by Michael Riddick

Preview / download PDF in High Resolution

The revival of interest in the Classical art of gem engraving in Renaissance Italy was preceded by certain masters praised for their skills and talents in this art form. The work of several of these artists we know well, for others, only one or two secure examples of their workmanship are identified. Of particular obscurity is the name, Niccoló Avanzi, a nobleman cited by Giorgio Vasari as a Veronese engraver of gems who later practiced his craft privately in Rome during the first part of the 16th century.1

Avanzi’s activity in Verona is contemporaneous with another revered gem engraver of that city and era of whom a satisfying amount is known: Galeazzo Mondella (called Moderno). Vasari notes that both Moderno and Avanzi were teachers of the celebrated gem engraver, Matteo del Nassaro, also of Verona and later active in France.2

Avanzi’s activity in Rome certainly post-dates previous masters practicing in that city, namely Paolo Giordano and Giuliano di Scipione Amici, both of whom executed intaglio portraits of Pope Paul II during the third quarter of the 15th century.3 In the tradition of Amici, noted as a dealer and scholar of antiquities, we might find a similar aptitude in Avanzi whom Ernst Kris noted was appreciated for his knowledge of classical art and abilities as a restorer of antique gems.4

Unlike his contemporary, Moderno, of which a plethora of works are known—mostly preserved as bronze cast plaquettes—only two inventions by Avanzi are known through documentary sources, both presumed lost.

According to Vasari, Avanzi’s most celebrated work is a scene of the Nativity of Christ in lapis lazuli, described in scale as ‘three fingers in breadth’ and featuring many figures. The work was sold to Elisabetta Gonzaga, the Duchess of Urbino and great patron of the arts.5

Not well noted in literature are a series of letters exchanged between Avanzi and Elisabetta’s sister-in-law, another of the great Renaissance art patrons, Isabella d’Este, the Marchioness of Mantua.

In August of 1512 Isabella had asked Avanzi to visit her in Mantua to retouch a carved emerald of Christ at Calvary he had presumably made and sold to her. Avanzi was unable to visit her in Mantua6 so she instead had the emerald delivered to him directly.7 The following month, Avanzi completed the work and had his assistant or pupil at-that-time, Nassaro, hand deliver the retouched work to Isabella, of which she commented it being ‘ever made so beautifully.’8 We might presume here that Isabella’s acquaintance with Nassaro would later lead to her subsequent purchase of a masterful Deposition Nassaro would execute in mottled jasper.9

In the early 20th century a jasper intaglio, three-fingers wide, of the Adoration of the Magi in the Munich Numismatic Collections was first suggested as a possible work by Avanzi by Kris (fig. 01, left).10 As a result of Kris’ observations, a double-sided carnelian intaglio at the Hermitage Museum, featuring a scene of the Adoration of the Magi on one side and a cross with a Chrismon above on the other,11 was subsequently suggested also as a possible work by Avanzi (fig. 01, center).12 Serena Franzon has noted that the atypical use of the Chrismon on an early 16th century work of Italian artwork suggests the maker was referencing a late antique period artifact (fig. 01, right).13

This and the Hermitage cornelian appear indeed by the same hand, as agreed also by Franzon, but the present author notes the lack of virtuosity tantamount to the praise of Vasari and the expense of Elisabetta Gonzaga, suggesting instead these two carved gems are the work of a lesser qualified hand and not that of a noted master like Avanzi.

While these two initial objects are a cautious though interesting first attempt at recognizing Avanzi’s work there is yet another object noted at the turn-of-the-19th century which Jacopo Morelli recalled in his brief discussion of Avanzi: a cameo of Alexander the Great in the early 18th century collection of Anton Maria Zanetti,14 which seems to have been overlooked for the last two centuries in publications concerning brief biographies on the history of Renaissance glyptic artists, which chiefly opted only to recite Vasari’s comments about Avanzi.

In the catalog of Zanetti’s collection, the Alexander cameo is noted as work by Avanzi, and one that had been prized by its previous owner, the famous Venetian collector, ‘His Excellency Zaccaria Sagredo.’15 The cameo was one of thirteen gems Zanetti had acquired from Sagredo’s heirs in Venice.16 Sagredo’s collection had been formed during the 17th century and although developed perhaps a century after Avanzi’s lifetime, it could be presumed his execution of such a cameo was remembered in association with his fine reputation and workmanship.

Seemingly unbeknownst to modern scholarship, this gem might possibly survive in the Cabinet de médailles at the Bibliothèque Nationale in France (BNF) (fig. 02, right and cover).17 While Anton Francesco Gori, in cataloging Zanetti’s collection, does not mention the type of stone in which the Alexander is carved, it is perhaps not coincidental that it is executed in lapis lazuli which may have been a favored precious stone employed in Avanzi’s productions.

In the late 19th century, Vincenzo Lazari, former director of the Museo Correr, believed he had identified this cameo from Zanetti’s collection in the museum’s own inventory. The Correr cameo, also another lapis lazuli of Alexander, which Lazari believed was instead a depiction of Athena, is 6 x 4 cm in size and is set in a gold mount with the inscription, UNUS NON SUFFICIT ORBIS, on its reverse.18 However, Gabriella Tassinari recently doubts the possibility this cameo could be Zanetti’s original, noting that a quantity of homogeneous examples of this type exist and are datable to the 16th and 17th century.19 While such skepticism ought equally be applied to the BNF cameo of Alexander, it would seem the majority of these modest and later lapis lazuli productions cited by Tassinari were often weak in quality,20 like that of another lapis lazuli of Alexander, or Minerva, in the BNF collections, which she cites (fig. 03).21 Further, the 17th century enameled gold mount given to the BNF cameo would indicate a prized work of notable quality.22

It is not known when or how the Alexander cameo entered the BNF collections,23 but we might assume it could have been acquired between 1753-95 when Abbé Barthélemy was actively curating the collection that would develop into the Cabinet de médailles at the BNF.24 For example, in 1755 Barthélemy traveled to Italy with the intent of acquiring ancient coins for Louis XV’s collection25 and we are aware Zanetti was already actively selling objects from his collection between 1750-67.26 A cameo, once prized in the collection of Sagredo, could have made for a tantalizing acquisition.

There are several further reasons to suggest the BNF cameo is the same as that belonging to Zanetti’s collection. The profile of the cameos depicted in Zanetti’s collection appear to vary from their original gem counterparts. For example, the engraving of a cameo, once thought to depict Phocione,27 is right-facing, in agreement with its original counterpart which survives in the British Museum.28 However, the engraving of a cameo depicting Antinous,29 is right-facing, unlike the original which faces left and survives in the Getty Museum30 as well as that of a left-facing Matidia,31 whose original in a private collection, faces right.32 We may assume the same is the case with the present depiction of Alexander whose engraved representation (fig. 02, left) faces left33 while the presumed BNF original faces right.

There are apparently some sketches by Zanetti’s hand at the Museo Correr which served as a point-of-reference for the engravings in the 1750 publication of his collection, yet unobserved or located by the present author. They would certainly provide further insight into the working process for translating the images of the original gems into the engraved copies executed by anonymous assistants under his direction. Nonetheless, there are certain liberties taken with regard to the representation of the gems, notably the presence of their original mounts is omitted in lieu of a generic formula that serves to offer a consistency of representation that edifies the gems themselves rather than their individualized mounts. There are also certain discrepancies in the representation of the cameos. For example, the depiction of Phocione is set in a larger negative space, inconsistent with the original, in order to center the profile of the bust. The engraving also lacks the visceral depth-of-carving of the original whose wrinkles are significantly expressed, opting for a more classicized representation. The subject’s nose is also Romanized in a manner inconsistent with the original gem. More excessive liberties appear to have been taken with the representation of Alexander the Great in which a focale is incorporated in the foreground that runs along Alexander’s cuirass. This addition may have been with the intent to add perspectival depth to what would have otherwise translated in too flat a representation. Also lacking is any representation of the inscription: ΑΛΕΞΑΝΔΡΟΣ running along its margin, certainly referenced already in Gori’s cataloging of the gem.34 However, the inscription may have been intentionally omitted in the engraving in favor of edifying the sculptural quality of the cameo itself. The same is true of the depiction of Antinous which likewise omits the feature of a fragmentary inscription: ANT, along its lower margin. As Tassinari has already noted, while Zanetti oversaw the production of the engravings for the book, their translation in engraved form was still subject to the personal interpretation or style of the anonymous engravers charged with executing them, also taking into consideration the manner of the period.35

If the Alexander cameo is indeed a rare survival of Avanzi’s workmanship, we may presume to witness his manner translated in the work of his pupil, Nassaro. As evident in the letters between Avanzi and Isabella, we observe Nassaro was actively serving alongside Avanzi during the 1510s, a period leading up to his subsequent activity in France under the patronage of King Francis I sometime after mid-September 1515.36 An early chalcedony cameo portrait bust of Francis I (fig. 04, left), and again a later, more mature in-style, agate-onyx cameo portrait of that same king, ca. 1540, (fig. 04, right) are both considered works by Nassaro.37 Although an adequate comparison of these works against the Alexander cameo—all in such small scale—is by no means adequate evidence, we may still observe a superficial likeness among them. Most notable is their standard feature of profile portraiture in low relief featuring attire inspired by classical antiquity. Each cuirass features either the face of a winged cherub or medusa, almost naive in realization, and the faces are articulated softly with reasonable skill and volume while the ears are more simplified in their rendering.

While a firm attribution of the BNF cameo to Avanzi is speculative, it perhaps remains the closest possibility to any known surviving work by that celebrated engraver of gems.

Whereas a quantity of lost original compositions by later gem engravers like Valerio Belli, Giovanni Bernardi and Annibale Fontana are known by preserved reproductions in bronze, cast both contemporaneously and later—in the form of plaquettes—we could equally speculate if the remnant of Avanzi’s praised Nativity composition—an object whose repute and purchase by an important patron—could warrant its potential preservation in this form.

In some cases, rare outliers exist for gems known by reproductions in bronze like that of a rock crystal intaglio depicting a Sacrifice to Janus that appears on the reverse of two rare medals and is known by only a few bronze cast examples;38 or that of a cameo depicting the Entry into the Ark, formerly in the collection of Lorenzo de’ Medici;39 and that of a Roman sardonyx cameo, from the 1st century AD, portraying a draped bust of Julio-Claudian Prince reproduced as a singularly known bronze plaquette.40

One particular outlier in the scholarship of plaquettes could be an Adoration of the Shepherds (fig. 05), precisely three-fingers in breadth, and while not a Nativity scene, as described by Vasari, could have been a pendant work unless Vasari misidentified the subject.41 The notion that Avanzi’s works could have been preserved in bronze is not far removed when considering his Veronese peer, Moderno, regularly and serially reproduced his own compositions in bronze.42 There are certain characteristics of this Adoration scene that suggest the hand of a cameo portrait carver, notably the feature of all characters in profile save for the child Christ who is depicted in a three-quarters perspective, perhaps to draw attention to his primary role in the scene.

Charles Fortnum was the first scholar to discuss the Adoration plaquette, originally believing it to be a Florentine work from the second-half of the 15th century43 and later adjusting his calculation to an attribution with Belli, ca. 1500-20,44 following after Emilé Molinier’s assessment of the relief.45 Wilhelm von Bode next assigned the relief to Bernardi,46 a notion subsequently followed in plaquette literature, with exception of Ulrich Middeldorf who—while accepting the attribution—noted its design was perhaps too antiquated for Bernardi.47 In most current literature, Jeremy Warren, with caution, has cited this relief as ‘probably by’ Bernardi.48

Bertrand Jestaz and Douglas Lewis have separately noted the composition was probably not by Belli or Bernardi.49 Not noted in published literature is Lewis’ condemnation of the relief as a possible pastiche from the first half of the 18th century although certain evidently old and later debased versions of the plaquette seem to counter this notion.50 Jestaz, however, suggested it was possibly made by an early follower of Belli influenced by Perugino or Pinturicchio.51 Jestaz’s reconciliation to an artist near to Belli was motivated by its similarities with Belli’s plaquette of the same subject,52 although Valentino Donati has alternatively pointed out a singular work by Bernardi that is likewise similar,53 in addition to a carved rock crystal of the Adoration commissioned by Cardinal Ludovico II Torres for the Chapel of San Castrense executed by Muzio Zagaroli, once a pupil and collaborator of Bernardi’s (fig. 06).54 Contrarily, it is reasonable to suggest Avanzi’s presumed composition—noted already by Middeldorf as too antiquated for Bernardi’s oeuvre—might instead be an altogether earlier work than any of these comparable examples and perhaps even serving as potential inspiration for these later works cited by Donati.

The present author follows Jestaz and Lewis in dissuading an attribution of this plaquette to Belli or Bernardi and it is not the first time this author has relocated a long-standing attribution to Bernardi in regard to another plaquette of the Adoration which was evidently executed instead by Matthuas Wallbaum of Germany.55

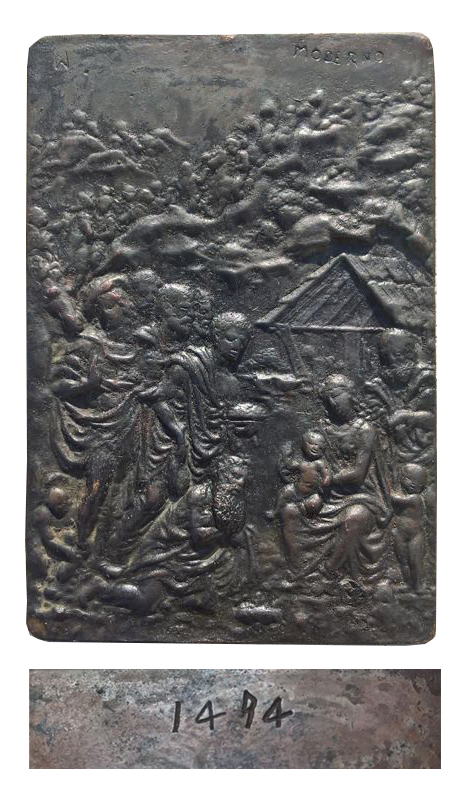

A comparable point-of-reference for the present composition could be Avanzi’s Veronese peer, Moderno, whose probably earlier Adoration of the Shepherds (fig. 07, left) has been assessed as realized during the 1490s.56 A possible terminus ante quem for Moderno’s composition could be further suggested by an example of the plaquette57 —not yet noted in literature—which features the name “Moderno,” and the letter “M” in the upper register of the relief, along with the date, 1494, on its reverse (fig. 08).58 These additions appear to have been made in the original wax model, albeit taken from an already weakened cast. The quality of the bronze, perhaps closer to bell metal, could suggest it was a model kept at a provincial foundry although it shouldn’t be ruled out that it’s a much later aftercast, potentially intending to appear old.

One could implicitly assume, based on Vasari’s account, that Avanzi’s celebrated work, was made sometime after Moderno’s suite of religious plaquettes and likewise made while he was still active in Verona sometime just before his subsequent activity in Rome, probably right around 1500.59

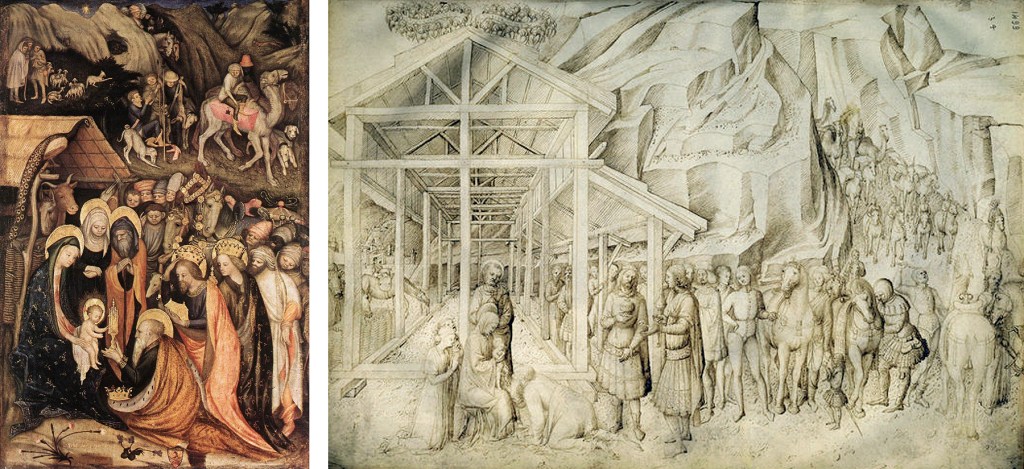

Moderno’s Adoration and the Adoration here suggested as possibly by Avanzi, both appear influenced by the strata of Veronese art during the 15th century. For example, Stefano da Verona’s Adoration of the Magi, painted in 1434, influences these compositions with a late Gothic sentiment (fig. 09, left).60 Another close source for these compositions is a sketch for the Adoration of the Magi by Jacopo Bellini (fig. 09, right).61 A possible further variation on this subject by Bellini may also have provided additional references like those from late a series of lost paintings he made on biblical themes, realized in 1465 for the Scuola Grande di San Giovanni Evangelista and in 1466 for the Scuola di San Marco in Venice.62 However, insofar as Moderno’s composition is concerned, the present author also suggests a more immediate influence in Liberale da Verona’s Adoration of the Magi at the Cattedrale di Santa Maria Matricolare in Verona whose crowded composition and figural approach appears to inform the intensity of Moderno’s version of the subject (fig. 07, right).

As regards the Adoration here proposed as possibly Avanzi’s invention, an influence from Altichiero da Zevio’s late 14th century representation of the subject appears to be a potential influence (fig. 10, left).63

Both artists include in their compositions, the African king, dubbed Balthazar, who began appearing in Renaissance art during the last quarter of the 15th century. One such crowned king is featured in Girolamo da Santacroce’s later Adoration of the Three Kings, ca. 1525-30, being not far removed from Avanzi’s presumed invention, and similarly portraying a prostrate elder king and similarly characterized child Christ (fig. 10, right).

Beyond the suggestion of a Veronese origin for the Adoration plaquette, there is also evidence for the intended serial reproduction of the composition which is observed in two incuse matrices of the relief preserved in the Museo Bottacin64 and at the Museo Correr in Venice (fig. 11),65 66 albeit in rectangular form. It is doubtful these were used for making further bronze casts, as noted by Lewis,67 and no rectangular casts are known to have survived that would have used either of these moulds as their master.68 Alternatively, they may have been used to produce examples in cartapesta or stucco, for setting into frames and employed for purposes of private devotion. All such possible examples appear to be lost-to-time. However, such rarities do exist, known by the preservation of two additionally rare plaquettes of the 15th century that are known to have been reproduced this way.69

Notably, however, a very fine blue glass example of the composition uniquely survives at the National Gallery of Art (NGA) (fig. 12). The object’s age is questionable but it remains not without reason that a colored blue glass example could have been made at the end of the Quattrocento, not unlike how Donatello’s Chellini Madonna bronze matrix, ca. 1450,70 was employed for casting glass reproductions of the relief (fig. 13).71 Such a survival would be incredibly scarce although Charles Avery and Anthony Radcliffe have previously brought attention to a rare blue glass example of a Riccio plaquette that seems to have survived.72

Verona’s day-long journey to Murano may have prompted an artist like Avanzi, who, in passing through Padua, could have encountered glass cast examples of Donatello’s composition. If the NGA example is a modern production, it poses a challenge on account if it’s remarkable fidelity, which would indicate its facture from a contemporary or perfect cast or mould of the relief, none of which appear to have survived.73 In fact, the use of dark blue glass may have been intended to imitate lapis lazuli.

Unfortunately, while this entire analysis on Avanzi’s production can only remain speculative, it is the hope of the present author that such an assessment may be impetus for future analysis of other works in carved stone which may one day come to light and to help bring awareness to one of the great intagliatori of their time, and one whom Vasari notes, ‘executed cameos, cornelians and other stones taken to various Princes.’74

With thanks to Hadrien J. Rambach for his feedback and references.

Endnotes:

1 Giorgio Vasari (1568): Lives of the most Eminent Painters Sculptors and Architects. Vol. 06 (of 10), Fra Giocondo to Niccolo Soggi. Translated by Gaston du C. De Vere, 1913. Macmillan and co. ld. & the Medici Society, London, pp. 79-80. See also Pellegrino Antonio Orlandi (1704): Abcedario pittorico nel quale compendiosamente sono descritte le patrie, i maestri, ed i tempi, ne’ quali fiorirono circa quattro mila professori di pittura, di scultura, e d’architettura diviso in tre parti… Bologna, p. 293.

2 G. Vasari (1568): op. cit. (note 1).

3 For Giordano’s sardonyx intaglio of Pope Paul II see Andrea Pietro Giulanelli (1753): Memorie degli intagliatori moderni in pietre dure, cammei, e gioje dal secolo XV. fino al secolo XVIII, p. 126; and for Amici’s carnelian intaglio of Pope Paul II see Riccardo Gennaioli (2012): Gems of the Medici. Florence, p. 34.

4 Ernst Kris (1929): Meister und Meisterwerke der Steinschneidekunst in der italienischen Renaissance. Anton Schroll & Company, vol. 1, p. 45.

5 G. Vasari (1568): op. cit. (note 1). See also P. Orlandi (1704): op. cit. (note 1).

6 Archivio di Stato di Mantova, b.2996, l. 30 – Mantova, 6 August 1512 (c. 28v.)

7 Archivio di Stato di Mantova, b.2996, l. 30 – Mantova, 19 August 1512 (c. 36v.)

8 Archivio di Stato di Mantova, b.2996, l. 30 – Mantova, 3 September 1512 (c. 43v.). Isabella calls upon Avanzi again in June of 1515 to retouch a damage on this emerald to Christ’s nose. See Archivio di Stato di Mantova, b.2996, l. 32 – Mantova, 9 June 1515 (c. 8r.) and the work is presumably completed, perhaps noted in an undelivered letter in preparation the following month. See Archivio di Stato di Mantova, b.2996, l. 32 –Porto, 31 July 1515 (c. 16v.).

9 G. Vasari (1568): op. cit. (note 1). It could be deduced that the jasper Deposition Nassaro sold to Isabella was perhaps executed ca. 1512-15, during the period just before he left for France to serve Francis I and his court.

10 E. Kris (1929): op. cit. (note 4). See also E. Kris (1930): Notes on Renaissance Cameos and Intaglios in Metropolitan Museum Studies, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 1-13.

11 Hermitage Museum, inv. И-3654.

12 Julia Kagan and Oleg Neverov (2000): Splendeurs des collections de Cathеrinе II de Russie. Le саbinеt de pierres grаvéеs du duc d’Orleans. Centre Culturel du Panthéon, Paris, p. 206.

13 Serena Franzon (2019): Preziosità e fede. Identità religiosa e pratiche devozionali nel gioiello cinquecentesco e nelle sue rappresentazioni. PhD thesis, Universitá degli Studi di Padova, pp. 164-65.

14 Jacopo Morelli (1800): Notizia dopere di disegno nella prima meta del secolo XVI. esistenti in Padova. Cremona, Milano, Pavia, Bergamo, Crema e Venezia, scrit ta da un Anonimo. di quel tempo pubblicata e illustrata da Jacope Morelli, p. 207.

15 Anton Francesco Gori (1750): Le gemme antiche di Anton Maria Zanetti. Nella stamperia di Giambatista Albrizzi, Venezia, pp. 3-4.

16 Gabriella Tassinari (2022): Collezionisti, committenti e incisori di pietre dure a Venezia nel Settecento in Collezionisti e collezioni di antichitá e di numismatica a Venezia nel Settecento. Polymnia. Numismatica antica e medieval. Studi 15, pp. 99-211, see p. 104. With thanks to Hadrien Rambach for bringing this to my attention. For a list of the thirteen gems, inclusive of Alessandro (pl. II); Giulia di Tito (pl. XVI); Commodo (pl. XXV); Caracalla (pl. XXVI); Sileno (pl. XLII); Fauno (pl. XLV); Fauno in atto di correre (pl. XLVII); Medusa (pl. LIX); Testa della Gorgone (pl. LIX); La Vittoria (pl. LXII); Sacrificio alla salute o Hygiae (pl. LXIV); Busto di donna incognito (pl. LXXIV); Testa di donna incognita (pl. LXXV), see Antonella Bandinelli (1996): La formazione della dattilioteca di Anton Maria Zanetti (1680-1767) in Congresso Internazionale ‘Venezia, l’archeologia e l’Europa,’ in Rivista di archeologia, Suppl. 17, p. 61.

17 Ernest Babelon (1897): Catalogue des camées antiques et modernes de la Bibliothèque nationale. E. Leroux, Paris, no. 667, pl. LX, p. 310. See also Pierre Marie Anatole Chabouillet (1858): Catalogue General et Raisonne des Camees: Et Pierres Gravees de la Bibliotheque Imperiale. J. Claye, Paris, no. 516, p. 87.

18 Vincenzo Lazari (1859): Notizia delle opere d’arte e d’antichità della Raccolta Correr di Venezia. Venezia, no. 426, pp. 110-11.

19 G. Tassinari (2022): op. cit. (note 16), see pp. 111-12.

20 G. Tassinari (2010): Alcune considerazioni sulla glittica post-antica: la cosiddetta ‘produzione dei lapislazzuli’ in Rivista di Archeologia, XXXIV, pp. 67-143.

21 BNF inv. cameé 450. See also Ernst Babelon (1897): op. cit. (note 18), no. 450 p. 246.

22 Unfortunately, to the present author’s knowledge, none of the other gems in Zanetti’s collection that were purchased from Sagredo’s estate, are located, and a comparison of their mounts is not possible, assuming of course that he may have been the owner responsible for commissioning its mount.

23 Noted to the present author by way of Hadrien Rambach via his inquiry to the BNF curator, Mathilde Avisseau-Broustet (email communication, June 2023).

24 For Barthélemy’s travels see Irène Aghion (2002): Collecting antiquities in eighteenth‐century France: Louis XV and Jean‐Jacques Barthélemy in Journal of the History of Collections, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 193-203.

25 I. Aghion (2002): op. cit. (note 24).

26 Diana Scarisbrick (1987): Gem Connoisseurship – The 4th Earl of Carlisle’s Correspondence with Francesco de Ficoroni and Antonion Maria Zanetti in The Burlington Magazine, no. 1007, pp. 90-104 and George Spencer, Duke of Malborough (1870): The Marlborough Gems: Being a Collection of Works in Cameo and Intaglio Formed by George, Third Duke of Marlborough, p. xvii.

27 A. Gori (1750): op. cit. (note 15), see pl. III.

28 British Museum inv. 1899,0719.2.

29 A. Gori (1750): op. cit. (note 15), see pl. XXII.

30 Getty Museum inv. 2019.13.17.

31 A. Gori (1750): op. cit. (note 15), see pl. XIX.

32 The original is published by Tassinari in G. Tassinari (2022): op. cit. (note 16), see figure 7, p. 115, therein recognized instead as a Bust of Sabina.

33 A. Gori (1750): op. cit. (note 15), see pl. II.

34 Gori states: In numis elegantissimis in honorem Alexandri Magni cusis, quum nonnulli Antiquarii, veterumque elegantiarum cultores, non caput ciusdem Regis, sed Minervae Bellatricis non raro expressum conspexerint cum epigraphe BAΣIΛEΩΣ ΑΛΕΞΑΝΔΡΟΣ; infirmis plane rationibus, magno tamen consensu in Gemmis quoque ominum praecelltissimis, specie eiusdem Deae consilii, virtuitis, ac prudentiae. (Since quite a few antique dealers, and other lovers of ancient works, have frequently seen in the medals representing Alexander the Great, not the head of a king, but that of Minerva, expressed with the epigraph BAΣIΛEΩΣ ΑΛΕΞΑΝΔΡΟΣ; with feeble reasons, but with great agreement, thought they beheld under the image of Alexander, that of the goddess [Minerva] who presided over wisdom, valor and prudence). A. Gore (1750): op. cit. (note 15).

35 G. Tassinari (2022): op. cit. (note 16), see p. 106.

36 It is believed Nassaro entered the king’s employment in 1515, particularly after the Battle of Marignano, for which Nassaro is documented having executed a medal for the king in honor of the French victory. Giovanni Paolo De La Tour (1893): Matteo del Nassaro in Revue numismatique, XI, pp. 517-61.

37 Maxence Hermant (2015): Trésors royaux: la bibliothèque de François Ier. Blois, nos. 90, 91, p.241.

38 Sotheby’s auction, 5 December 2017, lot 74. See also Vincenzo Donati and Rossana Cassadio (2004): Bronzi e pietre dure nelle incisioni di Valerio Belli vicentino. Ferrara, nos. 3 and 224, p. 180. The present author pointed out, to the former owner of this crystal, the bronze example in the form of a sword pommel at the Bardini Museum. However, the present author disagrees with Donati’s attribution to Valerio Belli and is more inclined to think the crystal was made by an artist somewhere between Belli and Giovanni Bernardi (agreed also by Jeremy Warren, via private communication 2014).

39 British Museum, inv. 1890,0901.15.

40 For the cameo see Christie’s auction, 29 April 2019, lot 33 (former collection of Giorgio Sangiorgi). For the plaquette see Spink & Son auction, 24 January 2008, lot 8. For the discovery of this observation see John Boardman, et al. (2009): The Marlborough Gems, formerly at Blenheim Palace, Oxfordshire. London, no. 372, p. 169.

41 G. Vasari (1568): op. cit. (note 1).

42 Douglas Lewis (1989): The Plaquettes of “Moderno” and His Followers in Studies in the History of Art. Italian Plaquettes, Vol. 22. National Gallery of Art, Washington DC., pp. 105-41.

43 Ashmolean Museum archives, C.D. Fortnum (ca. 1870s-1889): Fortnum Notebook Catalog, Bronzes, no. 4.17

44 Charles D. Fortnum (1887): A Descriptive Catalogue of the Bronzes of European Origin in the South Kensington Museum. London, no. I.115.

45 Èmile Molinier (1886): Les Bronzes de la Renaissance. Les plaquettes. Paris, vol. I, no. 261, p. 192.

46 Wilhelm von Bode (1904): Beschreibung der Bildwerke der Christlichen Epochen: Die Italienischen Bronzen. Berlin, Germany: Konigliche Museen zu Berlin, no. 1192, p. 113.

47 Ulrich Middeldorf (1944): Medals and Plaquettes from the Sigmund Morgenroth Collection. Chicago, no. 313, p. 44.

48 Jeremy Warren (2014): Medieval and Renaissance Sculpture in the Ashmolean Museum, Vol. 3: Plaquettes. Ashmolean Museum Publications, UK, no. 256, pp. 791-92.

49 Douglas Lewis (2000s): The Adoration of the Magi (nos. 631 and 632, invs. 1957.14.511 and 1957.14.512) (unpublished manuscript, accessed May 2023, with thanks to Anne Halpern and Margaret Doyle, Department of Curatorial Records and Files): Systematic Catalogue of the Collections, Renaissance Plaquettes. National Gallery of Art, Washington DC. Trustees of the National Gallery of Art.

50 D. Lewis (2000s) op. cit. (note 49). Lewis argued that since the majority of casts entered collections around the turn-of-the-century, none of which can be traced before 1861, and that since this time, so few have been observed in the later 20th century art market, that such observations could indicate a possible late invention. In addition to this, he noted the lack of later debased casts so frequently encountered in compositions that were further aftercast throughout the subsequent centuries. While these observations are reasonable, this same problem can be applied to quite a number of plaquettes known by two dozen or fewer surviving examples. His better argument is in his analysis of the composition’s awkwardness compared against the conventions of the period. While somewhat convincing, there are still possibilities that exist to suggest the relief is an old invention. In particular, many of the casts do seem old and Lewis was not aware of an apparently old example of the relief, set into a pax frame, kept in a church within the Diocese of Rieti (fig.14) or an apparently old cast in the collection of Alain Edrei (Morton and Eden sale, 20 April 2023, lot 100). Two additional casts not noted in his census include an art market example (Sotheby’s auction, 24 June 1982, lot 203) and a gilt example at the Saint Louis Art Museum (inv. 226.1923, fig. 05). In appreciation of Lewis’ assessment, however, there are indeed modern casts of the composition, probably late 18th or early 19th century in facture, which incorporate a narrow stand and have not been cited in literature. One such example was formerly in the present author’s collection (fig. 15) and another has been observed in the art market. The example formerly in the present author’s collection appears to have been modified by a later, separate hand and its reverse features a modern foundry mark: BK.

51 Beltrand Jestaz (1997): Catalogo del Museo Civico di Belluno, III, Le placchette e I piccolo bronzi. Le sculture. Cornuda, no. 60, pp. 79-80. Jestaz seems to rely here on Middeldorf’s challenges with the subject, who had suggested an influence on the composition from these masters. See U. Middeldorf (1944): op. cit. (note 47).

52 See for example: John Pope-Hennessy (1965): Renaissance Bronzes from the Samuel H. Kress Collection. Reliefs, Plaquettes, Statuettes, utensils and mortars. London, no. 26, p. 13.

53 Valentino Donati (1989): Pietre Dure e Medaglie del Rinascimento – Giovanni da Castel Bolognese. Ferrara, p. 204.

54 It is worth noting here that plaquette literature has frequently stated that this pax was commissioned by Cardinal Alessandro Farnese in 1539, to be made by Giovanni Bernardi, and was completed instead by hi pupil, Muzio Zagaroli. However, this is a misreading as the pax commissioned by Alessandro was to depict a scene of the Conversion of St. Paul. Rather, the Adoration pax by Zagaroli is certainly earlier. For clarification on this matter see Francesco Liverani (1870): Maestro Giovanni Bernardi da Castelbolognese, intagliatore di gemme. Faenza, pp. 26-28 and Lisa Sciortino (2014): Et Verbum Caro Factum Est. Exhibition catalog, Museo Diocesano Monreale, 27 Nov 2013-23 Feb 2014.

55 M. Riddick (2019): Bernardi or Wallbaum? Renbronze.com (accessed June 2023).

56 D. Lewis (1989): op. cit. (note 42). This dating to the earlier 1490s is followed by Francesco Rossi (2011): La Collezione Mario Scaglia – Placchette, Vols. I-III. Lubrina Editore, Bergamo, no. V.8, pp. 176-78.

57 Pietro Oromoda auction, October 2017.

58 The letter “M” appears on several of Moderno’s plaquettes, suggestive of a kind of monogram associated with him and his workshop. D. Lewis (1989): op. cit. (note 42).

59 This notion is already implied by the order of Vasari’s comments on Avanzi. G. Vasari (1568): op. cit. (note 1).

60 Likewise noted by Pietro Cannata (1982): Rilievi e placchette del XV al XVIII secolo, Roma. Museo di Palazzo Venezia, Roma, no. 24, p. 49 and F. Rossi (2011): op. cit. (note 56), no.V.8, pp. 176-78.

61 D. Lewis (1989): op. cit. (note 42).

62 Dominique Cordellier (1996): Pisanello: Le Peintre aux sept vertus, Musée du Louvre, Paris 6 May-5 August 1996 and Museo di Castelvecchio, Verona, 7 September-9 December 1996. Reunion des Musées Nationaux, Paris, see pp. 393-95.

63 It is tempting to wonder if Jacopo Avanzi, originally from Bologna, and possibly an assistant of Altichiero, who was active in Verona and Padua, may have been an ancestor of Niccoló Avanzi.

64 Museo Bottacin, inv. 131.

65 Museo Correr inv. 349.

66 Although superficial, it is notable the two surviving matrices of the Adoration plaquette survive in museums in Venice and Padua.

67 D. Lewis (2000s): op. cit. (note 49).

68 There are, however, two squared examples of the plaquette in which the upper register is truncated. See National Gallery of Art inv. 1957.14.511 and one formerly in the collection Adalbert von Lanna (Rudolph Lepke sale, 21 March 1911, lot 273).

69 M. Riddick (2021): Donatello, the birth of Renaissance Plaquettes and their representation in the Berlin sculpture collection. Renbronze.com (accessed June 2023), see figs. 5, 6, 10 and 11.

70 Victoria & Albert Museum inv. A.1-1976.

71 Charles Avery and Anthony Radcliffe (1976): The ‘Chellini Madonna’, by Donatello in The Burlington Magazine, vol. 118, no. 879, pp. 377-87.

72 C. Avery and A. Radcliffe (1976): op. cit. (note 71), see p. 382 and their footnote 41.

73 Alison Luchs points out that a bronze matrix may not have been necessary to cast glass molds, as other materials may have suited (email, May 2023).

74 G. Vasari (1568): op. cit. (note 1).

Leave a comment