by Michael Riddick

Download / Preview High-Resolution PDF

Antonio Gentili was born in Faenza in 1519 to the goldsmith Pietro Gentili and his wife Ginerva Aremenini. Antonio followed in the goldsmith’s trade of his father who had a workshop in Faenza. In his late teens and early twenties Antonio would have observed his father’s role as prior in the Society of San Michele in Faenza and as a member of the Faenza Confraternity of the Battuti Rossi.1 Antonio’s observation of his father’s participation in these societies were a possible influence on him that precipitated his future service in organizational roles like Chamberlain and Consul member of the Confraternity of Goldsmiths in Rome and later as Assayer of the Papal Mint.

Antonio’s choice tenure in these institutions is noteworthy as some goldsmiths appear to have operated independent of traditional guilds like Benvenuto Cellini, for example.2 We can assume Antonio had an esteem for traditions and a possible conservative disposition to his personality and this likewise informs of his workmanship which is in-keeping with the conventional tastes of his time and perhaps only approaching audacity by his aptitude and standard for technical virtuosity and elegance to which he was to be praised in comparison with that aforenoted Cellini.3

Judging by the quality of his productions, Antonio was detail-oriented and an apt problem-solver, capable of integrating an ensemble of various parts into a seamless and technically accomplished work-of-art. Even more so was his ability to achieve an outstanding harmony in his workmanship, being less reliant on richly executed individual parts and excelling in an elegant language of ornament meets figural form. This ingenuity is observed in his earliest known surviving work, the Farnese Altar Service (no. 1, cover), comprised of two complex decorative candlesticks and an altar cross intricately formed by a series of individually prepared parts and boasting as many as forty-six individually realized sculptural components which exemplify the zenith of Antonio’s talents.

Antonio’s commitment to his work and his presumed conservative disposition might also be responsible for his rather late marriage to Costanza Guidi in June of 1561, at approximately the late age of forty-two. However, a dispute concerning matters of jealousy regarding a certain Faustina, eight years prior, might indicate an earlier unrequited love.4 By the time of Antonio’s marriage to Costanza he is already an established goldsmith. The couple had three children together: Alessandro, Pietro and Geneva. Their middle-child, Pietro, would adopt the goldsmiths trade and later succeed Antonio as Assayer of the Papal Mint in 1602.5 Pietro may have been involved in the realization of the relief depicting the Skills of a Prince (no. 4) and documents cite Pietro’s participation alongside Antonio in earlier projects like a cross realized for the Monastery of San Martino in Naples in 1593—probably destroyed in 17946 (no. 37)—and on certain unknown works for Cardinal Federico Borromeo.7 8

The earliest recognition of Antonio as a goldsmith is a document from Rome in 1552 and sources indicate his presence in the city as early as 1549-50.9 Antonio’s earliest documented commission involved the production of twelve silver reliquaries he made in collaboration with the silversmith Pier Antonio di Benevenuto for Pope Pius V in 1570 (no. 14).10 During the 1570s Antonio would gather commissions from numerous other important patrons like Duke Muzio Mattei and Cardinal Ferdinando de’ Medici.11

Antonio’s most important commission, the Farnese Altar Service, completed for Cardinal Alessandro Farnese, would come by way of inheriting a project left unbegun or incomplete by Manno di Bastiano Sbarri following that goldsmith’s death in 1576.12 That the Cardinal entrusted Antonio with the completion of the Altar Service implies his repute and trusted capability by this time.

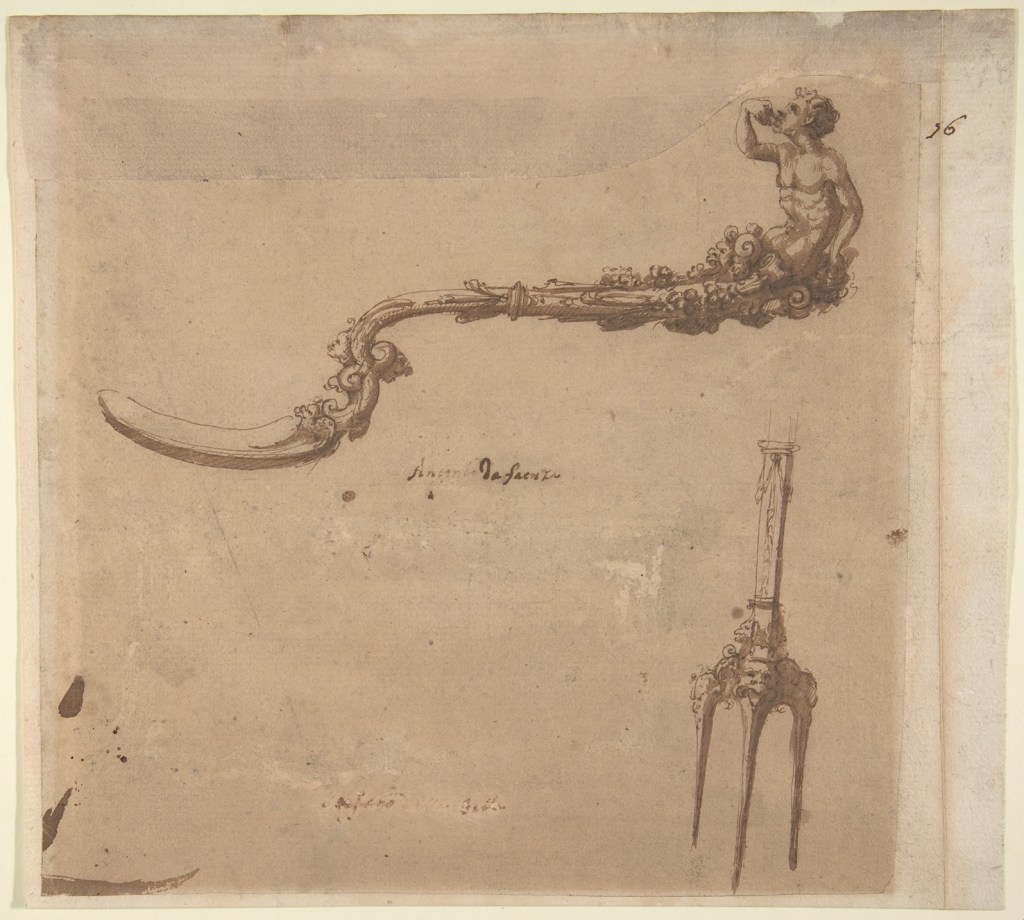

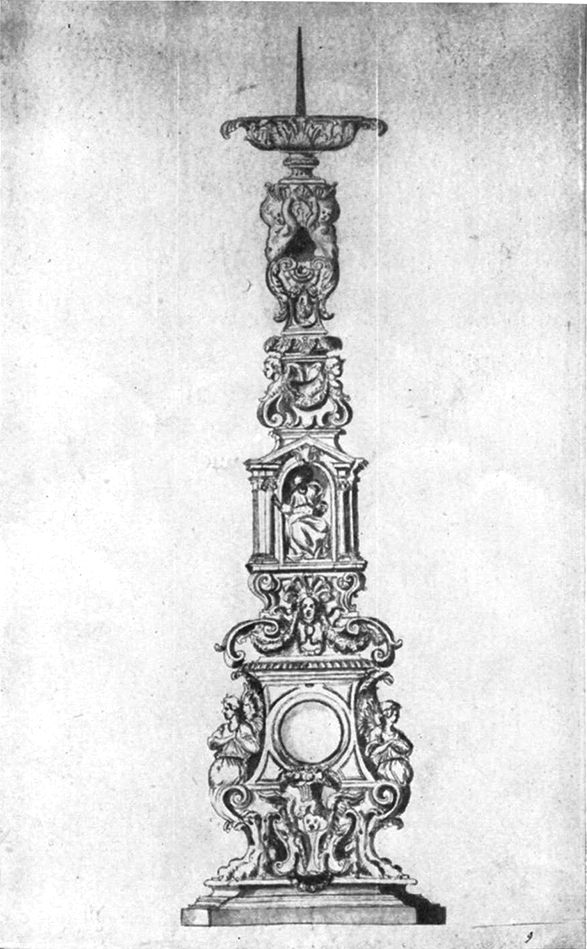

Fig. 1: Drawing of a Candlestick or Altar Cross base attributed to Francesco Salviati and workshop (unidentified collection)

Although nearly two decades of Antonio’s activity between 1552-69 produces no body-of-work with which to refer, we can assume he mastered his tradecraft during this time, increasing his associations with others of his profession and developing a network of patronage. There is reason to suggest his work was profoundly influenced during this time by the creativity of the painter and draughtsman Francesco de’ Rossi (called Francesco Salviati) who presumably furnished designs for the celebrated Farnese Casket by Sbarri13 (fig. 14) and likewise provided the designs for the Farnese Altar Service.14 While no evidence of a friendship between Antonio and Salviati is found in sources, Salviati’s frequent presence in Rome during this period and his documented camaraderie and collaboration with Sbarri in Rome, could lead to the assumption Salviati and Antonio were possibly acquainted. Antonio certainly owned drawings by Salviati which he had acquired through the sculptor and draughtsman Guglielmo della Porta.15

Fig. 2: Engraved print of Designs for Cutlery by Cherubino Alberti, 1583, after Francesco Salviati (Victoria and Albert Museum, inv E.1722-1979)

A sheet attributed to Salviati, of an elaborate candlestick or altar cross base, exhibits characteristics tantamount to the decorative language observed throughout Antonio’s body of work (fig. 1).16 Also synonymous is a sketch of a chalice by Salviati which appears to echo the Mannerist muses and interlocking putti found on Antonio’s Farnese Altar Service (fig. 3). Additionally, a pair of silver cutlery pieces attributed to Antonio (no. 5) are inspired by Salviati’s templates which were recorded in an engraving by Cherubino Alberti in 1583 (fig. 2).17

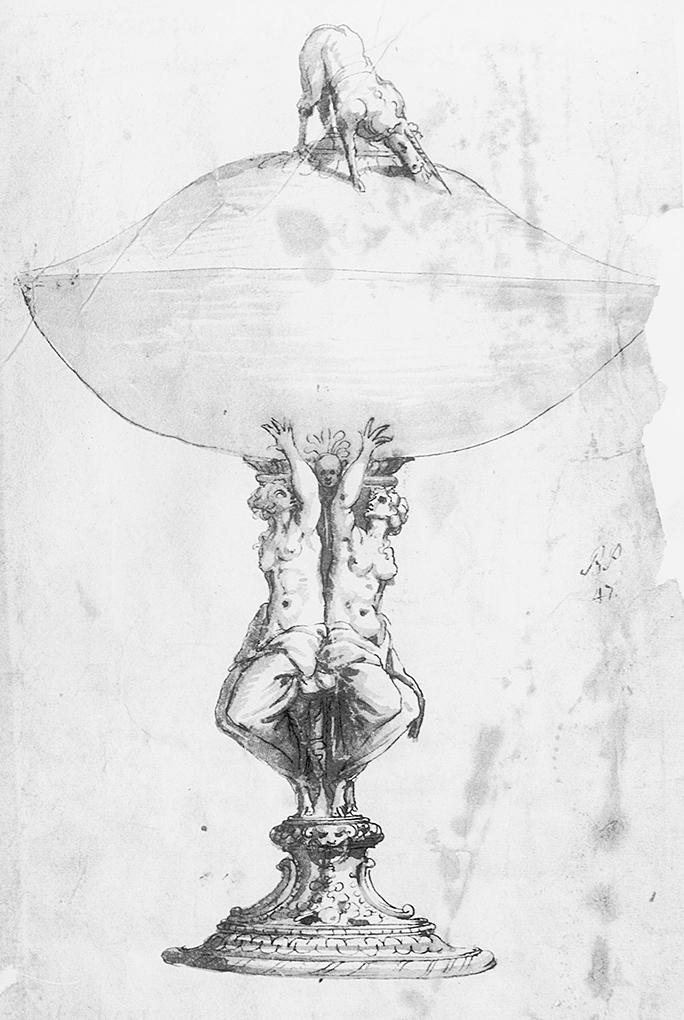

Fig. 3: Drawing of a Chalice attributed to Francesco Salviati, ca. 1530’s (left; Louvre, inv. RE 53024 verso); detail of a Farnese Candlestick by Antonio Gentili da Faenza, 1578-81 (right; Treasury of St. Peter’s Basilica, Vatican City)

Another apparent influence on Antonio is the work of Perino del Vaga, who was already an esteemed draughtsman recruited regularly for his inventive disegni in the area of decorative arts during Antonio’s early activity as a goldsmith. Beatriz Chadour has called attention to Perino’s influence on Antonio, distinguished by corollaries featured in Perino’s visual repertoire in the apartments of Pope Paul III at the Castel Sant’Angelo in Rome and the Sala Regia in the Apostolic Palace of Vatican City.18 Perino also furnished the designs for the rock crystals cut by Giovanni Bernardi de Castelbolognese that were destined for the Farnese Casket and those later inherited for incorporation on Antonio’s Farnese Altar Service.19

Guglielmo della Porta, likewise had an influence on Antonio, evident by Antonio’s earliest documented commission—the previously noted twelve silver reliquaries made for Pius V—which were based on designs provided by Guglielmo (no. 14).20 Antonio’s operation alongside other sculptors and metal-workers also collaborating with Guglielmo—like Sbarri, Baldo Vazzano da Cortona, Bastiano Torrigiani and Jacobus Cornelis Cobaert—provide further examples of Antonio’s operation in-and-around Guglielmo’s orbit.

Antonio’s employ of a crucifix for the Farnese Altar Cross, whose sculpted model had been executed by Guglielmo, is additional evidence for the working relationship between Antonio’s workshop and that of Guglielmo’s during the 1570s.21 Further evidence of this relationship is exemplified by other productions involving Antonio’s incorporation and reproduction of Guglielmo’s models into works cast and finished by Antonio and his workshop (see nos. 7-11). Most importantly, the crucifix featured on the Farnese Altar Service allows for a comparison between Guglielmo’s original invention and its interpretive treatment by Antonio who subdues, even oppresses the free and energetic manner of Guglielmo’s models, opting for a simplified and polished approach that we may presume further signifies Antonio’s predilection toward a conservative style (fig. 17).22 Nonetheless, the impact of Guglielmo’s creative impetus is still evident in Antonio’s occasionally adventurous interplay of Mannerist elegance meets overstated pomp expressed by his uniquely articulated masks, caryatids and bursting cornucopias of figs (fig. 4).23

Fig. 4: Drawings of Vases with Caryatids attributed to Guglielmo della Porta (left; private collection; center, Victoria & Albert Museum, inv. 9253); drawing of a Candlestick attributed to Guglielmo della Porta (right, Pierpont Morgan Libray, inv. I, 33, detail of the recto)

During the initial decades of activity in which Antonio established himself in Rome, we can envision him diligently producing and refining workshop models, several of which would reprise themselves in various incarnations throughout his identifiable body-of-work. While some scholars have suggested Antonio was only a metal caster,24 his identification as an “excellent sculptor” by Giovanni Baglione25 and the contemporaneous reference as having “sculpsit” his relief of the Skills of a Prince, leads to a confident conclusion that he excelled in sculpture as well, a notion first forwarded by Werner Gramberg.26

In addition to producing his own models there is documentation regarding Antonio’s procurement and possession of models from other sculptors and tradesmen during the course of his career, a practice typical of the goldsmith trade during this era. Antonio commented on owning plasters and moulds of models by many “worthy sculptors” including Michelangelo.27 Indeed, Michelangelo was not averse to giving his models away as he saw fit, perhaps even with the tacit hope specialists in metalwork might preserve them.28 Antonio’s employ of Guglielmo’s crucifix for the Farnese Altar Cross is one example already cited, however, a Pietà model or relief depicting the “expired Christ in the arms of the Virgin”29 by Antonio’s friend, Jacobus Cornelis Cobaert, was also possibly in his workshop.30 The composition was likewise based on a design by Guglielmo and enjoyed a widespread diffusion31 indebted to contemporary castings executed by more than a single workshop,32 and suggesting Antonio could have been responsible for some possible casts of the relief. Indeed, the Medici Archives cite a framed relief in silver that Antonio made of the “Passion of Christ with the Most Holy Madonna,” on 19 February 1585 (no. 34).33

A series of reliefs depicting Ovid’s Metamorphosis—also executed by Cobaert and based on Guglielmo’s designs—were similarly diffused among goldsmiths and sculptors.34 Bronze casts of these reliefs are found in various public and private collections and a series made in gold repoussé were realized by another goldsmith in Guglielmo’s circle: Cesare Targone, which had formerly been erroneously attributed to Antonio.35 Two silver casts from the series, depicting Jupiter Striking the Giants and the Battle of Perseus and Phineus at the Vatican Museums are executed with such fidelity, refinement and finishing as to possibly be silver casts made in Antonio’s workshop, although both are set in later, presumably late 19th or early 20th century settings (fig. 5).36 For a period, Antonio was in possession of the original clay models of the Metamorphosis reliefs made by Cobaert, having received them from Bastiano Torrigiani.37 Antonio and Torrigiani shared an earnest friendship, evident in their business transactions and attested in Baldo Vazzano’s personal account of their amity, in addition to Antonio’s company the night before Torrigiani’s death.38

Fig. 5: Silver relief of the Battle of Perseus and Phineus, possibly cast by Antonio Gentili da Faenza, from a model by Jacob Cornelis Cobaert, ca. 1550-60, after a design by Guglielmo della Porta, mounted in a later 19th or 20th century setting (Vatican Museums, inv. 65505)

In 1586 Antonio had purchased from Phidias della Porta, Guglielmo’s eldest son, a wax model of Mount Calvary, unwitting that Phidias had stolen the model illicitly from his father’s estate. The model was subsequently purchased back from Antonio by Guglielmo’s legal heir of the artwork, Teodoro della Porta, in 1589.39 Several casts of the Mount Calvary are likely indebted to Antonio’s production (see nos. 7-9).

By 1563 Antonio had successfully established himself as a prominent goldsmith and was elected as one of four appointed Consuls among the Confraternity of Goldsmiths in Rome. The confraternity would meet at the guild’s church, Sant’Eligio degli Orefici, attending Feast Days and Sundays and reinforcing Antonio’s presumed penchant for tradition (fig. 6).40 It is to be speculated if Antonio’s election on the Consul in this year may have been influenced by the confraternity’s efforts to seek Papal backing against those unlawfully in possession of their archives and property. In this same year a decree was also issued limiting the appraisal of gold and silverwork beyond the value of one scudo, a ruling certainly involving Antonio’s influence, as it was enacted only a month after his election to the Consul.41 Other decrees occurring during Antonio’s tenure involved penalties for opening a shop without a license from the Consuls and a prohibition toward the use of glass doubled with a thin stratum of precious stones. This latter decree being in-keeping with the high standards we can observe already in Antonio’s regard for quality workmanship.

Fig. 6: Sant’Eligio degli Orefici, Rome

The location of Antonio’s workshop along via del Pellegrino is identified in a document of 156542 and in 1567 he purchased an additional warehouse in the Trastevere area for 500 scudi, about a twenty-minute walk from his main workshop. This latter purchase demonstrates the prosperity of his business during this period. Soon thereafter, in 1569-70, Antonio was elected Chamberlain of the Confraternity of Goldsmiths as its leading steward.43 Antonio’s role and influence among the goldsmiths of Rome during this period can be observed in a deed drafted and witnessed in his workshop on 12 March 1572 concerning business on behalf of several silversmiths, for example.44

In 1570, Antonio’s participation with the Brescian painter, Girolamo Muziano, and the Roman illuminator, Lorenzo de Rosolis, resulted in the collaborative realization of a series of 130 copper engravings depicting reliefs from the Trajan column in Rome (fig. 7),45 later published as Historia utriusque belli Dacici a Traiano Caesare gesti: ex simulachris quae in columna eiusdem Romae visuntur collecta, and dedicated to King Philip II of Spain. We know the effort took no more than six years to complete as the first edition was printed in 1576 by Francesco Zanettei and Bartolomeo Tosi as well as by Bonifacio Breggi. A further edition was published in 1585 by Paulo Graziano and a final edition was printed in 1616 by Giacomo Mascardi.46

Fig. 7: Engraved print (pl. 25) from the 1576 edition of Historia vtriusque belli Dacici a Traiano Caesare gesti printed by Bonifacio Breggi (Emory University)

Regrettably, Antonio’s specific role in this project is unknown. It seems Muziano was the one granted unique license to organize the publishing of the prints of Trajan’s friezes and may not have been involved in all or any of the draftsmanship, to which he is often credited,47 but was presumably delegated to Lorenzo or others. By 1578 we may observe, for example, Muziano’s appointment by Pope Gregory XIII to exclusively preside over all Vatican commissions,48 and thus this managerial role in the project seems more likely than the notion of an aggressive solo production of 130 drawings with more than 2,500 figures depicted. It is also generally believed the plates reproducing the friezes were possibly born from earlier drawings by Jacopo Ripanda who was first to produce complete sketches of the column while being suspended from its peak.49

We might assume Antonio’s role in the project may have been similar to Muziano’s, serving as an organizer to contract the execution of the plates by several engravers and possibly inclusive also of his own participation. This magnanimous responsibility precludes later multifaceted managerial tasks like his oversight on the completion of the Altar of the Holy Sacrament at the Basilica di San Giovanni in Laterano in subsequent decades.50 Antonio’s role as Chamberlain to the Confraternity of Goldsmiths in this year (1570) would have placed him in the unique position to have access to Rome’s engravers, notwithstanding his possible provision and preparation of the prepared copper plates required for the ambitious project.

We can assume Antonio had skills as an engraver since the chasing of metal in the practice of goldsmithing is related. The high-quality engravings featured on the interior plates for the binding of the Farnese Hours that Antonio produced (no. 3), if not executed by one or more assistants, is of a superior quality and could be indicative of Antonio’s talent as an engraver (fig. 8). In spite of Antonio’s close proximity with the Trajan column project, the iconographic program depicted on the column doesn’t seem to have had much influence on him in respect to style or composition.

Fig. 8: Detail of the engraved interior back cover binding for the Farnese Hours, depicting the heraldic escutcheon of Odoardo Farnese by Antonio Gentili da Faenza, ca. 1589-94 (Pierpont Morgan Library, NY, inv. MS.69)

A group of five engravings forming a large format reproduction of the Farnese Altar Service is logically considered an engraving made by Antonio,51 as adjudged by its annotated inscription which notes its personal authorship by Antonio and likewise commemorates Cardinal Alessandro Farnese who, by this time, had already passed away (fig. 9).52 As the Altar Service was already in St. Peter’s, Antonio appears to have relied upon his sketches of the project to formulate the engraving, as accounted for by the differences observed between the print and the finished work.53 Only four examples of the print are known: two in Paris,54 one in Brüssels55 and another in Vienna.56 There is an additional engraving of a chalice at the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris, glued to one of the prints for the Altar Service, which, according to Chadour, can be favorably linked to Antonio’s authorship.57

Fig. 9: A collection of assembled engraved sheets depicting the Farnese Altar Cross, attributed to Antonio Gentili da Faenza, ca. 1589-96 (Museum für angewandte Kunst, inv. KI7413)

Antonio’s talents seem to have extended beyond his technical powers and into the realm of design as Baglione praised Antonio’s skill in drawing and his execution of designs for fountains.58 A mid-16th century fountain in the Lazio Viterbo Ronciglione Piazza del Duomo, the summer palace of Cardinal Alessandro Farnese, is attributed to Antonio, not only on account of its visual language, incorporating unicorns and low-relief masks, but also due to its probable commission by Alessandro who was Antonio’s regular patron (fig. 10).59 While it is unlikely Antonio had any involvement in carving the stone fountain, he may have had some role in the preparation and execution of its bronze elements. His experience in managing the production of a work-in-stone may be reprised later, when in 1601 he was procured to jointly oversee the execution of two marble prophets sculpted as decorative embellishments for the organ at Santo Giovanni Laterno, executed by two stone sculptors.60

Fig. 10: Detail of a fountain in the Lazio Viterbo Ronciglione Piazza del Duomo, whose design is attributed to Antonio Gentili da Faenza, ca. 1553-65

The Ronciglione fountain is thought to have been realized sometime between 1553-65 and would place it within the period for which there are no known sources concerning Antonio’s activity.61 At least one of his tableware productions, an elaborate ewer for the Medici, to be discussed, was executed “in the style of a fountain,”62 and could infer Baglione’s claim in realizing such designs (no. 19). The technical virtuosity involved in conceiving the ewer is tantamount to a brilliant mind capable of producing equally elaborate outdoor fountains. While several drawings have been associated with Antonio’s hand, though none reproducing designs for fountains, the authorship of drawings associated with him is debated and his sketched oeuvre remains largely ambiguous but worthy of future research.

Although speculative, Antonio could have had involvement in the preparatory designs for fountains in-and-around Rome, namely those involving Antonio’s patron, Muzio Mattei, who financed his own independently sponsored fountains as well as those commissioned by Antonio’s other patron, Pope Sixtus V, for whom Mattei oversaw the realization of fountains like the Quattro Fontane at the juncture of via delle Quattro Fontane and via del Quirinale in Rome.63 The Roman architect, Domenico Fontana, was also involved in the realization of the Quattro Fontane and in 1590 both Fontana and Antonio are observed working together on behalf of Sixtus V in overseeing the final work for the production of the tabernacle at Sta Maria Maggiore.64 Fontana and Antonio’s mutual activity in Naples later in their careers may also suggest a possible collaboration in the production of fountains in that city during the late 16th and very early 17th century.65 We might consider the Pope’s assignment to Fontana concerning the restorations he ordered for Trajan’s column during the mid-1580’s could have drawn these two artists together in consideration of Antonio’s previous participation in the preparation of the plates reproducing the column’s scenes. Antonio’s close friend, Torrigiani, whose workshop executed the large statue of St. Peter for the top of the Trajan column, may have again brought Fontana into Antonio’s orbit. The otherwise ambiguous intersection and association of these various artists and patrons may suggest Antonio’s otherwise undocumented participation in the fountain designs for which Baglione praises him.

In 1575 Antonio was elected third Consul of the Fraternity of Goldsmiths and in this same year Sixtus V reconfirmed the privilege of the confraternity to remain exempt from paying shop and street taxes while the acting Pope, Gregory XIII, granted a new title to the confraternity, naming it the Collegio e Nobil Arte, and placing it under the control of the Camera Apostolica. Antonio’s evidently good standing with these individuals would in all likelihood lead to his future appointment as Assayer of the Papal Mint in 1584.

In May of 1576, Antonio rented an additional property along via del Pellegrino for a period of five years at an annual rate of 50 scudi. It could be presumed that this rented property, already close to his established workshop along the same street, was leased in association with the advent of a company he established that year with the goldsmiths Orazio Marchesi, with whom he is noted as having earlier collaborated, and a certain Gabriele Berardi.66 It is possible Antonio, at approximately fifty-seven years-of-age, and with presumably increasing workloads—evident in the various projects he executed for the Medici during this period—sought to establish a broader company to increase profits, pool debts or to focus his personal attention on works of anticipated greater importance like the Farnese Altar Service, delegating lesser tasks to steadily contracted assistants. Only a year later, Antonio would dissolve this formal partnership with Marchesi and Berardi and adopt another goldsmith into his fold: Carlo Boni from Faenza.

It could be speculated that Antonio’s turnover of these goldsmiths could be on account of the tradition among the confraternity in hosting and aiding incoming gold-and-silversmiths from outside of Rome until they established themselves.67 This is potentially the case with Gabriele Berardi who may have originally been active as a silversmith in Palermo in Southern Italy and originally a native of Majorca, off-the-coast of Spain.68 The Berardi were a noble family of Jewish converts living in Southern Italy and we might assume, if arriving in Rome for work, would have been resident in the Jewish community within Rome where one of Antonio’s Catholic clients, Duke Muzio Mattei,69 also happened to live.70 We could assume Berardi had already completed work for Mattei and came to Antonio by way of Mattei’s recommendation or that Antonio may have met Berardi while working for Mattei in the Jewish subdivision of Rome.

It could also be assumed Carlo Boni da Faenza might also have partnered with Antonio for this same reason but he appears already present in Rome as part of the Confraternity of Goldsmiths as early as 1570. Also present in Rome are other goldsmiths from Faenza, such as: a certain Alessandro Bernardi71 and an Andrea de Monte,72 both of whom were possibly attracted to Rome on account of Antonio’s success.

While little is known of Orazio Marchesi, it would seem he was a trusted collaborator of Antonio’s. It’s possible he was either the son or a relative of the Brescian goldsmith, Panfilo Marchesi, who was active in Rome during the 1550s and appears to have been well-connected. For example, the accomplished sculptor, Vincenzo Danti—responsible for the bronze statue of Pope Julius III situated outside the Duomo di Perugia—lived and worked in Panfilo’s workshop in Rome during the mid-1550s.73

In Antonio’s documented service to the Medici, under the auspices of Francesco I de’ Medici—Grand Duke of Tuscany from 1576-85—we can gather perspective on requests made between patron and goldsmith. In one instance Antonio is called upon to clean and refresh a work he had earlier created (no. 19) and in another instance he is called upon to update a devotional treasure (no. 25). These otherwise banal tasks offer insight into the simpler responsibility’s goldsmiths experienced in their trade, being a divergence from the elaborate masterworks for which they are most celebrated.

For the Medici, Antonio realizes a variety of objects to include utilitarian luxury items like ewers, platters, tableware, jars, caskets and an oil lamp and devotional items like reliquary crosses, a chrismatory and a tabernacle. Some requests are for the Medici themselves while others are intended as gifts, forming part of the cultural milieu of the period, notwithstanding the employ of gifts as part-and-parcel in matters of diplomacy and status.74

Antonio’s earliest dated work for the Medici involved the creation of a tall silver ewer featuring harpies and masks of naiads in low-relief with two cartouche-style handles (no. 19). This elaborate ewer had three mouths for individually pouring water and two kinds of wine while the interior featured a fourth central compartment to store ice. The lid of the ewer featured vines in-relief surmounted by a jar bursting with fruits.75 A sketch of a vase at the Rijksmuseum, associated with Antonio, might be indicative of the type of visual language described for the ewer, and if representing a work executed by Antonio, could date it to a period in which he was producing alike objects for the Medici during the late 1570s (fig. 11). The location and fate of the ewer is unfortunately lost; however, it was originally destined for the Medici Guardaroba in Florence but appears to have remained in Rome.76

Fig. 11: Drawing of a Decorative Vase with Fruits, attributed to Antonio Gentili da Faenza, probably late 1570s (Rijksmuseum, inv. RP-T-1956-113)

Antonio may have contributed to the preservation and display of precious antiquities kept among the Medici possessions in Florence. For example, a gold setting was realized by Antonio for a small agate cup that may have been of Classical origin (no. 23).77 Antonio’s setting for a turquoise-glass paste bust of Emperor Augustus is certainly indicative of Antonio’s role in enhancing the Medici ducal collection at-this-time (no. 2).

By 28 September 1583, Antonio had executed for the Medici, a gilt silver and ornamented frame for a portrait of the Madonna painted by Scipione Pulzone (called Il Gaetano) (no. 29).78 Notably, a signed and dated portrait of the Madonna, by Il Gaetano, from 1583 survives (fig. 12).79 The painting is a small devotional work, approximately 35 x 25.4 cm, befitting for the precious frame described as approximately one-half a braccia or a half-arm’s length in the Medici inventory. A later 1627 posthumous inventory of Cardinal Francesco Maria del Monte cites two Madonna panels also by Il Gaetano: a larger example in an ebony frame and a smaller example, commensurate with the surviving painting, described with a golden frame, and presumably that of Antonio’s invention, now lost.80

Fig. 12: Painting of the Madonna by Scipione Pulzone, called Il Gaetano, 1583 (private collection)

Of note are the various items the Medici commissioned from Antonio to be used as gifts. On 12 April 1584 two works contracted to Antonio: a golden quill pen and a small gilt silver beaker or jar with a lid and narrow mouth; was presumably a writing set destined for the studiolo of Francesco I’s daughter: Eleanor de’ Medici (no. 31).81 The set was likely intended as a gift in celebration of her marriage to Vincenzo I Gonzaga which took place later that month on 29 April 1584.

The Medici also commissioned Antonio to produce works destined for the Hapsburg court of Spain, namely Philip II, for whom Antonio made a silver chrismatory (no. 33). An armorial, presumably of the Spanish crown, was applied to it and the object was sent to Philip II as a gift for the reliquaries of San Lorenzo in the treasury of the Cathedral of Seville on 31 December 1584.82 Additionally, two golden crosses made by Antonio—with relics set behind rock crystal windows—were both sent to Spain as gifts in October of 1581 and February of 1583 respectively (nos. 24, 26).83 An awareness of Antonio’s skill and talent was evidently recognized by the court of Philip II, as his daughter, Catalina Micaela, would later commission Antonio to produce a silver plaque of the Skills of a Prince as a gift for the Doge of Venice, a new discovery published in this catalog for the first time (no. 4). Further, the inscribed base of a pax attributed to Antonio and a cast of the Mount Calvary relief that may have been commissioned by Philip II and subsequently donated to the Monastery of El Escorial, are suggestive of the dissemination of Antonio’s productions into Spain (nos. 7 and 12).

On 7 April 1584, at approximately sixty-five years-of-age, Antonio received the title of Assayer of the Papal Mint, an appointment he would fulfill for eighteen years. Antonio’s service in this capacity is found in his involvement in the final statement of work for the Sta Maria Maggiore tabernacle in Rome in 1590, executed by Bastiano Torrigiani and Ludovico del Duca;84 his appraisal of a gilt copper armorial at Castel Sant’Angelo, executed by Bernardo Salvioni for Clement VIII in 1596;85 and his oversight in the production of the cast metal components for the Altar of the Holy Sacrament at the Basilica di San Giovanni in Laterano executed by Pompeo Targone and Curzio Vanni.86 In the latter effort Antonio organized as many as twenty-three individual specialists in the execution of the altar, indicative of his immense responsibility, respect and vast network.87 Antonio subsequently presided over another work in that location: the two marble prophets for the organ made by Mastro Ambrosio from Milan and Fra Lalbino in August of 1601, already noted, and after his tenure, Antonio would continue serving as an occasional consultant in such matters, evident by his involvement in overseeing a reliquary executed by the silversmith, Carlo Minotto, for the Marquis of Vigliena in Sicily in October of 1607.88

During his tenure as Assayer of the Papal Mint, Antonio, in 1586, rented a house from Tommaso Castellani along via Giulia which would later become Antonio’s new workshop. In 1588 the silversmith, Baldo Vazzano da Cortona, was resident in Antonio’s workshop, having arrived in Rome in 1582 and learning the art of smelting alongside Bastiano Torrigiani and training thereafter under the auspices of the silversmith, Pietro da Prato.89 Vazzano would continue to work with Antonio as late as 1605.90

In March of 1588, Antonio’s service to the Medici dynasty was tangentially reprised when Francesco de’ Medici’s younger brother, Ferdinando de’ Medici—by then, the new Duke of Tuscany—in preparing a purchase of horses and silver from the estate of Cardinal Jacopo Savelli in Rome, appointed Antonio to evaluate the works of silver and gold being purchased.91

Antonio and his son, Pietro, must have spent a significant part of their career between Rome and Naples from 1593 to 1603 while the production of the cross for the Monastery of San Martino occupied their attention (no. 37).92 This large cross, around 7 feet tall, featured forty-two figures, numerous reliefs and weighed over a hundred pounds.93 Antonio’s delegation of the casting for his Skills of a Prince relief in January 1597, to the silversmith Cristoforo Vischer, may have been due to Antonio’s presence in Naples during the looming deadline for its final production.

Antonio may have initially begun collaborating with Vischer in Naples around 1594-95. Vischer was a silversmith from Augsburg, Germany who appears to have had associations with Naples and his brother, Giorgio Vischer, also a silversmith, was certainly in Naples during this period.94 It could be presumed the Vischer brothers served as assistants to Antonio while working on the San Martino cross. Cristoforo Vischer may have followed Antonio to Rome after completion of the cross, as he appears registered among Rome’s goldsmiths in 1604, just following the year in which the San Martino cross was completed. Vischer later established his own workshop in Rome along the same street as Antonio’s during the 1610’s. Apart from the Skills of a Prince cast by Vischer, only one additional known work bearing Vischer’s hallmark is identified on a pax from about 1617-25, belonging to a church within the Diocese of Adria-Rovigo and featuring a Pietà relief whose frame is attributed in this catalog to Antonio’s invention (nos. 12, 13; fig. 31), and further reinforcing the theoretical working relationship shared between Vischer and Antonio.

In 1599 Antonio purchased Torrigiani’s former property along Borgo Pio, which may have served briefly as a foundry for a few years, until he shortly thereafter sold it back to Torrigiani’s son in 1601.95

In an attempt to possibly preserve his family legacy, Antonio may have been instrumental in establishing his son, Pietro, as Assayer of the Papal Mint in 1602. During the first part of 1609 Antonio would be summoned to testify in an inconclusive case involving the unsanctioned use of models from Guglielmo della Porta’s studio, the testimonies of which, provide ample insight into the interconnectedness of goldsmiths in Rome during this period. For example, at this late date, Antonio appears to have relied on a formatore other than Vazzano, who was, by this year, working elsewhere and instead employed Sebastiano Marchini to produce wax models derived from a plaster form belonging to Antonio’s workshop (no. 40).96 Later that year, on 29 October 1609, Antonio died at the age of 89 or 90. He was buried at the church of St. Biago along via Giulia in Rome.

For Antonio we may gather the picture of a goldsmith who not only excelled in his trade, fittingly performing an art in-keeping with the conventions of his time, but also excelling by his aptitude for problem-solving, where feats of engineering were coupled with a visually sublime elegance. It was Antonio’s ability to produce sophisticated works-of-art in a timely and accomplished manner that afforded the respect of patrons both noble and religious, heralding him as an artist in his trade “to which there was no rival,” as proclaimed by Baglione.97 In all, it is his attention to all of these details that award Antonio as one of the most important Italian goldsmiths of late 16th century Rome. His creations would later enjoy their own renaissance during the late 18th century when the English sculptor, John Flaxman, in 1770, ordered and acquired plaster casts of the figures featured along the base of the Farnese Altar Cross from Rome, at-that-time, superficially thought to be models by Michelangelo. The models would find their way into the studios of Josiah Wedgwood and the clock-maker Matthew Boulton who both subsequently reprised Antonio’s models on their own unique inventions (fig. 13).98

Fig. 13: Black basalt Michelangelo Lamp by Josiah Wedgewood and factory, after a design introduced about 1772, this example possibly 19th century, with figures after the Farnese Altar Cross (Victoria & Albert Museum, inv. 4790&A-1901)

Endnotes:

1 Carlo Grigioni (1988): Antonio Gentili detto Antonio da Faenza in Romagna arte e storia, XXIV, pp. 83-118.

2 Sidney J. A. Churchill (1907): The Goldsmiths of Rome under the Papal Authority: Their Statutes Hitherto Discovered and a Bibliography in Papers of the British School at Rome, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 163–226.

3 Various authors (1964): Le Muse: enciclopedia di tutte le arti. Novara, Instituto Geografico de Agostini, vol. V, p. 203.

4 This dispute takes place in June of 1553. C. Grigioni (1988): op. cit. (note 1).

5 Salvatore Fornari (1968): Gli argenti Romani. Rome, p. 76.

6 Carlo Celano (1758): Notizie Del Bello, Dell’antico e del Curioso della Citta di Napoli. Naples, p. 31.

7 Antonio and Pietro Gentili’s collaboration on works for Federico Borromeo are inferred in a letter Pietro sent to the Cardinal on 5 November 1616 in which he refers to past commissions the father-and-son team executed for him. C.D. Dickerson (2006): Bernini and Before: Modeled Sculpture in Rome, ca. 1600-25, PhD. thesis, Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, p. 396.

8 Regrettably, the core of Pietro’s commissions is lost with exception of an elegant silver reliquary bust of Saint Bibiana, executed between 1609-10, preserved in the Basilica Papale di Santa Maria Maggiore. The reliquary was commissioned by the canon, Girolamo Manlili, for which Pietro was paid a sum of 223 scudi. S. Fornari (1968): op. cit. (note 5). However, C.D. Dickerson has suggested the reliquary present in the Basilica may be an 18th or 19th century work. C.D. Dickerson (2006): op. cit. (note 7), pp. 404-05.

9 The earliest document concerning Antonio’s role as a goldsmith is dated, 18 December 1552. C. Grigioni: (1988): op. cit. (note 1).

10 Werner Gramberg (1960): Guglielmo della Porta, Coppe Fiamingo und Antonio Gentili da Faenza in Jahrbuch der Hamburger Kunstsammlungen, V, pp. 31-52.

11 For Duke Mattei’s commissioning of Antonio see Minna Heimbürger Ravalli (1977): Architettura scultura e arti minori nel barocco italiano: Ricerche nell’archivio. Spada. Florence, p. 85. Documents concerning Antonio’s work for the Medici are preserved in the Medici Archives in Florence, chiefly in Guardaroba, filza 79. Invetarij Generale a Casi A. 1571-1588 and elsewhere.

12 Anna Beatriz Chadour (1982): Der Altarsatz des Antonio Gentili in St. Peter zu Rom in Wallraf-Richartz-Jahrbuch, vol. 43.

13 Christina Riebesell (1995): La Cassetta Farnese in I Farnese: Arte e Collezionnismo. Milan, pp. 58-69.

14 John Forrest Hayward (1977): Roman Drawings for Goldsmiths’ Work in the Victoria and Albert Museum in The Burlington Magazine, vol. 119, no. 891, pp. 412-21; Gianvittorio Dillon (1989): Novità su F. Salviati disegnatore per orafi in Antichità viva, XXVIII, 2-3, p. 48; and Catherine Monbeig Goguel (1998): Il disegno in Francesco Salviati in Francesco Salviati, 1510-1563, o la Bella Maniera. Electa, Milan, pp. 31-46.

15 Antonino Bertolotti (1881): Artisti lombardi a Rome nei secoli XV, XVI, XVII. Studi e ricerche negli archivi romani, 2 vols., Milan, vol. I, p. 129.

16 The sheet is kept in the Pierpont Morgan Library drawings collection (inv. 1964.3). Another sheet by Salviati, depicting a desk casket, at the Uffizi, is also comparable (inv. 1577E).

17 Cherubino Alberti’s plates were either refreshed or reengraved in another edition of this print executed by Aegidius Sadeler II in 1605. Anna Beatriz Chadour (1980): Antonio Gentili Und Der Atarsatz von St. Peter. Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität, PhD. thesis, pp. 182-83.

18 Ibid.

19 Giorgio Vasari (1568): Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors and Architects. Translated by Gaston Du C. De Vere. Macmillian, London (1913), vol. VI, pp. 76-78.

20 W. Gramberg (1960): op. cit. (note 10), pp. 31-52.

21 Michael Riddick (2017): Reconstituting a Crucifix by Guglielmo della Porta and his Colleagues. Renbronze.com (accessed June 2022).

22 Ibid.

23 Both sheets feature early attributions to Giovanni da Udine, inscribed thereon and discounted by modern scholarship. Peter Ward-Jackson and Elena Parma have suggested the Victoria & Albert sheet belongs to the hand of Perino del Vaga: Peter Ward-Jackson (1979): Italian Drawings: 14th-16th century. Victoria & Albert Museum, London and Elena Parma (2001): Perino del Vaga, tra Raffaello e Michelangelo, ex. cat., Galleria civica di Palazzo Te. However, Parma earlier followed the original attribution to Guglielmo della Porta in E. Parma (1986): Perin del Vaga, l’anello mancante. Genoa. The proposal of these sheets and their attribution to Guglielmo is first proposed by Bernice Davidson in Bernice Davidson (1966): Perino del Vaga a la sua cerchia (ex. cat., Florence). This assessment is currently endorsed by Linda Wolk-Simon in Linda Wolk-Simon (2003): Reviewed works: Perino del Vaga, tra Raffaello e Michelangelo in Master Drawings, vol. 41, no. 1, pp. 44-58 and also by Florian Härb in Florian Härb (2001): Review of exhibition Perino tra Raffaello e Michelangelo, Mantua in Burlington Magazine, 143, no 1183, pp. 652-54.

24 Rosario Coppel (2012): Guglielmo della Porta in Rome in Guglielmo della Porta: A Counter-Reformation Sculptor. Coll & Cortes, p. 56.

25 Giovanni Baglione (1642): Le vite de’ pittori scultori et architetti. Dal pontificato di Gregorio XIII del 1572. In fino a’ tempi di Papa Vrbano Ottauo nel 1642. (…e modellava da sculture Eccelentemente…)

26 W. Gramberg (1960): op. cit. (note 10), pp. 31, 33, 38 and 48.

27 A court record of 1609 records Antonio’s comment: “In bott ega mia io…ho bene li molto gessi et forme di molti valenti homini e di Michelangelo et d’alteri, che saria longo a raccontare.” or ”In my workshop…I have had many plasters and moulds by many worthy men and of Michelangelo and of others.” A. Bertolotti (1881): op. cit. (note 15), vol. 2, pp. 136-37.

28 Victoria Avery (2018): Divine Pipe Dreams: Mature Michelangelo and the mastery of metal in Michelangelo: Sculptor in Bronze. Bloomsbury Publishing, UK, pp. 80-105 and Michael Riddick (2020): The Thief of Michelangelo. Models Preserved in Bronze and Terracotta. Renbronze.com (accessed June 2022).

29 G. Baglione (1642): op. cit. (note 25), pp. 100-01. “Formo ancora altri modelli di cose sacre, e tra le altre un Christo morto in braccio alla Vergine Madre, affai bello.”

30 A witness, Johannes Baptista Montani Mediolanensis, at the 1609 trial concerning the contested use of models belonging to Teodoro della Porta, describes seeing a Pietà and/or a Descent from the Cross in Antonio’s possession: “Io di queste robe ho visto in mano di Mº. Antonio da Faenza una pietà o Cristo in Croce cosa bellísima che era di cera longa più di una canna che vedendo io quella bella cosa mi disse che quella opera andava in S. Pietro…” or “Among these things I have seen in the hand of Master Antonio da Faenza a most beautiful Pieta or Christ on the Cross made of wax, of more than one caña in length, and when I saw that beautiful object, he told me that the piece was in St. Peter’s.” A. Bertolotti (1881): op. cit. (note 15). It is possible this was a Descent from the Cross forming a group of eight individual scenes of the Passion of Christ that were displayed at St. Peter’s in 1564. Charles Avery (2012): Guglielmo della Porta’s Relationship with Michelangelo in Guglielmo della Porta, A Counter-Reformation Sculptor. Coll & Cortés, pp. 113-137. Antonio was quite likely in possession of a model of the Pietà executed by Cobaert after Guglielmo’s design. It is likely he cast an example of this Pietà for the Medici in 1585 (see no. 34 in the present catalog).

31 Ulrich Middeldorf commented that this composition was the most popular devotional image around the year 1600. Ulrich Middeldorf (1944): Medals and Plaquettes from the Sigmund Morgenroth Collection. Donnelley & Sons Co., Chicago, IL., no. 186, p. 28. For further analysis of this composition and its diffusion see Michael Riddick (2017): A Renowned Pieta by Jacob Cornelis Cobaert. Renbronze.com (accessed June 2022).

32 For example, we know another Roman sculptor and bronze founder, Bastiano Torrigiani, also cast one or more examples of this composition as an unpublished archive cites him having cast a Pietà made by Cobaert for the collector Simonetto Anastagi in 1585. Emmanuel Lamouche (2011): L’activité de Bastiano Torrigiani sous le pontificat de Grégoire XIII. “Dalla gran scuola di Guglielmo Della Porta.” in Revue de l’art, no. 173, pp. 51-58 (see his footnote 54).

33 Medici Archivio, Guardaroba, filza 79. Invetarij Generale a Casi A. 1571-1588, fol. 373r.

34 G. Baglione (1642): op. cit. (note 25), p. 100 and A. Bertolotti (1881): op. cit. (note 15), vol. 2, pp. 140-43.

35 Davide Gasparotto (2014): The power of invention: Goldsmiths and Disegno in the Renaissance in Donatello, Michelangelo, Cellini. Sculptor’s Drawings from Renaissance Italy. University of Chicago Press, pp. 40-55. See also Michael Riddick (2017): A Group of Gold Repoussé Reliefs attributable to Cesare Targone. Renbronze.com (accessed June 2022).

36 Vatican Museums invs. 65504-05. Werner Gramberg has alternatively suggested these may have been cast by Jacob Cornelis Cobaert. Gramberg (1960): op. cit. (note 10), pp. 47-48.

37 Antonio’s possession of the original models is noted in the 1609 trial. A. Bertolotti (1881): op. cit. (note 15).

38 Emmanuel Lamouche (2022): Les fondeurs de bronze dans la Rome des papes (1585-1630). École française de Rome, p. 87.

39 Antonio had purchased the Mount Calvary model from Phidias della Porta for 50 scudi, and was subsequently reimbursed when the model was purchased back by Teodoro della Porta by court order. A. Bertolotti (1881): op. cit. (note 15), vol. II, pp. 122, 154.

40 S. Churchill (1907): op. cit. (note 2).

41 Ibid. The decree is dated 29 July 1563 while the installment of new Consul members took place on the 25th of June.

42 Marina Cipriani (2000): Gentile, Antonio, detto Antonio da Faenza in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani – Volume 53. http://www.treccani.it (accessed August 2022).

43 Costantino G. Bulgari (1958): Argentieri, gemmari e orafi d’Italia, I, Roma, p. 509.

44 A. Bertolotti (1881): op. cit. (note 15), vol. 1, p. 325.

45 C. Grigioni (1988): op. cit. (note 1), p. 90.

46 Giovanni Agosti and Vincenczo Farinella (1985): Il fregio della colonna Traiana…, in Annali della Scuola normale superiore di Pisa, s. 3, XV, p. 1109. See also Tocino Fernández (2023): La Historia utriusque belli Dacici a Traiano Caesare gesti ex simulachris quae in columna eiusdem Romae uisuntur collecta de Alfonso Chacón. PhD. thesis, Universidad de Cádiz.

47 For recent analysis concerning the variety of drawings that relate to this project see Volker Heenes (2017): Zu den kopien der reliefs der Trajanssäule im 16. Jahrhundert: Zwei neue zeichnungen eines unbekannten rotulus in Columna Traiani – Trajanssäule – Siegesmonument und kriegsbericht in bildern. Verlag Holzhausen GmbH, pp. 271-78.

48 Patrizia Tosini (2012): Girolamo Muziano e Gregorio XIII: Una Rapporto Privilegiato in Unità e Frammenti di Modernità in Arte e Scienza nella Roma di Gregorio XIII Boncompagni (1572-1585). Fabrizio Serra Editore, 2012, pp. 278-97.

49 These sketches, the Codice Ripanda, are preserved in the Biblioteca dell’Istituto Nazionale di Archeologia e Storia dell’arte, Palazzo Venezia, Rome, ms. 254. Their attribution was designated to Jacopo Ripanda by Roberto Paribeni in 1929 but have more recently been challenged by Arnold Nesselrath. Roberto Paribeni (1929): La Colonna Traiana in un codice del Rinascimento in Rivista dell’Istituto di Archeologia e Storia dell’Arte 1, pp. 9-28 and Arnold Nesselrath (2010): XVI secolo, rilievo e fregio della Colonna Traiana in Le meraviglie di Roma antica e moderna, exh. cat. Rome, pp. 35-36.

50 E. Lammouche (2022): op. cit. (note 38), p. 183, see his footnote 160.

51 Wolfgang Lotz (1951): Antonio Gentili or Manno Sbarri? in The Art Bulletin, 33(4), pp. 260-262. and Andreas Andresen (1870): Handbuch für Kupferstichsammler. Leipzig, p. 563.

52 “Questo e il disegno della richissima croce d’argento nella quale vi sono di quatri ovati del posamento et i tondi delle teste de la croce sonno di cristallo intagliati con le istesse istorie che si vede. Et il piano de la croce e de lapis lazaro dell’istessa grandeza a punto che è l’opera con due candellieri simili, la quale dono a l’altare di Sa Pietro di Roma l’Illmo. Card. Farnese di felice me. vita sua nell’anno 1582” or “This is the design of the rich silver cross which has four ovals in the base and the tondos in the head of the cross in carved glass with the same stories on view. And the foot of the cross is in Lapis lazuli of the exact same size than the work with the two similar candle sticks, which he donated to the altar of Saint Peter in Rome the honorable Cardenal Farnese in loving memory in the year 1582.”

53 A.B. Chadour (1980): op. cit. (note 17), pp. 66-69.

54 Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, fol. Vb 108.

55 Bibliothèque Royale Albert, Brüssel Foto Nr. E 377.

56 Museum für angewandte Kunst, Inv KI7413.

57 A.B. Chadour (1980): op. cit. (note 17), p. 254 (see her footnote 267).

58 G. Baglione (1642): op. cit. (note 25).

59 Amico Ricci (1859): Storia dell’ architettura in Italia, dal secolo IV al XVIII, voI. III, Modena, p. 85.

60 Various Authors (1886): Deputazione di storia patria per le province di Romagna Bologina: Documenti e studi. vol. 1.

61 The dating of the fountain is based upon the respective years Cardinal Alessandro’s children passed away and whose armorials are featured on the fountain. A.B. Chadour (1980): op. cit. (note 17), pp. 177-79.

62 Medici Archivio (1571-88): op. cit. (note 33), fol. 9r. This entry is undated but probably dates from the late 1570s and describes the ewer appearing “like a fountain.”

63 Frederick Cope and Maurizia Tazartes (2004): Fontaines de Rome. Citadelles & Mazenod.

64 Jennifer Montagu (1996): Gold, Silver & Bronze: Metal Sculpture of the Roman Baroque. Princeton University, p. 20 and appendix 1. The records are located: ASV, Archivium Arcis, Arm. B, vol. 7, ff. 125-30v. In addition to Antonio Gentili, Domenico Fontana also signed-off on this statement-of-work.

65 For Domenico Fontana’s work on fountains in Naples see Ferdinando Ferrajoli (1973): Palazzi e fontane nelle piazze di Napoli. Naples, pp. 28-30.

66 A. Bertolotti (1881): op. cit. (note 15), vol. 1, p. 326.

67 S. Churchill (1907): op. cit. (note 2).

68 Gabriele Berardi could be the same namesake mentioned in the will of a certain Pere Tarongí (also called Perot and Perotto Torongi), a Jewish banker and businessman originally from Majorica, Spain, but living in Palmero, Italy who died there in 1539. In his will he granted money to a Gabriele Berardi, also a Jewish convert of Valencian descent. Gabriele’s brother, Galceran, had married Tarongí’s sister, Francina. Another of Tarongí’s sisters, Elionor, was married to a certain silversmith, Lluís de Vallseca, who was instrumental in various family dealings, having assisted in accounts of the business Galceran and Tarongí conducted together in Palermo and also serving as witness to Tarongí’s will and ensuring the succession of Galceran’s trust to his brother, Gabriele Berardi. There is some indication Galceran and Gabriele’s father, Joanot Berardi, was both a merchant and silversmith. Upon his death, Joanot’s mercantile efforts may have been passed to his son Galceran while his silversmith trade may have been passed to Gabriele. Gabriele may likewise have worked alongside or as an apprentice to Lluís who would have been his brother-in-law’s sister’s husband. As an occasionally persecuted minority, the Jewish community typically remained in well-knit circles. Pedro de Montaner Alonso (2010): Viejos y nuevos datos sobre los Tarongí y los Vallseca, judeoconversos mallorquines ennoblecidos en Sicilia in Memòries de la Reial Acadèmia Mallorquina d’Estudis Genealògics, Heràldics i Històrics Història, no. 20, Academia Asociada al Instituto de España, pp. 95-186.

69 M. Heimbürger Ravalli (1977): op. cit. (note 11).

70 At one time, by issue of the Pope, the Jewish community of Rome was ordered to be gated off although the Pope gave Duke Muzio Mattei a key to move in-and-out of the ghetto, as his palace was located therein. Anne Kristine Tagstad (2005): Fontana delle tartarughe, the iconography of a Roman fountain. PhD. thesis, University of Oslo, Norway.

71 Deputazione… (1886): op. cit. (note 60), p. 107.

72 Ibid., p. 207.

73 Ibid., pp. 104-07.

74 For a survey on the use of objects-of-virtue for personal, public and political use see Dora Thornton and Luke Syson (2001): Objects of Virtue: Art in Renaissance Italy. Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum and Lars Kjaer and Gustavs Strenga (2022): Gift-Giving and Materiality in Europe, 1300-1600: Gifts as Objects. Bloomsbury Publishing.

75 Medici Archivio (1571-88): op. cit. (note 33), see fols. 9v, 9r for the ewer and fol. 6v for its accompanying plain silver basin. The former completed by 7 August 1577 and the latter inventoried by 12 August 1577. Antonio Gentili “refreshes” the ewer in 1584 while executing an accompanying set of three platters and six pieces of tableware by 10 July 1584 (see fol. 407v).

76 Ibid.

77 Medici Archivio (1571-88): op. cit. (note 33), fol. 26v. This citation is undated but we could presume it dates to the late 1570s.

78 Ibid., fol. 399v and 399r. See also A.B. Chadour (1980): op. cit. (note 17), p. 204.

79 Christie’s auction, 28 January 2014, lot 175 (ex-collection of Victor Cavendish, 9th Duke of Devonshire).

80 “Una testa d’una Madonna di mano di Scipione gaetano con Cornice Indorate alta palmi uno, et ¾.” Alexandra Dern (2003): Scipione Pulzone (ca. 1546-1598). Weimar, p. 126, no. 31, fig. 37.

81 Medici Archivio (1571-88): op. cit. (note 33), fols. 4v, 4r, 407r. See also A.B. Chadour (1980): op. cit. (note 17), pp. 200 and 205.

82 Ibid., fols. 373v, 373r.

83 Ibid., fols. 2v, 2r.

84 J. Montagu (1963): op. cit. (note 64).

85 State Archives of Rome, Carmerale I, Giustificazione di Tesoreria, vol. 24, fasc. 9. 24 July 1596. See also E. Lamouche (2022): op. cit. (note 38), p. 30.

86 Ibid., pp. 134-35.

87 Ibid., p. 183, see his footnote 160.

88 Deputazione… (1886): op. cit. (note 60), p. 204.

89 A. Bertolotti (1881): op. cit. (note 15). See also E. Lamouche (2022): op. cit. (note 38) pp. 45, 75. Before working for Antonio Gentili, Baldo Vazanno appears to have previously been employed in Bastiano Torrigiani’s workshop as early as 1582.

90 Ibid. In 1605 Baldo Vazanno is tasked with casting a silver Descent from the Cross he had taken a mould from when the original wax model was in Antonio’s studio between 1586-89. See no. 40 in the present catalog.

91 The Medici Archive Project: bia.medici.org (accessed July 2022). Doc ID 15263. Ferdinando’s secretary in Rome, Orazio di Luigi Rucellai, was tasked with this endeavor, appointing Antonio and another unidentified goldsmith to the matter. It is presumed the latter could have been Antonio’s assistant, Baldo Vazzano.

92 Stefano De Mieri (2022): Don Severo Turboli e il cantiere della Certosa di Napoli: precisazioni su Giovanni Antonio Dosio, Lorenzo Duca, Ruggiero Bascapè, Antonio Gentili da Faenza e Pietro Bernini in Il capitale culturale, n. 26, 2022, pp. 13-56. The payments received by Antonio for the continual production of the silver cross for the San Martino Monastery appear to have been variably dispersed between banks and churches in Rome and merchant-banks in Naples.

93 Ibid.

94 Cristoforo Vischer worked alongside his brother, Giorgio Vischer, also a silversmith. Giorgio had fled Rome to Nuremberg, Germany while under persecution from the Roman Inquisition, which was still unsettled by the advent of the Reformation and whose roots were in Nuremberg. Cristoforo’s ailing health prevented him from escaping and upon his death in 1626, his children and estate were held ‘ransom’ in Rome. During correspondence concerning the complicated fate of his estate, Giorgio is cited as having lived in Naples for nine years. It is to be presumed Cristoforo likewise lived and worked with his brother in Naples prior to his earliest debut in Rome before 1597, adjudged by his involvement in the Skills of a Prince relief (no. 4). By 1610 onward Cristoforo is cited as living along via del Pellegrino where Antonio’s workshop was likewise located, by then, presumably under Pietro Gentili’s auspices. If Cristoforo arrived in Rome by 1597, it could be presumed he was active as a silversmith in Naples from 1595, placing him in vicinity of Antonio’s efforts on the silver crucifix for the Monastery of San Martino in Naples from 1593. For the controversies and complexities surrounding Cristoforo Vischer’s estate, see Irene Fosi (2020): Cristoforo Gaspare Fischer: a Goldsmith, his Inheritance and the Inquisition in Inquisition, Conversion, and Foreigners in Baroque Rome. Brill publishing, pp. 71-84.

95 E. Lammouche (2022): op. cit. (note 38), p. 90. See also C. Grigoni (1988): op. cit. (note 1), pp. 97-98, 113.

96 A. Bertolotti (1881): op. cit. (note 15).

97 G. Baglione (1642): op. cit. (note 25), p. 109.

98 Gordon Campbell (ed.) (2006): The Grove Encylopedia of Decorative Arts, Vol. 1. Oxford University Press, p. 417.

Antonio Gentili da Faenza

Autograph Works (nos. 1-4)

No. 1

Farnese Altar Service

Gilt silver inset with lapis lazuli and engraved crystal compositions

Antonio Gentili da Faenza and workshop; Rome, Italy (silverwork)

Giovanni Bernardi (rock crystals, ca. 1546-53)

Muzio Zagaroli (rock crystals, aft. 1553)

1578-81; commissioned by Cardinal Alessandro Farnese

Vatican Treasury

The origins of the Farnese Altar Service are traced to correspondence between the goldsmith, Manno di Bastiano Sbarri, and his patron, Cardinal Alessandro Farnese in 1561.1 Sbarri came to Rome from Florence where he had previously served as a pupil of Benvenuto Cellini.2 The Cardinal had commissioned the production of the elaborate Farnese Casket (fig. 14) from Sbarri as early as 1543,3 having completed it around 1560 following delays due to the Cardinal’s financial pressures.4 5

Fig. 14: Farnese Casket by Manno Sbarri (goldsmith)and Giovanni Bernardi (crystal engraver), 1543-61 (Museo di Capodimonte, Naples)

After Sbarri’s completion of the Farnese Casket, the Cardinal subsequently tasked Sbarri with new commissions for a golden altar cross, two candlesticks, a pax and figures of St. Peter and St. Paul, cited in Sbarri’s petition, on 28 June 1561, to begin work on the project6 and also reiterated in Alessandro’s will of 1574, which indicated the project was incomplete or not begun by that year.7 Sbarri’s subsequent death in 1576 left the project unfinished or altogether unbegun.

However, during the thirteen-year period in which Sbarri presided over the project, designs for the Farnese Altar Service were likely worked out. The initial designs were furnished by Francesco de’ Rossi (called Francesco Salviati) around 1548.8 9 Salviati was presumably also responsible for providing the designs for the Farnese Casket executed by Sbarri.10 Notably, the Farnese Casket has, on occassion, erroneously been thought to involve Antonio Gentili due to the similarity of materials used for both the Farnese Casket and Farnese Altar Service and both having a mutual impetus in Salviati’s imagination.

Delays in Sbarri’s realization of the Farnese Altar Service may have been due to the particular tastes and careful preferences of the Cardinal,11 notwithstanding that the production of the Cardinal’s casket had itself taken eighteen years to complete. Evidence for this lengthy process may survive in a series of goldsmith’s drawings representing what appear to be an early series of iterations on the design of the Farnese candlesticks, two of which are preserved in the Victoria and Albert Museum, and two identified in the art market.12 Each iteration is respectively dated: 1561 (fig. 15), 1562, 1564 and 1571. The earliest iteration interestingly correlates with the year of Sbarri’s petition in 1561 to begin the project.

Fig. 15: Pen and wash rendering of a Farnese candlestick featuring the date, 1561, b. 1670 (private collection)

The Farnese Altar Service shares in common with the Farnese Casket the incorporation of lapis lazuli as well as a suite of engraved rock crystals executed by Giovanni Bernardi de Castelbolognese.13 In discussing the Farnese Casket, Giorgio Vasari noted it’s crystals were based on “the cardinal’s most beautiful fancy,”14 worked after designs furnished by Perino del Vaga and “other masters.”15 At least one of Perino’s sketches for Bernardi’s crystals incorporated on the Farnese Altar Service survive: the Raising of Lazarus at the Louvre (inv. RF 539).16 Perino’s sketches for these religiously themed crystals appear derived from the decorations he made around 1538-39 for the Cappella Massimi in Trinità dei Monti, destroyed during the 19th century, of which only a fragment survives in the Victoria & Albert Museum (inv. 262-1876).17

While the Farnese Casket’s crystals reflected mythological subjects pertinent to the Cardinal’s humanist and political ambitions, the Farnese Altar Service depended instead upon religious subjects pertinent to the form and function of its sacred use. However, certain details still infer the calculated ingegno of Alessandro in its inception. This is most evident in features incorporated on the Farnese Altar Service like the armorial along the base of the altar cross depicting a ribbon bearing the Greek inscription: ΔΙΚΗΣΚΡΙΝΟΝ, meaning “Lily of Justice,” a Farnese family motto attributed to Alessandro, as described in a letter by Alessandro’s secretary, Annibale Caro, to the Duchess of Urbino.18

The continued familial theme is present also in the feature of lilies on the terminating ends of the altar cross and is likewise implied by the subtle series of lilies in the form of two volutes surmounted by an orb which serve as a type of crocket décor bordering the outer margins of the altar cross. The Farnese impresa of the unicorn (figs. 2, 9) also forms part of its imagery, symbolizing virtue overcoming vice.

The elevation of the Farnese-themed iconography present on the Farnese Altar Service is perhaps indebted to the changes made during the realization of the Farnese Casket in which some elements that could have been misread as supporting the Holy Roman Empire of Charles V, with whom tensions were mounting, resulted instead in an iconography ensuring a clear association with, and affirmation of, Farnese familial unity.19 Similar motifs were expressed during renovations of the Farnese chapel within the Palazzo della Cancelleria, overseen by Salviati during the late 1540s, and their familial emblems likewise appear at Farnese sponsored projects like Paul III’s addition to the Vatican loggie and renovations made to the library at Castel Sant’Angelo.

The particular feature of an arrow accompanying a banderole with the Greek inscription: BAΛΛ OYTΩΣ, also on the base of the altar cross, refers to Homer’s words, “strike thus,” meaning to hit the target spot-on and symbolizes success in forwarding a just cause, in this case, that of the Roman reformation of the church under Farnese auspices.20

The edification of the Farnese name on the altar service is thus a thematic and motivated calculation on the part of Alessandro and features also on the Farnese Ostensory attributed to Antonio (no. 6) which features a figural effigy and armorial in tribute to the Cardinal’s grandfather: Pope Paul III.

Apart from Vasari’s mention of Bernardi’s contribution to the Farnese Altar Service, a letter from 4 April 1546, between Alessandro and Bernardi, discusses his completion of four of the Farnese Altar Service crystals.21 Bernardi’s death in 1553 seems to have left three of the required crystals for the altar service unrealized. The scenes depicting Christ and the Captain of Capernaum, the Crowning of Christ with Thorns and an autographed crystal depicting the Healing of the daughter of Jairus22 were subsequently executed by Bernardi’s pupil and assistant, Muzio Zagaroli.23

Sbarri’s death in 1576 necessitated the Cardinal’s reassignment of the project to Antonio.24 At this time, aged fifty-nine, Antonio was already an established master, having formerly served as Chamberlain of the Confraternity of Goldsmiths in Rome and active during this period also as a member of its Consul. The Cardinal would pay a substantial 18,000 scudi for Antonio’s completion of the project.25 After four years of work Antonio delivered the project in 1581 and on 2 June 1582, the Cardinal donated the altar service to the canon of St. Peter’s Basilica, Aurelio Coperchio. The Farnese Altar Service remains in the basilica’s treasury to-this-day.

While it is unclear how much of Sbarri’s efforts were devoted to the Farnese Altar Service prior to Antonio’s inheritance of the project, some scholars have put forth various ideas about Sbarri’s potential involvement in its particular features. For example, Wolfgang Lotz suggested the aediculae and its figures of sibyls and prophets in their niches along with the figure of Christ for the crucifix and the cross, sans its terminals, were the possible work of Sbarri,26 although the crucifix is now recognized as deriving from a model by Guglielmo della Porta, to be discussed. Some of Lotz’s observations were calculated from a sketch of the base of the altar cross initially attributed to Antonio at the Cooper Union Museum in New York but more recently considered a work by Carlo Spagna who later made a series of studies of Antonio’s cross for the production of four additional candlesticks to accompany the altar service, to be discussed.27 The invention of the winged Victories circumnavigating the upper shaft and the figures of the Atlases along the base of the cross have also been suggested as Sbarri’s work.28

However, the lack of progress on the project, indicated by the Cardinal’s will of 1574 suggests it may not have progressed much, if it all, and it is evident by the Cardinal’s will that Bernardi’s crystals certainly had not yet been set into the cross and candlesticks by this time and these were certainly integrated by Antonio.29

The four dated drawings for one of the candlesticks, previously discussed, may testify to the lack of progress made during Sbarri’s tenancy of the commission.30 The group of presumed preliminary drawings for the candlestick informs that only minor edits were made to its design over a nine-year period, suggesting the Cardinal’s final approval for the candlestick’s design was a tenaciously protracted process or that the initial commission was beset by certain unknown delays, some perhaps due to changing tastes on account of church reforms. The slight differences between these designs suggest Sbarri may not have begun any tangible work on the candlestick until at least after the latest dated drawing of 1571, allowing only a period of five years to complete any of its parts. However, the large sum Antonio is paid to execute the project seems to insist he is handling the effort entirely from its outset.

On stylistic grounds, Beatriz Chadour suggested the entire altar service to be the work of Antonio and his workshop, drawing from the contemporary Mannerist influences of sculptors like Michelangelo, Guglielmo della Porta and Andrea Sansovino while embellishing his own heterogenous panache to the mix.31 Certain sculpted and decorative features of the Farnese Altar Service appear to be the product of assistants to which she assigns provisional names. Antonio’s son, Pietro, training under his father during his late teens, may also have had an involvement in some of the production. During this period, we are aware of at least one of the collaborators active in Antonio’s workshop: Carlo Boni da Faenza, who we can assume played some role in the execution of the altar service. Chadour’s suggestions that Antonio was responsible for the project carry additional weight when considering also the style, quality and exceptional figures adorning the Farnese Ostensory attributed to Antonio (no. 6).

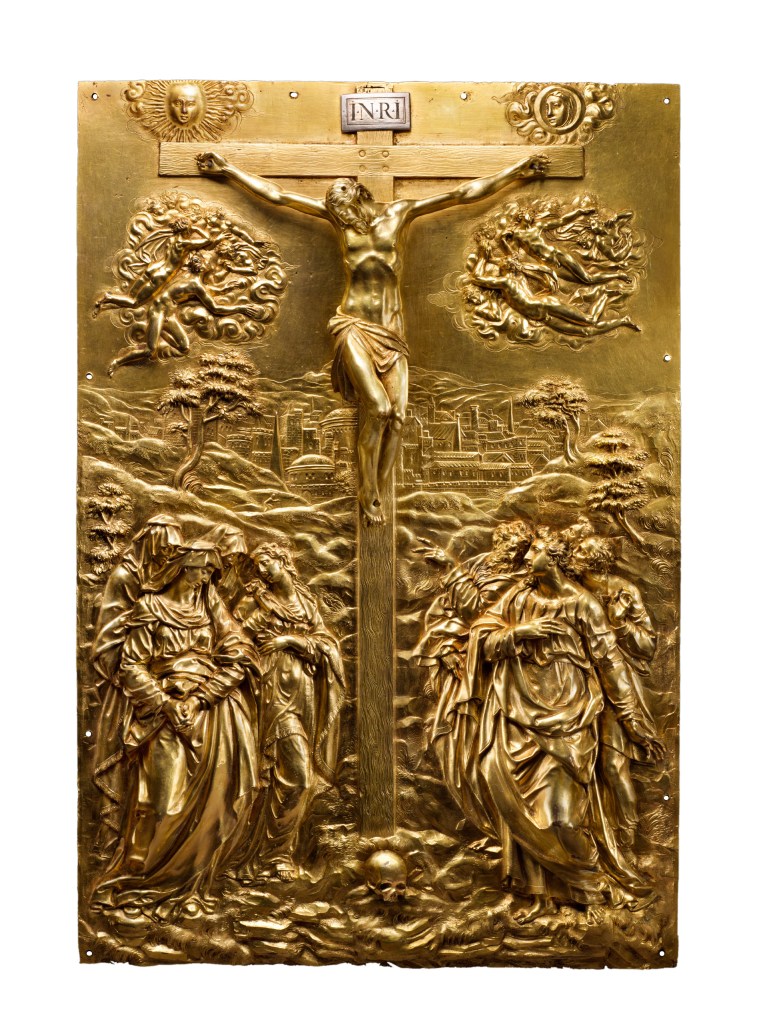

Although Angelo Rocca’s publication, De particular ex pretioso et vivifico ligno santissimae crucis, published in Rome in 1609, cites Sbarri as the author of the cross and candlesticks,32 Antonio’s signature along the concealed support shaft for the altar cross: ANTONIO GENTILI FAENTINO F., is further evidence for Antonio’s exclusive execution of the work (fig. 16).33 Additionally, the engraved print of the altar cross (fig. 9), believed executed by Antonio, ca. 1589-1609, likewise claims his creation of the work, sans the crucifix which is omitted from the engraving possibly because Antonio desired not to claim authorship for its invention as the model was a known creation of Guglielmo della Porta’s, reproduced further by other metalsmiths connected with his workshop (nos. 7-9). C.D. Dickerson further emphasizes Antonio’s lack of claim for the original disegno of the altar cross, as implied by the manner of his signature which omits the use of the term: OPUS.34

Fig. 16: Signed mounting shaft for the Farnese Altar Cross by Antonio Gentili da Faenza, 1578-81, (Treasury of St. Peter’s, Rome)

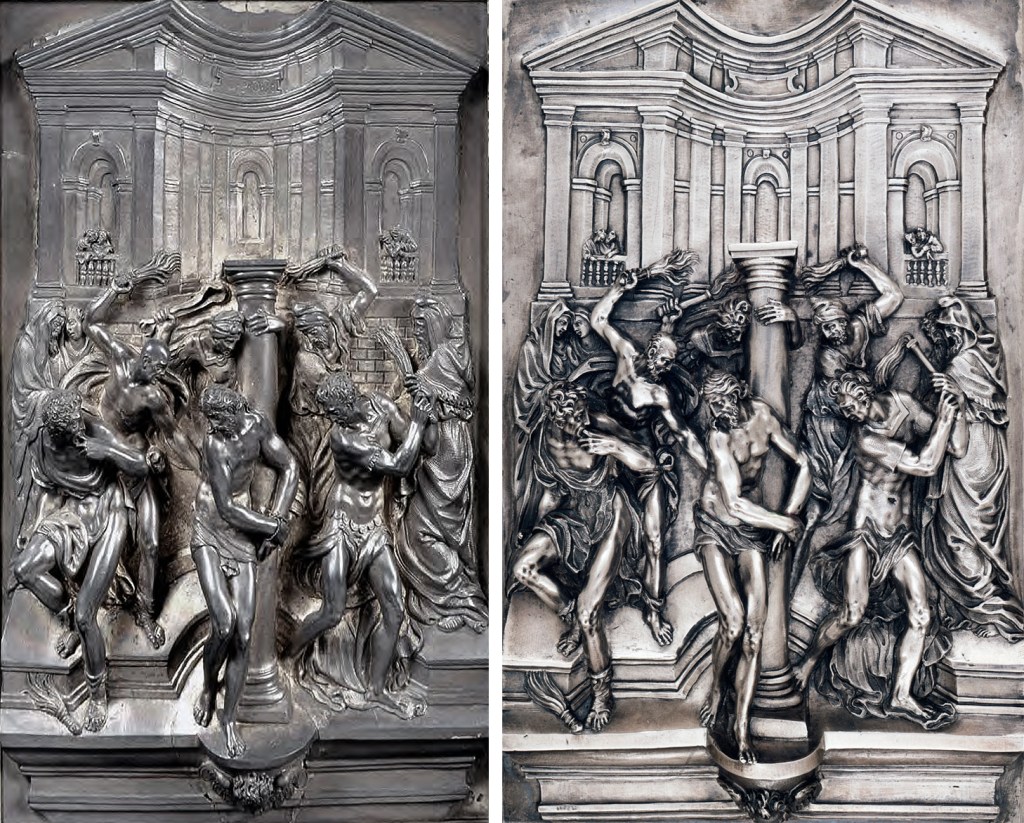

The use of Guglielmo’s crucifix-model for the Farnese Altar Cross may have been the choice preference of the Cardinal himself notwithstanding both Guglielmo and Antonio were actively working for the Cardinal at-this-time. The Cardinal was made aware of Guglielmo’s crucifix when he received an example sent to him as a gift from Guglielmo, resulting in a letter of praise and gratitude from the Cardinal, to Guglielmo, in 1571.35 The reprisal of Guglielmo’s crucifix-model, cast and incorporated by Antonio for the altar cross (fig. 17, right), is made evident in court documents in which a trial initiated by Guglielmo’s son, Teodoro della Porta—concerning the illegal use of his father’s models by certain metalsmiths in Rome—provides a testimony given by Giovanni Battista Montano who infers Antonio’s employ of Guglielmo’s crucifix-model for inclusion on the Farnese Altar Cross.36 Other metalsmiths like Guglielmo’s collaborator, Bastiano Torrigiani, likewise reproduced and slightly reinterpreted this same crucifix-model in gilt bronze for an altar cross commissioned by Pope Gregory XIII in 1583, also preserved today in the treasury of St. Peter’s Basilica.37 Guglielmo’s crucifix-model was likely further reproduced by Antonio and Torrigiani, several additional casts of which have been ascribed to these metalsmiths.38 Guglielmo’s workshop certainly produced a great number of them as adjudged by the quantity of crucifixes remaining in his workshop after his death.39

Antonio observably embellishes Guglielmo’s original crucifix-model with his own interpretive form and style by removing the sign of blessing made by Christ’s proper right hand, raising his arms approximately 1.2 cm, and centering Christ’s head over his chest. More importantly, Antonio tempers Guglielmo’s model, reducing the stress of Christ’s musculature while softening the features of his face. He also exchanges Guglielmo’s signature inverted triangular umbilicus with a circular one and transforms the tousled sinewy strands of Christ’s hair into a subdued form that is less bodied while the beard is given more volume and is shortened (fig. 17).

Fig. 17: A gilt copper crucifix attributed to Guglielmo della Porta, ca. 1570 (left; Capponi family, Rome); detail of the Farnese Altar Cross, Antonio Gentili, 1578-81, after a model by Guglielmo della Porta (Treasury of St. Peter’s, Rome)

This reserved treatment and tempering of Guglielmo’s model allows further comparisons between Guglielmo’s own workshop casts of his inventions and those casts produced alternatively in Antonio’s workshop. This same treatment is observed in other casts Antonio executes after Guglielmo’s models like his relief of Mount Calvary (nos. 7-9), the Risen Christ (no. 10), and Flagellation of Christ (no. 11). Satisfying comparisons may also be drawn with a gilt silver corpus Guglielmo made as a gift for Maximilian II of Austria in 1569, preserved in the Kunsthistorisches’s Geistliche Schatzkammer in Vienna.40 The softened features and matte-like finishing of this crucifix are indicative of Antonio’s casting quality and may be a work cast by Antonio on behalf of Guglielmo, who, during this period, was actively collaborating with him on the realization of twelve reliquary busts for Pope Pius V in 1570 (no. 14).41

The format for the Farnese Altar Service project, by the time of Antonio’s adoption of it in 1578, appears to lack the pax and figures of Sts. Paul and Peter initially forming part of the original commission. Chadour notes that the group consisting of a central altar cross inclusive of a figure of Christ and its flanking candlesticks are in-keeping with the reforms instituted by Pope Pius V, beginning in 1566, and reaching a standardized formula in his 1570 Missale Romanum, possibly influencing Alessandro’s choice reduction of the overall project, although the Farnese Ostensory could be a later incarnation of the original commission, if not the product of Alessandro’s patronage or possibly that of Cardinal Odoardo Farnese, who had commissioned the binding for the Farnese Hours from Antonio (no. 4).42 The figures of Sts. Peter and Paul on the ostensory almost certainly have their impetus in the original vision for the Farnese Altar Service suite.

Concerning the materials for this ambitious project, the records of Giacomo Grimaldi, preserved in the Vatican, suggest the silver provided to be used for the Farnese Altar Service had been sourced from the remnants of Charlemagne’s cross, melted down in 1550.43 The cross was a donation given by Charlemagne on the occasion of Pope Leo III’s coronation in 800. However, the matter is much more complicated and the silver melted down in 1550 appears to instead derive from the remnant of a gilt silver crucifix donated by Pope Innocent II during the 12th century, the weight of which was a staggering 100 pounds.44

As previously noted, in 1670, the Archpriest of the St. Peter’s Basilica, Cardinal Francesco Barberini, commissioned the stem of the Farnese Altar Cross to be lengthened, recruiting the Roman goldsmith, Carlo Spagna, to execute the embellishments in addition to creating four additional candlesticks to enlarge the suite, completed between 1670-72.45 Spagna’s modification to the altar cross incorporates a voluted knop featuring the Barberini familial bee-motif just below the upper stem portraying the Victories.

It is to be wondered if Barberini, at this time, may have also removed what could have been an enameled Farnese armorial presumably once featured on the altar cross. It is unusual that the cross lacks this accoutrement which appears on both the Farnese Casket by Manno Sbarri and the Farnese Ostensory attributed to Antonio.46

No. 2

Gold setting for a Bust of Caesar Augustus

Colored glass paste bust on a modeled gold body mounted to an agate base

Antonio Gentili da Faenza and workshop; Rome, Italy (goldsmithing)

1580; commissioned by the Grand Duke of Tuscany, Ferdinando de Medici

Museo degli Argenti, Palazzo Pitti, Florence

The golden setting for a glass paste bust of Emperor Caesar Augustus is the only securely identified work by Antonio during his period of activity for the Medici. An entry in the Medici inventories, kept in the State Archives of Florence, confirms Antonio’s creation of the setting for the bust.47 However, a silver pax featuring a relief of the Risen Christ Surrounded by Apostles, still residing in the Treasury of the Grand Dukes at the Pitti Palace in Florence (no. 10), is another possible vestige of Antonio’s activity under Medici patronage.

Antonio’s setting displays a turquoise-colored glass paste bust of Emperor Augustus, mistakenly identified in earlier literature as a bust of Emperor Tiberius.48 49 Antonio’s setting is exquisite in detail and refinement, being a testament to his skill during this central point of his career. The bust pivots gracefully upon Antonio’s all‘antica invention of a Roman cuirass whose subtle scarf bursts eloquently from the neckline while the armored portion introduces serpentine-inspired volutes and acanthi tendrils which frame the grotesque effigy of Medusa. Antonio’s frequent use of volutes and his talent in rendering masks in low-relief are brought to bear in this stunning example of delicate and refined workmanship.

Antonio appears to have referenced a contemporary knowledge of antique military attire, born from the availability of antiquities in Renaissance Rome and probably also indebted to circulated sketches like those preserved in the Uffizi (invs. 548O, 549O). His familiarity with the Trajan column may also have suited well for this project.

The agate base of the bust may have been furnished by the stone carvers later active in the Opificio delle Pietre Dure, established in 1588 under the auspices of Ferdinando de’ Medici, by then the new Duke of Tuscany, and responsible for precious works executed in colored stone. Two other works for the Medici that were made by Antonio from this period likewise incorporate agate elements, like the orbs serving as the feet for a silver and gold tabernacle he executed in June of 158250 (no. 25) and a golden band or setting he made for a small agate cup, perhaps antique, made probably ca. 1580-82 (no. 23).51

No. 3

Book binding for the Farnese Hours

Engraved and openwork parcel gilt silver

Antonio Gentili da Faenza and workshop; Rome, Italy (silverwork)

1589-94; commissioned by Cardinal Odoardo Farnese

Pierpont Morgan Library, NY (inv. Ms M.69a)