduction of the Julius Caesar plaquette is its ornamental feature on the frontispiece of a manuscript of Plutarch compiled by Giovanni Albino and illuminated by Cristoforo de Majoranna in Naples ca. 1485.106 The portrait of Julius Caesar is also reprised in another later Neapolitan work compiled also by Albino alongside Giovanni Marco Cinico in 1494 for Alfonso II of Aragon.107 This latter manuscript’s feature of the Julius Caesar plaquette motif has gone unrecorded in plaquette literature and is attributed to the Neapolitan illuminator Giovanni Todeschino, who worked alongside Cristoforo de Majoranna in the scriptorium of the Neapolitan royal library and workshop (fig. 13, left). More importantly, Todeschino is thought to have been trained by Gaspare da Padua in Rome,108 and could be one further impetus for Gaspare’s eventual departure to Naples in 1485, notwithstanding his probably frustrated pursuit in receiving monies due to him after his Gonzagan patron’s death.109

Fig. 13: Detail reproducing a plaquette of Julius Caesar on an illuminated sheet of Livy’s Decades by Giovanni Todeschino, 1494, Naples (left; US Library of Congress, inv. 2021667740); detail reproducing a plaquette of Diana on an illuminated frontispiece of De evitandis venenis… by Giovanni Todeschino, 1480s, Naples (right; Biblioteca Casanatense, Rome, Ms.125)

Also not formerly noted in previous plaquette literature is Todeschino’s portrayal of the Diana plaquette, to be discussed, which is featured on his frontispiece of a manuscript by Giovanni Matteo Ferrari, De evitandis venenis et eorum remediis, produced in Naples during the 1480s (fig. 13, right).110 It could be surmised that Todeschino could have encountered or acquired gesso or plaquette casts of these compositions during his training in Rome under Gaspare da Padua or could have received examples upon Gaspare’s arrival to Naples in 1485. However, Todeschino would certainly have known the Julius Caesar carnelian after its arrival in Naples in 1483.

Giuliano’s relationship with Gaspare da Padua may, by consequence, also have placed him in the ambit of another Gonzagan resident illuminator and scribe: Bartolomeo Sanvito, with whom Gaspare would frequently collaborate.111 However, Giuliano could have earlier encountered Sanvito during that scribe’s tenure under Paul II between 1464-65.112 While its Roman binding is of a later date, ca. 1515-25, a manuscript of Petrach’s Sonnets and Triumphs,113 scribed by Sanvito, features on its back cover binding, an embossed impression of the Diana plaquette—previously noted and to be discussed.114

Between 1469-71, both Bartolomeo Sanvito and Gaspare da Padua worked closely with the Humanist and antiquaire Julius Pomponius Laetus on the execution of an illuminated manuscript of C. Suetonii Tranquilli duodecim Caesares, probably made for Cardinal Francesco Gonzaga.115 The manuscript exhibits an unusually accurate portrayal of ancient coins and their subjects, representative of the advancement in numismatic knowledge occurring in Rome during this period.116

Pomponius Laetus was one of the most erudite teachers and Humanists in Rome during this period as well as one of the earliest collectors of antiquities in the city. His home on the Quirinal was filled with displays of his coins, statuary, inscriptions, and other antiquities117 and served as a place where ‘unanimes perscrutatores antiquitatis,’118 could gather, learn, and practice living out a lifestyle inspired by the ancient classical past. These gatherings formed what was called the Accademia Romana, engaging in specialized interests revitalizing classical ideals through poetry, literature, food, clothing, and the adoption of classicized names for its principal members.

It is precisely this audience to which Giuliano’s classically inspired designs would have appealed. It could even be assumed he may have been a casual member given his expertise and work. He may have known Laetus directly, but would have likely known others belonging to his circle and academy. For example, we are aware that prior to Cardinal Francesco Gonzaga’s possession of Giuliano’s calcedony of Faustina, it was earlier in the possession of Cardinal Pietro Riaro119 who was a great patron of arts and a friend of Laetus. His uncle was Pope Sixtus IV, whom Giuliano may have served. Riaro’s other uncle was Cardinal Domenico della Rovere, the brother of Sixtus IV, who was made guardian of the Accademia after its reinstatement by Sixtus IV in 1479.120 Another avenue of introduction may have come through Giuliano Marasca who was a pupil of Laetus and the nephew of Bartolomeo Marasca who had served as the household steward for Cardinal Francesco Gonzaga in 1468-69 and had likewise served as the ‘Maiordomus’ for Paul II.121 However, the most direct link would have come by way of another long-time member of Cardinal Gonzaga’s household: Bartolomeo Sacchi, called il Platina, who had been the Cardinal’s tutor during his youth and was one of the core members of the Accademia Romana. He certainly would have seen Giuliano’s creations while in the Cardinal’s possession.

However, there is one further notable member of Cardinal Gonzaga’s household who was likewise a participant in the Accademia Romana, namely Cristoforo Geremia’s nephew: the poet, bronzista and architect, Hermes Flavius de Bonis, also called ‘Lysippus the Younger,’ according to the epithet given him by the Accademia.122 Hermes’ epithet—inspired by the famous 4th century BC bronze worker of antiquity—reflected his prowess in bronze work, a discipline he certainly refined under the tutelage of his uncle, Cristoforo.

It is believed Hermes arrived in Rome as early as 1468 and certainly before the end of 1471, when he executed the first papal coronation medal for the ascension of Pope Sixtus IV.123 Hermes was still an adolescent when he was commissioned to create this work and we are to imagine that he was involved in refining and learning his trade through the prolific bronze casting activities commissioned by Paul II during and leading up to this period.

It could be suggested that the young Hermes may have practiced this art through the casting of uniface plaquettes, involving a simpler process than those required in the production of two-sided medals which he would later prove to be most capable. We may also consider that the young Hermes would have also witnessed or even collaborated with Giuliano in the production of casts made after his carnelian of Paul II while his uncle and mentor, Cristoforo, was also in service to that Pope. Such preliminary experience may additionally have landed Hermes the opportunity to produce Sixtus IV’s medal of 1471, notwithstanding the probable influence of his uncle in obtaining such a commission.124

It is reasonable to suggest that the production of plaquettes in Rome, initiated by the zeal of Paul II, may have continued after his death, sustained in the sphere of Giuliano, Cristoforo Geremia, and by extension, Hermes Flavius de Bonis as well as the overarching interest of Roman Humanists who continued celebrating the classical past. It is worth noting Hermes’ primary patrons were bibliophiles and this may have created an avenue through which Giuliano’s creations spread to other Italian illuminators and bookbinders. Hermes’ primary patron in Rome was the book producer, Giovanni Alvise Toscani and his later Mantuan patron was Cardinal Gonzaga’s brother, Bishop Ludovico Gonzaga, also a bibliophile.125

The last known document we have concerning Giuliano involves his request of the Gonzagan Marquis of Mantua, in 1484, asking for a remaining balance due to him from the late, Cardinal Francesco Gonzaga, for precious jewels and ‘medaglie’ he had sold to him.126 The term ‘medaglie’ during this period is ephemeral and could either refer to coins, medals or plaquettes. This letter from Giuliano also appears to relate to one Gaspare da Padua, had earlier sent to the Marquis mentioning that he had sent silver and bronze ‘medaglie’ to Ferrara and had been instructed to send gems as well. It is presumed these were possible items procured by Gaspare from Giuliano and it remains to be understood if they may refer to medals, plaquettes or coins, yet they suggest the possibility Giuliano may have produced copies of his own works, and if not executed by himself, he may have sourced them to a talent like Hermes who excelled with bronze work and operated among the circle of Humanists probably most prone to appreciate and patronize Giuliano’s work.

Plaquette Bindings

Further suggestive of this idea is the way Giuliano’s inventions were employed regarding their feature in illuminated manuscripts and their use as decorative motifs on the covers of book bindings. A corollary antecedent to this type of diffusion is realized in the work of Hermes whose 1473 portrait medal of Sixtus IV, commemorating the commission for the restoration of the Ponte Sisto bridge, is reproduced, ca. 1475, in a manuscript of the Vitae Pontificum, dedicated to the Pope, illuminated by Gaspare da Padua, scribed by Bartolomeo Sanvito, and written by Platina, thus involving all members of the Gonzagan household. This same medal is reprised by these artists on the frontispiece of Aristotle’s De animalibus,127 ca. 1473-75, and again on a presentation copy of Plutarch and Seneca copied by Sanvito in 1477.128 This same medal by Hermes also represents the earliest feature of a Renaissance medal on a book binding: embossed in leather on a Roman binding, ca. 1475-78, of St. John Chrysostom’s sermons by Andrea Brenta, and scribed by Sanvito (fig. 14),129 who himself may have been responsible for inventing this binding.130

Fig. 14: Stamped leather bookbinding of St. John Chrysostom’s sermons, probably bound by Bartolomeo Sanvito, ca. 1475-78, after a portrait medal of Pope Sixtus IV made by Hermes Flavius di Bonus in 1473 (Vatican Library, vat. lat. 3575)

We may thus observe that this circle of artists tied to Cardinal Gonzaga, were the first to deploy the copying and reproduction of contemporaneously made all’antica devices within the Humanistic milieu of Rome beginning from the mid-1470s and among those connected loosely or intimately with the Accademia Romana. A testament to the collecting activities of these individuals is already noted briefly in the habits of individuals like Laetus and Cardinal Gonzaga but is also attested in Sanvito’s own lost Memoriale which described him as a ‘cultivated amateur,’ whose cabinet was filled with ‘jewels, cameos, gold and silversmiths works, coins and medals.’131 We may thus observe Giuliano’s proximity with these events, his connection with the Gonzagan household, and the subsequent appearance of his own all’antica devices finding their way onto bindings and illuminated representations in manuscripts.

Giuliano’s inscriptions

Another event closely tied to the literate sphere of the Accademia Romana is the advent of the first printing press in Rome. The immense influence of the Accademia Romana on the editing and publishing of books in late 15th century Rome is already thoroughly outlined by Maria Grazia Blasio,132 however, we may note, for example, the influence of members like Giovanni Antonio Campani, and also members of the Papal Curia like Cardinal Bessarion and the Pope’s cousin, Cardinal Marco Barbo, who advocated for the introduction of the printing press with much controversy.133 The literate sphere of the Accademia is further emphasized in the Cardinal’s former house-guest, Platina, who was later appointed as Papal Librarian by Pope Sixtus IV, a role that was to be even later assumed by another of Cardinal Francesco Gonzaga’s friends: Pietro Demetrio Guazzelli da Lucca.

When the German monks, Arnold Pannartz and Konrad Sweynheim, arrived just outside of Rome to establish the first printing press at the Monastery of St. Scholastica in Subacio, they produced the first books in a half Roman type to meet the demands and interests of the Humanists involved in sponsoring this effort. In 1467, they relocated their operation inside of Rome at the Palazzo Massimo.

The introduction of movable type in Rome required that cutting punches, striking matrices, and moulds for casting type were needed. This work, during this period in history, was allocated to the realm of goldsmiths, and particularly those experienced with the production of coins or medals. While such type could have been executed by other Germans emigrating to the region to work for the new print industry of Italy, the expertise required to understand the foreign Humanist script would have been arduous for those acclimated to the blackletter types of the north. Rather, more accessible artists among Rome’s goldsmiths may have been a better solution, and this indeed appears to be the case. Riccardo Olocco’s novel research on this subject has brought to attention a company formed in Rome during the late 1460s which included four unidentified Roman goldsmiths ‘to compose and produce books with [letter] forms.’134 The company was to last for a term of five years and we may readily associate this with Rome’s first press within the city, which was begun in 1467, yet had come to an end by 1472. We could wonder if Giuliano may have been one of the four goldsmiths involved in this enterprise given his proximity with those active in-and-around the Cardinal Gonzaga’s retinue as well those attached to the Accademia Romana.

Giuliano’s proximity with Gaspare da Padua, and by consequence, his collaborator, Bartolomeo Sanvito, would have made him readily familiar with the contemporary use of the Humanist scripts being employed in Rome at this time. His requests to execute inscriptions on hardstone may also have been impetus to get involved in such an enterprise. Notably, Sanvito’s script closely followed that of Laetus’ own personal script and the amalgam of their styles appear to have greatly influenced the first letter types used on Rome’s printing press.135

The inscribed text observed on Giuliano’s carnelian portrait of Paul II as well as that featured on the plaquette casts of the carnelian of Julius Caesar, here attributed to him, use the Humanist minuscule form script, dubbed in that period as the ‘litterae antiquae’ manner. This type was espoused by Giovanni Andrea Bussi, the first Papal Librarian appointed by Paul II and a close friend of Cardinal Bessarion. He was the lead print editor for this first printing press set-up in Rome in 1467. The detail to which Giuliano gives to his inscriptions is tantamount to these practices occurring in the academic environment within Rome and suggestive of his presence in the midst of it all.

We may note here the various matrices which faithfully reproduce the intaglios and cameos ascribed herein to Giuliano, which were possibly made with the intention of stamping leather for the bindings of books (fig. 15). The concept of this production is generally related to the processes involved in producing typecasts for the printing press. However, they may also have been used to produce multiples in gesso to sell or distribute among collectors. It cannot be determined whether such matrices may have been produced by Giuliano, insofar as their use on bindings might be concerned, as most survivals of these bindings date to the first quarter of the 16th century, and we are to presume, by that time, Giuliano had passed-away. Nonetheless, it would appear, at a minimum, that superb examples of Giuliano’s compositions must have survived among book processing workshops to allow such quality matrices to be produced or to have survived beyond Giuliano’s lifetime.

Fig. 15: Bronze plaquette matrices of Julius Caesar (left) and a Bust of a Classical Youth (right) used for stamping leather bindings for book covers (Museo Nazionale del Bargello, invs. 621B and 153B)

Giuliano’s proposed activity in the sphere of the Accademia Romana may have been a tangible avenue through which his all’antica designs spread among Italy’s Humanist audiences and encouraged their continued life in other media and especially those regarding the dissemination of literature.

Other works by Giuliano in Rome

In addition to the plaquette of Julius Caesar, there are various others within the category of all’antica plaquettes, believed made during the Renaissance, which may stylistically—and to some degree, contextually—be associated with Giuliano.

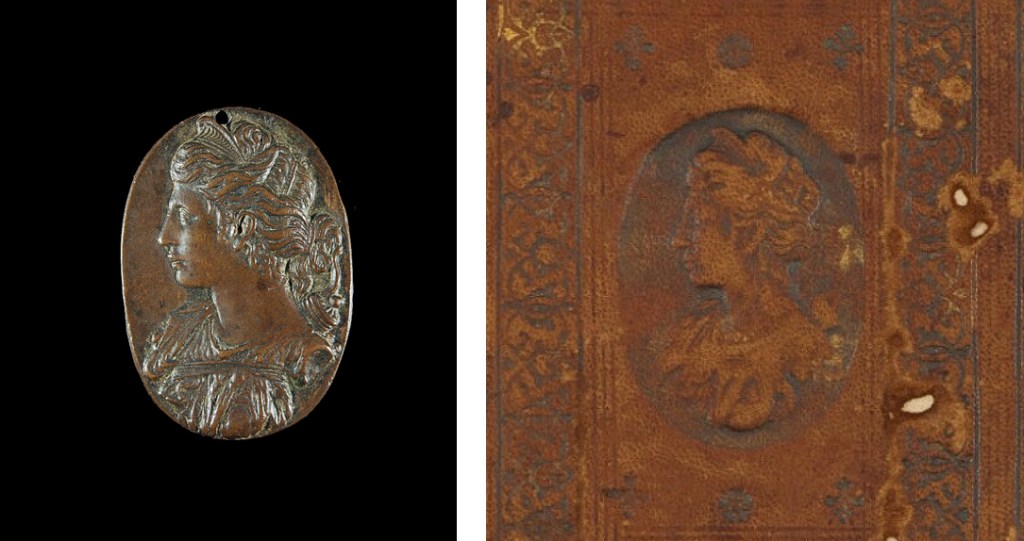

A rare plaquette depicting a Bust of a Classical Youth (fig. 16, left) is the earliest plaquette design identified on a book binding. The design is incorporated on the cover of the Codex Lippomano (fig. fig. 16, right), a collection of Latin epigrams and poetic verses dedicated to its recipient, Niccolò Lippomano, and composed by Jacopo Tiraboschi, which he presented to his classmate to preserve the memory of their academic experiences in Padua. The manuscript was originally presumed to have been bound not long after 1471,136 however, it has been more recently suggested that the poems Jacopo prepared in this volume may not have been written until a later date, ca. 1478-80, as some of them are addressed to students at the University who were not present there until this later period.137 Nonetheless, its binding follows not long after that observed of Hermes’ feature of his medal on the manuscript of St. John Chrysostom’s sermons, previously discussed (fig. 14). The execution of the Lippomano manuscript is attributed to Felice Feliciano,138 who was also responsible for its binding, as typical of scribes from this period. Plaquette bindings may indeed have derived from the recruitment of goldsmiths who would have furnished the accessories for a binding, namely the clasps, catches, corner pieces and central medallions applied to their covers. Such objects were, during these early dates, the commission of scribes and manuscript illuminators who would bind their own works.

Fig. 16: Bronze plaquette Bust of a Classical Youth (Antoninus or Caracalla?), after a gem here attributed to Giuliano di Scipio, before 1471 (left; Mario Scaglia collection); and a detail of the cover binding of the Codex Lippomano, reproducing a Bust of a Classical Youth (right; Morgan Library, inv.199044)

The Lippomano binding is unique from other plaquette bindings in that it incorporates a gesso cast of the plaquette inset beneath its leather cover. The binding was recently subjected to scientific tests and a hypothetical recreation by Yungjin Shin of the Thaw Conservation Center. His analysis noted that a metal or wood plate would have also been used to assist in stamping the plaquette’s design onto the leather binding in addition to incorporating the gesso inset,139 being in-keeping with the various other plaquette bindings that do not incorporate a gesso inset but rely rather on stamping the leather with an impression. Shin also observed the use of trace red beads of resin or glass that were once patterned over the brushed gold ground surrounding the plaquette motif which, in its original state, likely filled the entire negative space surrounding the relief, creating a beautiful glowing red texture atop the gold ground. This same technique was employed on other bindings by Feliciano and would suggest further evidence for Hobson’s attribution of the binding to that maker.140 The plaquette appears on at least six additional bindings141 made in Padua, Rome and Naples, the latter of which is the latest, ca. 1515-35, and corresponds with a later circular variant of the relief.142 One example of a matrix used for stamping this relief into the leather covers for bindings is preserved at the Museo Nazionale del Bargello (fig. 15, right).143

There are several means by which this early plaquette, here attributed to Giuliano, may have reached Feliciano. Feliciano had been in Rome in 1478, just prior to the execution of the manuscript and its binding, and furthermore, Feliciano was a friend of Cristoforo di Geremia during their youthful years in Verona. He wrote two sonnets of praise to Cristoforo during the 1450s, for example.144 It could be presumed he acquired this gesso example of Giuliano’s composition while in Rome and may also have learned about or observed the feature of Hermes’ medal of Sixtus IV embossed on the cover of the manuscript of St. John Chrysostom’s sermons.

That Cristoforo Geremia was a friend of Feliciano’s led Anthony Hobson to suggest the Bust of a Classical Youth may have been his work.145 However, this seems unlikely since Cristoforo is not securely known to have produced any plaquettes,146 although we here retain the notion that Cristoforo may have been involved in producing casts of it on account of his proximity with Giuliano. The bust has also been thought to portray Antinous among others,147 and could possibly relate to a chromium chalcedony belonging to Cardinal Francesco Gonzaga as noted in his posthumous inventory.148 However, due to its feature on a Florentine manuscript of Ptolemy’s Geografia, ca. 1476-90, by Attavante degli Attavanti or Boccardino il Vecchio (fig. 17, left),149 it is thought the composition could equally relate to a gem of Caracalla owned by Lorenzo de’ Medici. The manuscript’s frontispiece upon which this design is featured likewise includes other cameos certain to have been in Lorenzo’s collection.150 However, this gem may have been part of one or two groups of Cardinal Francesco Gonzaga’s gems that travelled to Florence twice in 1484: in March and October, respectively, while Lorenzo was contemplating purchasing items from the Cardinal’s estate to settle debts owed to the Medici bank in Rome.151 At this time, Lorenzo may have commissioned plaster casts of several of these gems to keep for the purposes of decision-making concerning their purchase. However, the last group of gems, delivered in October, seem to have remained in Florence for almost four years, until being sent back to Rome in 1488. This provided plenty of time for Florentine illuminators to become familiar with various of Cardinal Gonzaga’s gems, possibly incorporating them into their manuscripts datable to this period.152 However, this plaquette’s feature on these manuscripts, dependent on when they were made, may also indicate it was one of the objects from Paul II’s collection which Lorenzo may have acquired in 1471 and could also attest to its Florentine presence, if unrelated to the Antinous gem listed in Cardinal Gonzaga’s inventory.

Fig. 17: Details of a frontispiece of Ptolemy’s Geografia depicting illuminations by Attavante degli Attavanti or Boccardino il Vecchio, ca. 1476-90, after plaquettes of a Bust of a Classical Youth (left) and Head of Minerva (right) (Bibliothèque Nationale, MS. lat. 8834, fol. 1)

Christopher Fulton thought the Bust of a Classical Youth may have been inspired by numismatic and glyptic portraits of Mithridates VI Eupator, king of Pontus (120–63 B.C.).153 and Lewis compares it to the chalcedony intaglio profile of the ‘Strozzi Medusa’ executed in the 1st BC by Solon.154 This amalgam of various prototypes speaks to Giuliano’s working methods in creating fictive portraits in all’antica manner.

To recall that Giuliano may have conceived Paul II’s carnelian portrait with the intent to also reproduce bronze examples is furthered in Douglas Lewis’ comment of the Bust of the Classical Youth which he notes is: “so unusually crisply rendered, it may well be possible that this plaquette design was originated directly by a Renaissance artist accustomed to bronze casting.”155

In 1989 Francesco Rossi noted technical similarities between the aforenoted Bust of a Classical Youth and a plaquette depicting Athena or Minerva (fig. 18, left).156 The latter may have been one of two busts of Athena listed in Lorenzo de’ Medici’s posthumous inventory, considered lost.157 One ancient example from Lorenzo’s collection—of Hellenistic or early Augustan import—survives in the Museo Archeologico in Florence.158 Suggesting that the plaquette may preserve the other lost example in Lorenzo’s inventory is reinforced by its feature on Florentine manuscripts, namely the previously discussed copy of Ptolemy’s Geografia of 1476-90 (fig. 17, right), and more particularly on a Missal of Thomas James illuminated by Attavante which offers a secure date of 1483 and precedes the period in which Cardinal Gonzaga’s gems were in Florence.159 The plaquette also appears on bindings, the earliest being attributable ca. 1505-15,160 and appears also on the interior silver lining of the Shrine of St. Simeon in Zadar, previously discussed (fig. 5, left). If owned by Lorenzo, it could be concluded he had acquired it from Paul II’s collection in 1471.

Fig. 18: Bronze plaquette of a Head of Minerva, after a gem here attributed to Giuliano di Scipio, before 1471 (left; Grassimuseum, lost in WWII) and a bronze plaquette of Julius Caesar, possibly after a gem by Giuliano di Scipio, probably before 1466 (Museo Nazionale del Bargello, inv. Dep. p.10.)

Lorenzo’s acquisition of gems from Paul II’s estate is inferred by a document from Lorenzo’s Ricordi of September 1471 and correlates with his visit to Rome while establishing Medici banking relations with the newly installed Pope Sixtus IV.161 This is precisely the period in which Giuliano may have been actively brokering or advising in the sale of Paul II’s gems in Rome and Laurie Fusco and Gino Corti equally suggest Giuliano’s possible involvement in Lorenzo’s acquisition of various of the Pope’s gems.162 Such an occasion may have also introduced Lorenzo to Giuliano’s talents, to be discussed, and particularly after having recently executed the successful carnelian portrait of Paul II.

On a tertiary note, Jeremy Warren has made an interesting observation concerning a rare plaquette of Julius Caesar that may relate to the Minerva plaquette (fig. 18). They share the same style of cuirass and a similar scale. However, the bronze casts which preserve the memory of this composition seem to be a later production probably after the 15th century (fig. 18, right). They feature a crudely articulated inscription: IVLIVS CAESAR DICTATOR, which has been added to an impression of what was an originally blank ground. Remarkably, the collection of gesso casts taken by Tomasso Cades in the early 19th century reproduce what must be the now lost gem (fig. 19). This could represent another production by Giuliano as its character closely relates to the inscribed carnelian of Julius Caesar and is possibly a precursor to it. However, it almost certainly uses the carnelian intaglio of Julius Caesar formerly in the Duke of Blacas’ collection as its point-of-reference (fig. 11), inclusive of the cuirass, which would encourage one to suggest that the Blacas carnelian of Julius Caesar may have been the example once owned by Paul II and described in his inventory, and thus also immediately familiar to Giuliano.

Fig. 19: Tomasso Cades’ early 19th century plaster impression of a lost gem of Julius Caesar, possibly by Giuliano di Scipio, before 1466, based upon a carnelian possibly once in Paul II’s collection (see fig. 11)

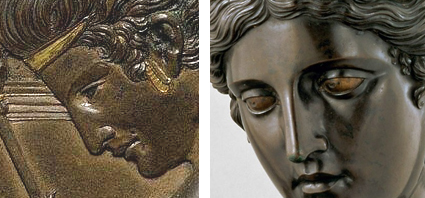

Giuliano appears to later evolve his composition of Minerva into a larger fictive portrayal of Alexander the Great. This idea is reinforced by the inscription: ALISANDRO (fig. 20, left) featured on a majority of known casts.163 However, this inscription is quite likely a later addition to one of the moulds taken from the original gem. A ‘first state’ of this plaquette, not very well known since the majority of them are in private collections (fig. 20, right), lacks the inscription and more faithfully reproduces the original gem. The Alexander the Great plaquette retains the same styled cuirass, facial type, and near-similar helmet to that of the aforenoted Head of Minerva although exchanges the helmet’s portrayal of a triton blowing a conch with an alternative scene of a contest between a centaur and lapith. Just as the plaquette of Julius Caesar, this example of Alexander the Great also served as the model for the portrait of Alexander the Great featured in Andrea Fulvio’s Illustrium Imagines, published in 1517 (fig. 21).

Fig. 20: Bronze plaquette of Alexander the Great with inscription (left; National Gallery of Art, DC, inv. 1942.9.202) and a bronze plaquette of Alexander the Great, without an inscription (right; Mario Scaglia collection), after a presumably lost white chalcedony engraved-gem here attributed to Giuliano di Scipio, before 1471.

Fig. 21: Detail of a woodcut from Andrea Fulvio’s Illustrium Imagines, 1517, after a composition here attributed to Giuliano di Scipio

Not yet noted in plaquette literature is the partial portrayal of this composition as an illuminated miniature double-portrait featured in a copy of Petrarch’s Triumphs scribed and illuminated around 1480 by Bartolomeo Sanvito and Gaspare da Padua.164 While the cuirass on the illuminated portrayal of Alexander is different from that of the plaquette, the face, hair and especially the helmet—which depicts the previously noted contest between a centaur and a lapith—is an exact copy (fig. 22). It would also appear that this double-portrait of Alexander has been superimposed over a second portrait of what looks like a profile of Cardinal Francesco Gonzaga, presumably associating him with the prestige and accomplishment of the ancient hero and perhaps related to his role as legate during the War of Ferrara in 1482-83.165 It is notable the Cardinal’s own armor, or cuirass, related to this event, formed part of his belongings after his death166 and we are to wonder if this miniature might depict it. This large plaquette of Alexander the Great may very likely reproduce the ‘chalcedony head of Alexander’ Giuliano originally gave to Paul II as a gift and was subsequently kept in Cardinal Gonzaga’s possession after the Pope’s death and consequently owned by the Cardinal, described in his posthumous inventory as: ‘Alexandro Magno in calcedonio biancho ligato ut supra cum cadenella.’167 This would also explain its partial feature on the aforenoted manuscript, as both Gaspare and Sanvito would have seen the chalcedony of Alexander the Great in the Cardinal’s household, thus using it as a reference for the miniature double-portrait.

Fig. 22: Bronze plaquette of Alexander the Great, after a lost chalcedony here attributed to Giuliano di Scipio (left; Mario Scaglia collection); detail of an illuminated sheet from Petrach’s Triumphs by Gaspare da Padua and Bartolomeo Sanvito, ca. 1480-83, presumably a double-portrait of Alexander the Great and Cardinal Francesco Gonzaga (right; Walters Art Museum, inv. W755)

The Alexander the Great composition also appears on four surviving book bindings, all noting the subject of the portrait: two with the text, ALESANDRO and two with the Greek spelling of the hero’s name.168 It is perhaps due to the association of the plaquette with these bindings that a later workshop decided to add the inscription ALISANDRO to subsequent casts of the plaquette (fig. 20, left).

One further plaquette emerging from Paul II’s orbit, also featured on the previously discussed shrine in Zadar, is one depicting Diana (fig. 23, left). Although traditional plaquette literature has placed its origin around the year 1500, Jeremy Warren has recently noted it served as a reference for a right-facing portrait profile on the wheel of a chariot in a stone relief dating from the 1480s, and executed by a sculptor active in Cremona.169

Fig. 23: Bronze plaquette of a Bust of Diana (left; AD & A Museum, inv. 1964.524); detail of a stamped leather Roman binding after a plaquette of Diana, ca. 1510-20 for a copy of a Greek Psalterion (right; private collection)

Further suggesting an earlier origin is the appearance of this plaquette on a bookbinding for a copy of Asconius Pedianus’ Commentarii in orationes Ciceronis, printed in Venice sometime after 2 June 1477, and probably bound ca. 1480-95, as adjudged by Anthony Hobson.170 The Diana plaquette is likewise reproduced on seven additional bindings produced in Florence, Rome (fig. 23, right), and Milan between ca. 1497 and ca. 1525,171 and three matrices of the plaquette survive in various collections. Its success is likewise proved by the quantity of casts which survive in numerious private and public collections.172

Not noted in previous plaquette literature is Neil Goodman’s observation that this motif appears in a tromp l’oeil stone tondo forming part of the wall frescos in the Abbazia-Lazzari Chapel at Verona Cathedral attributed to Antonio Badile II during the late 15th century.173 An additional early portrayal, also not yet noted, is its feature on the frontispiece of a manuscript by Giovanni Matteo Ferrari, De evitandis venenis et eorum remediis, copied in Naples in the 1480s by the previously noted illuminator Giovanni Todeschino (fig. 13, right),174 a presumed pupil of Gaspare da Padua.

Rather than borrowing from classical gems, the bust of Diana instead appears to depend on ancient coins of Greek and Hellenistic origin. Lewis suggests its closest parallel to be that of a hundred litrai coin struck for Agathocles of Syracuse, in Sicily around 300 BC.175 Paul II’s collection of coins would have been an adequate source from which to have developed this composition which Lewis notes is an “impressively resolved design which may well have been an original creation, based on a variety of antique numismatic and/or glyptic inspirations, by a remarkably accomplished artist of the 1460s or early 1470s.”

Other works by Giuliano in Florence

As previously noted, the gem of Minerva and possibly that of the Bust of a Classical Youth, here ascribed to Giuliano, appear to have reached Florence possibly as part of Lorenzo de’ Medici’s acquisitions from Paul II’s estate in 1471 or alternatively acquired from Cardinal Gonzaga’s estate in 1484.176 Encouraging this idea is their tandem appearance on the previously discussed frontispiece of Pliny’s Geografia (fig. 17). However, it is unclear if Lorenzo would have understood these to be contemporary inventions or antique. We may note that in 1489, when the goldsmith Caradosso Foppa visited Florence and saw Lorenzo’s collection, he noted one gem—believed to be antique—was judged by him to be modern.177

It remains evident, however, that Lorenzo did commission contemporary works, as observed by several surviving gems from his collection now at the Archeological Museum of Naples, inclusive of a Maenad, to be discussed. His interest in both antique and contemporary glyptic art may also have been encouraged by his loyal secretary, Niccolò Michelozzi, who also collected both antique and modern gems. Giorgio Vasari also paints for us the image of Lorenzo as a revivalist of glyptic art in Florence.178 In 1477, the medallist Pietro de’ Neri Razzanti may have arrived in Florence to teach gem engraving but it remains questionable whether this was at Lorenzo’s request.179 Nonetheless, we are aware of Giovanni delle Corniuole and Pier Maria Serbaldi da Pescia, who were together tasked to evaluate the Medici gems after Lorenzo’s death in 1492,180 and who must have had an early start to their careers in Florence, probably on account of Lorenzo’s patronage. Certainly, the cameo portrait of Lorenzo attributed variably to the aforenoted Giovanni or to Domenico de’ Cammei is an example of his sponsorship of this art.181

While no documentary evidence has come to light concerning Lorenzo’s patronage of gem-engravers, the earlier occasion of Lorenzo’s sojourn to Rome in 1471 may have introduced Lorenzo to Giuliano’s talents in this field while acquiring objects from Paul II’s collection. It should also be noted that Giuliano, if operating in the circle of the Accademia Romana, may have also had convenient ties to Florence through members of the academy like Cardinal Giacomo Ammannati and Agostino Campano Settimuleio, both of whom were important Humanist contacts between Rome and Florence and friends with Gentile Becchi, who had served as the private tutor of Lorenzo during his youth.182 It is also worth noting that Bartolomeo Sanvito, in 1474, produced a revised manuscript of De optimo cive which was presented to Lorenzo in that year.183

We know nothing of Giuliano after 1471 until he reappears, still in service to Cardinal Francesco Gonzaga, in Rome, in 1483. If Giuliano did spend a brief period in Florence, he may have been drawn there not long after Cristoforo Geremia’s death in 1476 or perhaps sought to extend his patronage to an important collector like Lorenzo.

As a patron of artists, Lorenzo embellished his gem collection with contemporary examples relative to his interests and the present author has previously suggested an intaglio rock crystal depicting the Head of Pan could be Giuliano’s invention (fig. 24).184

Fig. 24: Rock crystal intaglio of a Head of Pan, here attributed to Giuliano di Scipio, ca. 1480 (private collection)

The intaglio of Pan shares several similarities with Giuliano’s portrait of Paul II beyond their left-facing profile busts and shared widths; like the small tuft of hair peeking from the base of Barbo’s crown, rendered in a manner close to Pan’s as well as the curved strokes delineating the eyebrows on each gem, both engraved in alike manner. Additionally, the smoothly curved contours along the edge of the noses and the modeling of the faces share a similar gelatinous-like luminous distinction. The pupils on both are carefully drilled just slightly beyond the orb of the eye and the palmettes extending from Barbo’s triple crown papal tiara terminate in sharply chiseled, angular hooks in the same manner as the wild hair protruding from Pan’s forehead (fig. 25).

Fig. 25: Detail of a rock crystal intaglio of a Head of Pan, here attributed to Giuliano di Scipio, ca. 1480 (left; private collection) and detail of a carnelian intaglio portrait of Pope Paul II by Giuliano di Scipio, 1470, Rome (Palazzo Pitti, Museo degli Argenti, inv. Gemme no. 323)

There are also shared correspondences between the intaglio of Pan and that of the Julius Caesar composition (fig. 41). Foremost is their alike format, having been carved in intaglio atop a convex surface and thus prompting their bronze reproductions as plaquettes to be incuse on casts of the finest examples. The similar depth of modeling and alike convex character is observed in placing examples of these plaquettes side-by-side (fig. 26).