by Michael Riddick

Preview / download PDF in High Resolution

Preview Italian version at Antiqua Nuova Serie

PART 4 of a SERIES OF FIVE PLAQUETTE STUDIES CONCERNING MODERNO AND HIS SCHOOL

Galeazzo Mondella, called Moderno, was the most prolific producer of small bronze reliefs of the Renaissance. While some of his productions were evidently conceived as independent works-of-art others were likely intended to be grouped in a series. Further examples ostensibly sought to preserve creations conceived by him originally in more precious materials.

Throughout the course of scholarship various bronze plaquettes attributed to Moderno have instead been reallocated to followers or presumed anonymous workshop assistants. These artists are today identified by pseudonyms like the Master of the Herculean Labors, the Coriolanus Master, Master of the Orpheus and Arion Roundels, Master of the Corn-Ear Clouds, the Lucretia Master, et al.

While many of these pseudonyms have been applied only in the last few decades, the proposed identity of these artists or their possible reassessment back to Moderno has been little explored due to an absence of information or further critique. However, certain observations may yield reasonable suggestions concerning their context or authorship, particularly as regards the work of Matteo del Nassaro, a gem-engraver whom Giorgio Vasari noted had been a pupil of Moderno as well as a pupil of Moderno’s Veronese contemporary Niccoló Avanzi.

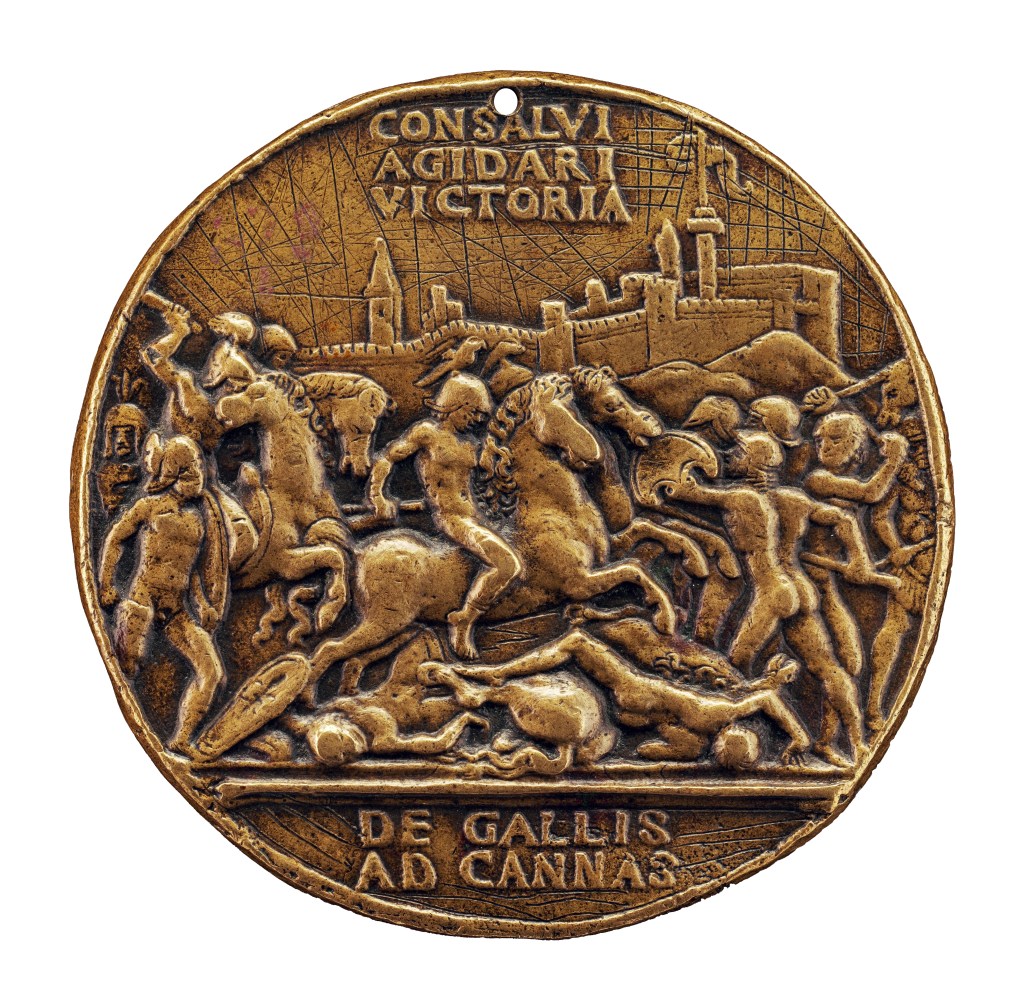

Fig. 01 – Obverse of a bronze medal depicting the Battle of Cannae, by Hermann Vischer der Jüngere (?), after Galeazzo Mondella, called Moderno, made ca. 1506-07 (?), Venice (?) (National Gallery of Art, DC, inv. 1957.14.273.a)

The authorship of a medal celebrating the Battle of Cannae has occasionally entertained a dual attribution in scholarship (cover, fig. 01). The Battle Scene depicted on the obverse of the medal has traditionally been attributed to Moderno or his ambit,1 and for the last century, to another anonymous artist in Moderno’s circle, dubbed the Coriolanus Master,2 whose same battle scene is alternatively described as Coriolanus Fighting Under the Walls of Rome on account of its feature among a series of additional small plaquettes depicting scenes from the story of Coriolanus—known by independent casts—and preserved collectively on an inkstand at the Victoria & Albert Museum (fig. 02).

Fig. 02 – Side of a gilt and silvered bronze ink casket with a Battle Scene (right), attributed to the Coriolanus Master, ca. 1500, Italy (Victoria & Albert Museum, inv. M.167-1921)

In spite of this complication, the Battle Scene’s execution is almost certainly due to Moderno’s authorship as adequately demonstrated by Douglas Lewis.3 Lewis notes its derivation from earlier compositions attributed to Moderno like the reverse of his medal for Agostino Mazzanti and his autograph Senatorial Triumph relief which appears variably in plaquette form and as the reverse for medals. Furthermore, the example of the relief produced by the Coriolanus Master truncates the original circular composition of the scene into a debased rectangular format. Its composition derives from antique sources4 and is connected with a Lion Hunt roundel by Moderno as well as a battle scene plaquette representing dubious fortune and featuring the legend DVBIA FORTVNA. The elements of these compositions collectively reach their zenith in a Battle Scene cameo, probably by Moderno, and formerly in the Duke of Orleans collection.5

Moderno’s Battle Scene and DVBIA FORTVNA compositions appear to have been spread as models that found their way into various workshop environments. As noted by Lewis, Andrea Briosco, called Riccio, appears to have borrowed the latter for the invention of his Combat at a City Gate bronze relief and Severo da Ravenna reproduces an example of it beneath the foot of a Chimera sculpture attributed to him.6 It would seem likely that Moderno prepared this composition, and its corollaries, as an independent artwork and its diffusion among peers or other workshops led to its subsequent appropriation by the Coriolanus Master (if not identifiable as Moderno himself)7 and the producer of the Cannae medal. The fidelity of the relief on the Cannae medal is already suffering in the quality and suggests it was probably sourced from an aftercast.8

Moderno’s designs were circulated posthumously, as observed by the business partnership made by his son and nephews after his death,9 and likewise observed by the feature of quality casts of his models found in Paduan bronzes produced later in the workshop of Desiderio da Firenze.10 Evidence for the contemporaneous use of his models within other workshops is noted also by a 1522 document citing a Venetian goldsmith that was in possession of a ‘Saint George on horseback with a dragon, in the form of a wax model by the hand of Moderno,’ intended to be used in the production of a diamond brooch.11 This model by Moderno has been linked with a relief typically associated with an assistant operating in Riccio’s workshop and making use of the warrior featured on the aforenoted DVBIA FORTVNA composition which is sometimes attributed to Moderno, and other times, to his workshop.12

Moderno’s small Battle Scene composition used on the Cannae medal must date to the first years of the 16th century, following after the earlier battle scene medal reverses made in Mantua during the 1490s and dating around 1503-05 or 1508, while he is believed to have been active in Rome.13

As previously noted, the original Battle Scene was realized in circular form and probably lacked a legend. The raised legend on the Cannae medal is disparate from other legends featured on Moderno’s plaquettes and medals and was evidently added by a different hand. Notably, the legend ingeniously commemorates the victory of Hannibal over the Romans at Cannae in 216 BC and is reimagined in the conquests of the French during the Italian campaigns by the “Great Captain” Gonzalo Fernandéz de Córdoba y Aguilar whom, at the Battle of Cerignola near Cannae, defeated the French in April of 1503.

Fig. 03 – Obverse and reverse of the gilt bronze hilt for the sword of Gonzalo de Córdoba, ca. 1504-15 (Royal Armoury of Madrid, inv. G 29)

Based upon this date, the Cannae medal has most frequently been considered made shortly after the battle. The medal forms the hilt of a sword once belonging to Córdoba14 (fig. 03) that was originally believed to have been given to him by Pope Alexander VI sometime between April and August of that year: post-ceding the date of the battle it commemorates and preceding the death of the pontificate. However, more recent scholarship has dated the sword to 1504-15 and is now understood to have been given to Córdoba by Pope Julius II.15 Julius II, ‘the warrior pope,’ also gifted other commissioned swords during his tenure, like those he gave to the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I and to King James IV. Recent analysis of the sword has confirmed it was produced in Italy16 and based upon its style, it is probably the work of a swordsmith in the Veneto apparently using the monogram “P.”17

Determining a date for the Cannae medal may be further narrowed through our understanding of its feature on Jean Grolier’s binding of Philostratus. In particular, the dating for the edition of Grolier’s copy of Philostratus is debated, believed printed anywhere between 1501-04 and Paul Needham has theorized the most probable dating for the binding rests somewhere around 1509-10.18 These observations altogether narrow a probable dating for the Cannae medal between 1504-09 with Moderno’s original invention of the model presumably executed sometime before this, probably in 1503-05 on account of its clear Roman influence.

The feature of the Battle Scene composition on the Cannae medal has frequently led scholarship to inadvertently ascribe the entire medal or its obverse to Moderno or the Coriolanus Master, however, Lewis has aptly noted that while the original Battle Scene is certain to be Moderno’s invention, the medal only appropriates the design and the overall medal is altogether ‘so eccentric as to stand in some degree outside the Italian medallic tradition,’ commenting also that the medal is, ‘in a way,’ Germanic.19

The present author here interjects a further, albeit adventurous, exploration of Lewis’ observation. The medallic tradition was chiefly reserved to Italy throughout the 15th century and while the Cannae medal does suggest a German essence, the medallic tradition in Germany is generally not understood to begin until 1507 by way of the Vischer family of bronze founders active in Nuremberg.20

A minority of medals representing the genesis of this art in Germany are generally ascribed to Peter Vischer the Younger, the middle-son of Peter Vischer the Elder who presided over a quantity of important commissions in bronze during the late 15th and early 16th centuries. The earliest German medals represent portrait busts of Peter Vischer the Elder’s two eldest sons: a medal of Hermann Vischer the Younger from 1507 (fig. 04) and a medal of Peter Vischer the Younger from 1509.21

The present author has contended that these medals commemorate the return of these sons from their wanderjahre, a German rite-of-passage traditionally expected of guild members following their apprenticeships and typically occurring around the age of 19 or 20.22 The medal depicting Hermann Vischer the Younger features a reverse probably depicting the Pillars of Hercules, which the present author has suggested is an allegory referring to Hermann’s return from Italy with newfangled knowledge. Following the untimely death of his wife in 1513, Hermann is documented as having made a trip to Rome returning with a quantity of sketches for use in their workshop, to which the present author has formerly suggested was a possible reprise of his proposed wanderjahre of 1507.23

While the portrait medal of Hermann was probably realized in Germany in 1507, it is to be assumed he would have initially experimented with the art of medal making during his supposed wanderjahre, ca. 1506-07. Hermann’s knowledge of bronze casting would have logically connected him with others working in this same medium and Nuremberg’s ties to the arms industry may have presented his candidacy to prepare such an artwork for possible incorporation on a sword hilt, aside from the prestige associated with his father’s workshop as the premier bronze foundry of Germany.

If Hermann’s wanderjahre occurred in Italy ca. 1506-07 we would assume an initial passage occurred through Venice where there was a significant German population and a well-established German-Venetian mercantile industry.24 We may recall Albrecht Dürer’s initial travels to Italy, arriving and staying in Venice both in 1494 and again in 1505.25 Dürer certainly knew the Vischer’s, providing the designs for the bronze tomb for Count Hermann VIII of Henneberg and his wife, Elizabeth, Countess of Brandenburg, in 1512-13, whose casting was the product of the Vischer workshop, and a project also occasionally ascribed to Hermann Vischer the Younger. Dürer would later collaborate with the Vischer’s on other projects large and small and Hermann’s friend, Wolf Traut, worked in Dürer’s studio.26 If Hermann the Younger made his wanderjahre during this period he would have done so while Dürer was likewise in Venice.

Another hypothetical impetus for traveling to Venice for his wanderjahre might be due to the influence of the Venetian painter Jacopo de’ Barbari who moved from Venice to Nuremberg in 1500 and had a significant impact on the artists in that city. Jacopo’s provision of the designs for Peter Vischer the Elder’s execution of the graveplate for the tomb of Duchess Sophie of Mecklenburg in 1504,27 would have entailed the young Hermann’s impressions of this Venetian master whom likewise had made a great impression upon Dürer.

Notably, Moderno was especially active in Venice during this period and is documented there for at least two weeks28 whilst also serving his second incumbency as head of the goldsmith’s guild in Verona. He appears to have been commissioned by various Venetian clients at-this-time, indicated by inscriptions featured on casts of his small Madonna and Child with Two Standing Angels reliefs datable to this period as well as his masterpiece group of the Flagellation of Christ and Sacra Conversazione for Cardinal Domenico Grimani and the elaborate sword hilt probably executed for the Venetian commander Giorgio Cornaro.29 Given their shared industry in bronze founding, it would seem possible Hermann the Younger, if in Italy or the Veneto at-this-time, would have encountered Moderno, perhaps even serving in his workshop or ambit, if not becoming familiar with his creations through other channels.30

Fig. 04 – Obverse and reverse of a brass self-portrait medal of Hermann Vischer der Jüngere, 1507, Nuremberg (left and center, Cabinet des Medailles, Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris); Reverse of a bronze medal depicting the Battle of Cannae, by Hermann Vischer der Jüngere (?), ca. 1506-07 (?), Venice (?) (right; National Gallery of Art, DC, inv. 1957.14.273.b)

The remainder of the Cannae medal—its inscription and reverse—might theoretically be Hermann’s handiwork, as there is a particular consonance between the scale and naïvely realized depiction of Hercules and Janus on the reverse of the Cannae medal and that of Hercules on the reverse of Hermann’s portrait medal (fig. 04). The crudely articulated legend on the Cannae medal recalls the hand of a woodcutter still influenced by Gothic German letter-types, as also observed on Hermann’s medal and most notable perhaps, is the clever classicized idea behind the Cannae medal which is similarly reflected in Hermann’s portrait medal. The Vischer’s interest in the classical world and humanism was integral with the influence of their Nuremberg peers and patrons inclusive of Hartmann Schedel, Sebald Schreyer and Pangraz Schwenter.31 We may note for example, Peter Vischer the Younger’s drawings based upon the latter’s German translation of the Histori Herculis, or the same artist’s clever depiction of Martin Luther as Hercules in his allegorical drawing of the Victory of the Reformation.32

Regrettably, Hermann’s untimely death and the minimal information concerning his activity as a sculptor provides little or no understanding toward his creative ability. Even his 1507 portrait medal is often unfairly ascribed to the invention of his younger brother rather than to him even though there is little stylistic coherence between them.33 Nonetheless, his theoretic presence in Italy in 1506-07 and his presumed experimentation in medal making, would present an adequate timeline that resonates with the invention of the Cannae medal and its subsequent feature on the sword for Córdoba.

The Cannae medal appears to have made its way throughout Europe, employed as the reverse for subsequent medals of Francis I (after 1515), a German medal of Charles V of Spain (after 1519) and in a much-debased form on a posthumous medal of Louis II of Hungary, dated 1532 and attributed to Michael Hohenauer.34 In addition to the early German medal of Charles V of Spain it also appears as part of a border treatment—among other plaquette-based compositions—in the 1521 German prayer book of Matthäus Schwarz illuminated by Narziss Renner in Augsburg.35

Fig. 05 – Obverse and reverse of a bronze medal of Elvira de Córdoba, 1524 (?), after Moderno (obverse) (National Gallery of Art, DC, inv. 1957.14.1116.a-b)

Another scarce medal related to the Córdoba family, and likewise brought to our attention by Lewis, features an additional appropriation of a model by Moderno.36 The medal is possibly a memorial to Elvira de Córdoba, the daughter of the ‘Great Captain,’ who died prematurely in 1524. The medal features a fictional depiction of her by way of a crudely edited relief of Moderno’s high-relief model of Faustina37 while the reverse features a naively realized scene of Death and Peace Closing the Door of the Temple of Janus (fig. 05). It is perhaps not unreasonable to also suggest a loosely potential origin for this medal within the Vischer workshop. In particular, its format recalls a closely dated, ca. 1525, medal of Sebald Rechs which is assigned to the Vischer workshop38 and features a similar visual format albeit the legend on Elvira’s medal is much more Italianate than German (fig. 06).

Fig. 06 – Obverse and reverse of a lead medal of Sebald Rech, ca. 1525, attributed to the workshop of Peter Vischer der Jüngere, Nuremberg (Germanisches Nationalmuseum, inv. MED 10597)

Endnotes:

1 Èmile Molinier first suggested the Master signing IO.F.F. was responsible for these compositions. Èmile Molinier (1886): Les Bronzes de la Renaissance. Les plaquettes. Paris, nos. 140 and 634.; Wilhelm Bode was first to attribute them to Moderno. Wilhelm von Bode (1904): Beschreibung der Bildwerke der Christlichen Epochen: Die Italienischen Bronzen. Berlin, Germany: Konigliche Museen zu Berlin, no. 786; Erik Maclagan diverged slightly with an association to the school of Moderno. Erik Maclagan (1924): Catalogue of Italian Plaquettes. Victoria and Albert Museum, London, p. 41; and Ernst Bange suggested a Paduan artist working with Moderno. Ernst Bange (1922): Die Italienischen Bronzen der Renaissance und des Barock. Zweiter Teil: Reliefs und Plaketten. Vereinigung Wissenschaftlicher Verleger Walter de Gruyter & Co., Berlin and Leipzig, Germany, no. 508.

2 Seymour de’ Ricci agreed with Bange’s assessment of a Paduan origin by an artist under the immediate influence of Moderno, dubbing him the “Coriolanus Master.” Seymour de’ Ricci (1931): The Gustave Dreyfus Collection. Reliefs and Plaquettes. Oxford, no. 148, p. 118.

3 Douglas Lewis (1987): The Medallic Oeuvre of “Moderno”: His Development at Mantua in the Circle of “Antico” in The History of Art, vol. 21, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, pp. 77-97 and Douglas Lewis (1989): The Plaquettes of ‘Moderno’ and His Followers in Studies in The History of Art, vol. 22, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, pp. 105-41.

4 The battle scene recalls other battle and hunting scenes derived from classical Roman sarcophagi and the Great Trajanic Frieze on the Arch of Constantine. See D. Lewis (1989): op. cit. (note 3). Although Lewis suggests its design may have been developed from drawings from his friend, Giovanni Maria Falconetto, who spent time in Rome, it is perhaps also possible Moderno utilized these sources while he was in Rome himself during certain periods of the first decade of the 16th century. Michael Riddick (2024a): Reapproaching the Coriolanus Master as Moderno and a collaborator in Rome. Renbronze.com (accessed January 2024).

5 D. Lewis (1989): op. cit. (note 3). Attilio Troncavini has also discussed the relationship between these compositions in Attilio Troncavini (2019): Fonte da o per il Moderno. Antiquanuovaserie.it (accessed May 2023).

6 Bode Museum, inv. 1943

7 M. Riddick (2024a): op. cit. (note 4).

8 The design is even further reduced in quality and perhaps afterworked for the example featured on the sword for Gonsalvo de Córdoba.

9 Michael Riddick (2023): Moderno and Associated Makers. Renbronze.com (accessed January 2024).

10 Satisfactory casts of Moderno’s compositions appear to have been reproduced in Padua from around 1530 and appear on bronze productions executed by Desiderio da Firenze. D. Lewis (1989): op. cit. (note 3). See also Jeremy Warren (2016): The Wallace Collection. Catalog of Italian Sculpture. The Trustees of the Wallace Collection, London and M. Riddick (2017): A selection of plaquettes from the Villa Cagnola: Their Function and Meaning, Renbronze.com (accessed June 2023).

11 Clifford Brown (1997): The Archival Scholarship of Antonino Bertolotti – A Cautionary Tale in Essays in Honor of Carolyn Kolb, Artibus et Historiae. Vienna-Krakow, p. 68 ff.

12 E. Bange (1922): op. cit. (note 1), no. 386, p. 53.

13 Francesco Rossi (2011): La Collezione Mario Scaglia – Placchette, Vols. I-III. Lubrina Editore, Bergamo, pp. 165-66, and 236.

14 The original sword is preserved in the Real Armory of Madrid, Inv. G 29. We may note the use of another ‘Corliolanus’ relief on a sword hilt preserved at the Museo Correr. This sword hilt features the Coriolanus Master’s Coriolanus and the Women of Rome composition. See Emil Jacobsen (1893): Plaketten im Museo Correr zu Venedig in Repertorium fur kunstwissenschaft, xvi, p. 68.

15 Gabriel Pozo Felguera (2017): Localizamos las dos espadas más queridas del Gran Capitán, desaparecidas de su panteón en San Jerónimo hace varios siglos in El Independiente de Granada, 23 July 2017. (www.elindependientedegranada.es/cultura, accessed December 2023). It should be noted that several antique copies of the sword exist and the example kept in Madrid’s Royal Armory appears to be the original, having been cited also in a 17th century inventory. A redacted version of the Cannae medal appears in the form of a sword hilt in the Louvre, donated in 1856, and in the present author’s opinion, could be the product of one of these antique copies of Córdoba’s sword (see Louvre inv. OA 769 and/or OA 7346).

16 Centro de Publicaciones del Mº de Defensa (2015): Catálogo exposición El Gran Capitán. Museo del Ejército, Toledo.

17 There appears to be one particular swordsmith of the Veneto using this monogram during the late 15th century, although the present author is not aware whether the monogram aligns accordingly with that featured on the sword of Gonzalo de Córdoba. The monogram could refer to the swordsmith known as Maestro Pippo. See for example nos. 142, 144, and 146-149 in Lionello Boccia and Eduardo Coelho (1975): Armi Bianchi Italiane. Bramante Editrice.

18 Paul Needham (1979): Twelve Centuries of Bookbinding, exh. cat., Pierpont Morgan Library, pp. 139-43.

19 D. Lewis (1987): op. cit. (note 3).

20 The present author identifies one medal of Peter Vischer the Elder’s first wife, dated 1490, but it is to be questioned whether this medal was made in 1490 or perhaps developed later once the Vischer workshop became more aware of the medallic tradition by way of their documented ties to Italy, possibly in 1508-09 and certainly by 1513. For the documentary references concerning the Vischer family in Italy see Michael Riddick (2020): The Earliest German Medal? Peter Vischer der Altere’s Memorial Medaille to His First Wife Margaretha. Renbronze.com (accessed January 2024).

21 Hermann Maué (1986): The Development of Renaissance Portrait Medals in Germany in Gothic and Renaissance Art in Nuremberg 1300-1550, Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY, pp. 105-07.

22 Documents citing a Peter Vischer responsible for selling copies of Hartmann Schedel’s World Chronicle throughout Italy in 1509 have been variably argued as the bronze founder Peter Vischer the Younger. The present author supports the theory that this is indeed the middle-son of Peter Vischer the Elder whose interests in Humanism would have encouraged his selling copies of the book to those of like-minded interests. The Vischer family knew Schedel and were themselves involved in printing woodcuts during the 1480s and remained connected with friends who likewise worked in this industry. For details concerning the sale of Schedel’s books in Italy see Andrew Pettegree (2010): The Book in the Renaissance. Yale University Press, pp. 77-78. For the production of early woodcuts by Peter Vischer the Elder see Betty Schlothan (2013): Intriguing Relationships: An Exploration of Early Modern German Prints of Relic Displays and Reliquaries. PhD thesis. University of California.

23 M. Riddick (2020): op. cit. (note 19).

24 Benjamin Ravid (2017): Venice and its Minorities in Printed_Matter – Centro Primo Levi Online Monthly. Primolevicenter.org (accessed January 2024).

25 Erwin Panofsky (1955): The Life and Art of Albrecht Durer. Princeton. See also Kristina Herrmann Fiore (ed.) (2007): Dürer e l’Italia. Exh. Cat., Rome, Scuderie del Quirinale, 10 March-10 June 2007. Electa, Milan.

26 Cecil Headlam (1901): Peter Vischer. London

27 Beate Böckem (2016): Jacopo de’ Barbari: Künstlerschaft und Hofkultur um 1500. Vienna, pp. 200-05.

28 Luciano Rognini (1975): Galeazzo e Girolamo Mondella, artisti del Rinascimento veronese in Atti e Memorie della Accademia di Agricultura, Scienze, e Lettere di Verona, series 6, vol. 25, pp. 95-119.

29 D. Lewis (1989): op. cit. (note 3).

30 It might be speculated that Hermann brought some of Moderno’s inventions back with him to Nuremberg. For example, the related DVBIA FORTVNA battle composition appears on the bronze shield accompanying the large bronze figure of Maria Bianca Sforza for the cenotaph of the Holy Roman Emperor, Maximillian I at Hofkirche in Innsbruck. The statue was modeled in 1512 by Gilg Sesselschreiber and his workshop. The Vischer’s were also involved in this project and produced the bronze figures of King Arthur and Theodoric the Great, both prevalent with Italianate influences. Vinzenz Oberhammer (1935): Die Bronzestandbilder des Maximiliangrabes in Hofkirche zu Innsbruck. Innsbruck, pp. 145-49. Moderno’s Entombment and his busts of Medusa are reproduced on the graveplate of Cardinal Albrecht von Brandenburg in 1540, cast in Frankfurt by Konrad Gobel. The youngest Vischer son, Hans, was involved in preparing Albrecht’s memorial. Cecil Headlam (1906): The bronze founders of Nuremberg: Peter Vischer and his family. London, pp. 122-23.

31 Jeffrey Chipps Smith (1983): Art and the Rise of Humanism in Nuremberg, a Renaissance City, 1500-1618. University of Texas Press, pp. 39-44.

32 Preserved in the Goethe National Museum in Weimar, Germany.

33 For various arguments concerning the authorship of the medals see Georg Seeger (1897): Peter Vischer der jüngere: Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der Erzgiesserfamilie Vischer. E.A. Seemann, Leipzig, pp. 6-13, 142; Georg Habich (1929): Die deutschen Schaumünzen des XVI. Jahrhunderts, Volumes 1-2. F. Bruckmann, vol. 1, nos.1-3, p. 3; Max Bernhart (1936): Kunst und Künstler der Nürnberger Schaumünze des 16. Jahrhunderts. Mitteilungen der Bayerischen Numismatischen Gesellschaf, vol. 54, nos. 67, 70, pp. 1-61; Klaus Pechstein (1962): Beiträge zur Geshichte der Vischerhütte in Nürnberg. Ph.D. dissertation, Berlin, pp. 75-80; Heinz Stafski (1962): Der Jüngere Peter Vischer, Nuremberg, pp. 37-38; H. Maué (1986): op. cit. (note 21), nos. 187-88, p. 387; and Ulrich Pfisterer (2013): Wettstreit in Erz, Portratmedaillen der Deutschen Renaissance in Deutscher Kunstverlag, no. 59, pp. 154-55.

34 The medal was previously attributed to Hieronymus Magdeburger. See G. Habich (1929): op. cit. (note 33). For an in-depth discussion of this medal and its relationship to the Cannae medal see Papp Júlia (2019): Az 1526. Évi mohácsi csata 16–17. Századi képzőművészeti recepciója in Több mint egy csata: mohács az 1526. Évi ütközet a magyar tudományos és kulturális emlékezetben. Budapest, pp. 149-93.

35 Staatliche Museen, Berlin, fol. 2r. For a recent essay on this topic see Jeremy Warren (2014): A note on the display of plaquettes in Medieval and Renaissance Sculpture in the Ashmolean Museum, Vol. 3: Plaquettes. Ashmolean Museum Publications, UK

36 D. Lewis (1987): op. cit. (note 3).

37 For a recent discussion of this model and its probable derivation from a sculpted hardstone original see J. Warren (2014): op. cit. (note 34), no. 327, fig. 321, pp. 870-71.

38 H. Maué (1986): op. cit. (note 21), no. 202, p. 407.

Leave a comment